Crew 5 - Crew Reports

Contents

April 7, 2002

Commander's Logbook

Today was off-sim as we moved in the hab and became familiar with the systems. All times are MDT. We have a great crew:

0200 Arrival in Hanksville from Salt Lake City. We drove in two minivans, full to the top with gear, newly purchased supplies, and the crew of six.

0645 The alarm goes off, time to have one last very long hot shower and prepare for the short trip to MDRS. Few of us have slept soundly, for we are stilled keyed up from the evening before and full of excitement for the day's activities. The day is brilliant with achingly long clear horizons and a fresh northerly breeze.

0810 Arrival at MDRS. The crew that greets us is clean, cheerful, and eager to relay the tricks. Judith Lapierre has organized a nicely printed list of handover topics, with assigned crew members. I review it and quickly rattle off the corresponding people in my crew who will pair off for the coming hour of learning and sharing.

0930-0945 Rotation 5 departs in two vehicles, we begin to feel the peacefulness of the place.

The rest of the day is a blur of unpacking supplies, organizing computers and setting up lab and recording gear. Frank Schubert, Dewey Anderson, and Brian Enke arrive to swap in a new generator, reorganize flows and sensors in the greenhouse, and attach a greenhouse door. We have brought a 5' square projection screen and attach it just above the staterooms; we intend to use it to project our daily and evolving plan.

01500-1700 Our first meeting: We discuss Safety (a briefing and forms to fill); Mission Support communications protocol (all incoming messages about the mission must go through them first; we forward everything we receive for them to handle); our daily schedule (tentatively start the primary EVA at 1600 with dinner at 2000 merged with the debrief); chores (assignments with rotations were worked in detail); reporting (follow the previous crew's pattern, but the summary will be written by our resident journalist, David Real).

1730-1900 ATV training and more organization, refilling the generator, etc.

Our sim begins tomorrow with an extensive planning meeting. One objective of this rotation will be to plan two weeks in advance in full detail. We want to determine to what extent we can project our intentions, and to understand how and why they change from day to day. If we are on a late EVA schedule, then reports will be written the next day. So Mission Support will always be a day behind. Can we compensate by projecting more than two days in advance what we plan to do?

Bill Clancey

MDRS Rotation 5 Commander

April 8, 2002

Commander's Logbook

The previous evening we enjoyed a peaceful dinner and mostly spend the evening setting up and organizing the hab. We are too tired to watch a movie. Our bedtimes vary between 2245 and 0030.

0800-0900 The crew has rested well and smiles in conversation over breakfast.

0900-1130 Planning meeting: We extensively review our objectives, methods, and constraints, and individual plans. Planning will be a key part of this rotation. We will plan forward as much as possible, including a schedule for the day. We will forward this to mission support. We will then review and replan the next day. A single document will be edited as we proceed, allowing easy comparison of our expectations and time estimates.

One question is whether we can reach a steady state by which we are able to notify mission support reliably of our plans two or three days in advance, so they may assist us. Our reports will tend to be a day delayed because of late afternoon EVAs running until dinner. To begin the process, we ask mission support for waypoints of areas known to be always wet, occasionally wet, always dry, and windy.

The crew also begins personal logs of when they sleep, do chores, or prepare reports. This is on top of group logging of water and soap usage.

1200-1400 Lunch: getting remaining laptops on line; understanding problem with UPS generator, processing mail.

1400-1630 Greenhouse EVA in full-suit by Nancy and Vladimir to plan seedlings. Proceeded by an extensive training session for the crew. Operation completed entirely on schedule.

1630-1700 Half-hour moment to catch our breaths and debrief. This was unscheduled but necessary before launching into the next EVA.

1700-1730 The EVA crew prepares, others work on learning to transfer files, using the full panoply of methods we have brought along: Compactflash (PC) card, CD-R, USB drives, and floppies. This was not scheduled, but is necessary for reporting tonight.

1730-1930 Second EVA for the new crew (Vladimir and I had a great deal of experience on suited EVAs at FMARS). Andrea, David, and Jan go on a pedestrian EVA to measure wind in various sites for a future experiment.

1930-2000 Catching up on mission support's responses to us, and logging our 2000 dinner

Bill Clancey

MDRS Rotation 5 Commander

Day 1 Report

Life on Mars Can Be Brutal

By David Real / Belo Interactive

Lost supplies of critical medicine. Computer failures. Even unannounced alien visitors. All on four hours of sleep. And, officially, it's not even Day One yet on the Red Planet.

Five scientists and a reporter locked themselves away Monday for a two-week stay in an isolated area of Utah for a research project sponsored by NASA and the Mars Society, an organization advocating exploration of the fourth planet as soon as possible.

The goal: simulate the conditions of a restrictive encampment on the Mars surface, add some top-flight scientists from around the world, and see what happens. Perhaps problems discovered during an exercise on Earth could play a critical role in preventing a crisis in space.

"This rotation is especially interested in planning," said Dr. William J. Clancey, a NASA scientist who is commanding the mission at the Mars Desert Research Station. "Can we plan our work for several days in advance, at least, so Mission Support will have enough details to help us."

Dr. Clancey, 49, is chief scientist for Human-Centered Computing at NASA's Ames Research Center in Sunnyvale California.

During the next two weeks, his crew will bunk in an unusual two-story structure that looks like a cross between a white grain silo and a stubby Apollo space capsule. The stark, reddish terrain appears eerily similar to the Martian landscape.

The crew can emerge only in tightly controlled circumstances, wearing fabricated spacesuits and communicating via handheld radios with their fellow crew members inside their temporary home away from Earth. Talking with Mission Control during an actual mission to Mars would be pointless, when a reply from such a distance would take 10-40 minutes.

The other members of the crew on this mission are:

- Dr. Vladimir Pletser, 46, is a native of Brussels, Belgium. He is an astronaut candidate for Belgium working at the European Space Agency and is also project manager for an instrument being developed for the International Space Station.

- Dr. Nancy B. Wood, 60, an experimental scientist with a doctorate in microbiology from Rutgers University. She is interested in how microorganisms adapt to harsh environments, such as could be found on Mars.

- Jan Osburg, 30, an aerospace engineer at the Space Systems Institute in Stuttgart, Germany. His specialty is human spaceflight and design of inhabited space systems.

- David Real, 49, a journalist for Belo Interactive and a former reporter and assistant Metro editor for The Dallas Morning News. He and Dr. Clancey were roommates at Rice University in the early 1970s.

- Andrea Fori, 32, a planetary geologist and systems engineer with Lockheed Martin Space Systems Co. in Sunnyvale, Calif. She helped choose a landing site for the first NASA mission designed to bring back rocks from Mars.

The team assembled in Salt Lake City late Saturday, spent several hours and hundreds of dollars buying food and other provisions, and finally embarked on a five-hour drive to Hanksville, arriving about 2 a.m. Sunday.

After four hours of sleep, the crew boarded two vans jammed with equipment and provisions and headed toward the Hab to relieve the current crew, the fourth to make a two-week stay. Less than two hours later, Dr. Judith Lapierre, a space scientist at the University of Quebec in Hull, handed command of the Habitat to Dr. Clancey, and a new chapter had begun. It didn't begin auspiciously. A crew member discovered that one of his bags containing vital prescription medicine had been lost. Fortunately, another bag carried his backup medication.

Attempts to hook up the crew's computers to the base station were unsuccessful. By choice, there is no telephone service available, in order that the project may more closely mimic the isolation that crews will face on Mars. So the Habitat's satellite dish provides the only authorized connection to the outside world via the Internet, and computer networking is vital.

After several hours of unpacking, the crew met to learn the rules of everyday life on the station and to assign mundane chores, such as cleaning toilets and cooking dinner.

Our organizational meeting was interrupted several times by visitors who lived nearby and had learned of the Mars mission. They would be our last for the next two weeks.

The day ended shortly after midnight with an exhausted crew, and no solution to our computer problems.

The next day, however, would officially kick off the simulation. On Monday morning, the hatch would close on planet Earth and the crew would open the doors on its new mission: exploring a future on Mars.

Health & Safety Officer Reports

Jan Osburg Reporting

Safety:

Fire safety information and emergency procedures were compiled and posted on the second level. Locations of fire extinguishers and emergency egress routes were clearly marked. To prepare crewmembers for a possible evacuation using the roof hatch escape route, Nancy taught everyone how to use the "roof rope" to rappel down a vertical wall.

Health:

Procedures for medical emergencies were compiled from the HSO manual and posted near the HabComm station. No injuries or illnesses were reported.

Engineering Report

Jan Osburg Reporting

Water Systems: Water consumption in the last 24 hours: 150 l (40 gallons), which seems high considering that nobody took a shower. Potential culprits: leaks, not fully established water discipline, or (most likely) the planting/seeding of the GreenHab trays which took place today (see science and EVA reports).

Power and Fuel: The new generator, which was installed yesterday by Frank Schubert and his team, works flawlessly. The only blackout occurred when too many kitchen appliances were running (but it was worth it, our DGO - Director of Galley Operations - of the day, Vladimir, produced excellent meals!) We are currently refueling the generator in the morning before 09:00h, then in the afternoon around 16:00h, and finally before going to bed, around midnight. We have not run out of fuel yet, so this schedule seems to work.

EVA Equipment (including ATVs and PEV): Yesterday, we also received three brand new ATVs, on loan from sponsor Kawasaki. They run great, and we are looking forward to many exciting motorized EVAs. Lamont took the three old ATVs back. Today's EVAs went fine, but some recommendations were already issued:

- The Platypus water bags and associated hoses should be replaced every month or so to mitigate potential hygiene problems. Spares should be stored at the hab.

- The mouthpieces should be disinfected before a new crew uses them (by immersion in Ethanol?).

- Each crewmember should have a "personal" helmet assigned to him/her during a rotation, to assure maintenance and reduce hygiene concerns.

- Small topo maps of the area with superimposed lat/lon or UTM coordinate grid, laminated and mounted on a board, would help with navigation and documentation of EVA traverses.

Safety: No Data Received

Computers and Communications: A UPS was installed to assure HabComm power supply during generator failures/refueling. Testing revealed some problems which will have to be fixed before the UPS can be considered operational. Most crewmembers' computers were successfully connected to the MDRS LAN. The Net2Phone link to the Flight Surgeon was successfully tested.

General Maintenance & Waste Management: Biolet seems to be working properly, however it is clearly operating on the edge of its capacity. Recommendation for subsequent hab designs: provide two Biolets to a) provide a backup in case one breaks down, and b) reduce continuous load by half, which should result in significantly less olfactory impact.

GreenHab: No Data Received

Geology Report

Andrea Fori Reporting

The Rotation #5 geology study plan was discussed with the team in the morning meeting. During this rotation, we intend to accomplish two goals.

Goal 1: As the last formal crew of the first MDRS season we will broadly assess the geological achievements and process used by the last four crews. This information, synthesized into a series of reports over the course of our two weeks here, will describe the information from two perspectives a) From the perspective of the Earthbound scientist. Assuming that an Earthbound scientist would have only access to the information posted on the web, I'm going to look at ways posted info can be better communicated so that scientists can use the info being sent back from the red planet. b) From the perspective of the in-person view. As a traveler who arrives at Mars after others have begun research, I need to determine if I can decipher notes and gain an understanding of the local geology, reproduce EVA's, figure out where samples are from, etc. The team will be conducting EVAs during this portion of the study to verify our findings. Weaving in what I believe Earth-bound scientist would want to know, from the perspective of planetary geologists, astrogeologists and geo-engineers I'll make suggested improvements for how and what information is recorded and relayed.

Goal 2: Create an overall geological primer of the area so that a non-geologist staff crew member can gain a basic understanding of the local geology.

EVA 61 Report

18:20-19:18 - Duration: 3:18-4:36

Objective: To plant seeds in both rock wool cubes and potting soil to set up GreenHab experiment.

Personnel: Vladimir Pletser, Nancy Wood in full suit; Bill Clancey in helmet only to photograph.

Methods:

Experimental test to compare four rapidly sprouting seed types (alfalfa, arugula, radish, and tatsoi) planted in both rockwool and potting soil. Both will be kept damp with the same circulated Greenhab water preparation. Seeds in potting soil will be kept moist manually. Germination times will be observed and compared, as well as relative growth rates. Observations will be carried out by all crew members; those on EVA will do it in full suit, while maintenance and measurements will be done by VP and NW and others simulating the proposed "virtual tunnel".

Lessons Learned:

We prepared for this by setting up a procedure for planting single seeds (which varied in size), since this is very difficult to do with the suit gloves on. It was still difficult and time-consuming, and sometimes more than one seed was deposited. It would be helpful to have a small workspace in the GreenHab.

EVA 62 Report

18:20-19:18

Objective(s) The intent of this EVA was to search for a windy and dusty location for Nancy's "Transportation of bio materials via wind" study to be set up during a future EVA. This EVA was also an introductory, brief pedestrian, familiarization exercise for the three participants.

Accomplishments

We identified three locations for Nancy to install her sample collection stations. The locations are local, open, high spots where it appears likely that relatively high amount of dirt would become airborne. We recorded GPS coordinates and maximum wind speed that occurred during a 10-second period (see map).

Lessons Learned/Misc. Notes

Some adjustments need to be made to the suits for more a more proper fit. Dave's headset became disconnected and he was not able to participate in Capcom communications. Communications originating from Capcom were often relatively loud and muddled - suggestion was made to speak in a normal tone and 30-60 cm away from the wall-mounted unit.

April 9, 2002

Commander's Logbook

Dr. Bill Clancey Reporting

The previous evening we worked on reports after dinner until about 2230, then we reviewed my DVD compilation, "Best of Devon 2001," consisting of artistic and humorous videos from my stay in FMARS and the Haughton-Mars base camp last July.

0910-1010 Planning meeting. We are picking up speed, as our plans evolve from initial thoughts to a series of steps and follow-ups. We are still not looking ahead beyond the present day, but focusing on immediate, pressing needs.

1010-1300 Individual work: Reporting, reviewing previous crew's reports, handling visitor requests (not allowed, this is a simulation of a crew on Mars), and a variety of personal tasks, such as medications review and reading a geology primer of the region.

1300-1415 An unexpectedly formal, long, and delightful lunch prepared by today's Director of Galley Operations, David Real. We sit and talk about a recent astrobiology press release and what could be learned about publishing information about scientific work before it is has been peer-reviewed.

1430-1500 Andrea Fori, our resident geologist/engineer, presented an introduction to geology and regional formations. The crew finds this fascinating and useful.

1600-1730 A lengthy EVA preparation, including equipment cleaning, testing, and suiting up.

1730-1915 A mobile (ATV) EVA to seek wet areas for soil sampling. This will be reported in detail separately.

1915-2030 Cleanup and email. Reading my email and reporting is taking at least a fourth of my time.

2030 dinner is announced-- Mexican-Martian Treat with Martian "Eggs" over Pineapple (it's a Martian yoke, get it?)

Bill Clancey

MDRS Rotation 5 Commander

Health & Safety Officer Reports

Jan Osburg Reporting

Safety:

Some fuel spilled during generator tank refueling. Lesson learned: always watch the tank level during refueling!

Also, trash bags stored in rear airlock were found to block easy egress (escape route).

A fire drill was held after dinner. The HSO activated a fire alarm on the first level and announced that the Biolet was on fire. Crew response was well coordinated, following the fire procedures posted yesterday. The commander and a crewmember "fought" the simulated fire using handheld extinguishers while the rest of the crew was ordered to evacuate. After the "fire" was extinguished, a debriefing resulted in various updates of the fire procedures. Recommendation: six disposable emergency smoke hoods (e.g. Evac-U8 brand) should be kept on the upper floor to permit crewmembers to escape down the main ladder in spite of smoke, thus giving them a better chance of controlling fires on the first level and avoiding use of alternate evacuation routes (window/ladder, roof hatch). HSO will also investigate possible use of potable water tank/pump and additional hoses for firefighting.

Health:

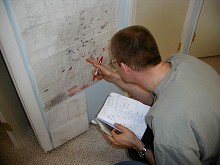

Inventoried and reorganized the MDRS first aid kit. Most items were present in sufficient quantities; some were added by HSO.

The first aid supplies were arranged into seven components:

- A general-purpose first aid case

- A small first aid kit to be taken on EVAs (stored in main airlock)

- A case with first aid material for eye injuries

- A box with non-prescription medications

- A lockbox with prescription medications (to be released by order of Flight Surgeon only)

- A box with miscellaneous bulky first aid equipment (cervical collars, books, …)

- A box with additional consumables, mainly extra bandaging material, for refilling the other first aid kits

Medical incidents:

- Two band-aids and Neosporin were issued for treatment of a minor skin abrasion

- The DGO (Director of Galley Operations, i.e. cook) touched a hot onion and suffered a first-degree burn on a knuckle (first aid measure: application of cool water for 5 minutes).

Engineering Report

Jan Osburg Reporting

Water Systems: Water consumption in the last 24 hours: 130 l (34 gallons). Recommendation: it would be nice to have a water meter in the potable water line, to get more accurate water use figures. Currently, water use is measured by reading the water level of the tank using a handwritten, external scale on the tank.

Power and Fuel: Generator fuel is running low, available supplies will last until tomorrow (Wednesday) afternoon. Mission Control was contacted to arrange for resupply through local support.

Recommendation for future generators: get one with a large built-in tank so only one refill per day (or even less) is required.

EVA Equipment (including ATVs and PEV): GPS units for EVA use were set to the required coordinate system (UTM, NAD 27 datum) so waypoints can be directly plotted onto the USGS topo map in the hab, and recorded on the EVA database spreadsheet on Habcom.

EVA communications broke down during todays EVA due to problems with the radios. Recommendation: acquire ruggedized, easy-to-operate handheld radios that can be operated with EVA gloves on (and by relatively inexperienced personnel). These are available for FRS frequencies, so the repeater and the Habcomm base station can still be used. Also regarding the radios, a portable/wireless headset for the Habcomm operator would be nice so he/she could walk around the hab while still being "on-call" for EVA requests. And, finally, the PTT button for the radios should be replaced by a VOX circuit (that activates the emitter whenever the microphone picks up sound above a certain - adjustable - level).

Safety: (see "Health and Safety Report")

Computers and Communications: Nothing to report.

General Maintenance & Waste Management: The "composting material" bucket for the Biolet is slowly being emptied; resupply is required soon.

GreenHab: (see "Biology" report)

Geology Report

Andrea Fori Reporting

We tried to reach a previously recorded waypoint today (see EVA #63 report). The intent of this exercise was to become comfortable with the Because the terrain is so varied, it was impossible to find the waypoint without destroying a fair amount of vegetation. It's obvious that the route that was taken to reach a waypoint should be recorded as well as the waypoint for future reference. Work continues on generally assessing achievements and processes.

EVA 63 Report

18:20-19:18 - Bill Clancey, Andrea Fori & Nancy Wood

Objective(s) To obtain sample for setup of ecosystem columns; attempt to revisit Waypoint 86, known to be usually wet.

Accomplishments

We departed on ATVs in the direction of Waypoint 86. Since the attempted route was impractical and a thunderstorm was visible nearby, we returned by the same route. Three vials of red-brown soil were collected at the confluence of two obvious dry rivulets to provide a sample of "intermittently wet" material. This site is now designated Waypoint 108, coordinates 5 18 180E, 42 50 504N

After returning the ATVs to the Hab, we proceeded a short distance to rock outcroppings obviously subjected to storm drainage and which were covered with ochre-colored microbial material. A small pebble covered with this growth was collected for biology experimentation. Waypoint information on this site will follow.

Lessons Learned/Misc. Notes

Samples required for biology projects were collected successfully. Route finding to previously established waypoints is nontrivial and requires advance planning.

April 10, 2002

Commander's Logbook

Dr. Bill Clancey Reporting

We were all tired again last night, so we skipped the movie session. But as usual some of the crew were writing reports past midnight and even until 0200.

0345 Traversing to the toilet, I discover I've left the time lapse video running. It's a serendipitous, for now we have a record of when everyone went to bed. The time lapse for the 20 hours or so I have captured (one 320x240 pixel frame every 3 seconds) is about 750 MB. I turn it off before returning to my stateroom.

0715 I awaken at almost the same time each day. Whatever bug I might have picked up over the weekend appears to have passed; I feel almost rested. However, everyone else is sleeping later today. I turn on the hot water heater and wait 45 minutes, using the time to bring back our internet connection. It proves difficult, so finally I decide to take a shower. A previous crew had reported it's not warm; I say it's not cold. There's always a temptation for me to tell the crew, "If you were at FMARS on Devon Island, you'd see..." For starters, the upper deck is always at least 20C in the morning, a rare temperature during July in FMARS.

I record the temperatures for the past 24 hours:

Maximum outside 27.8 C (82 F); Maximum inside 25.6 C (78.1 F)

Minimum outside 10.8 C (51.4 F); Minimum inside 18.4 C (65.1 F)

0815 The crew is stirring; I turn to my email so I can review mission support's responses during our morning meeting.

0910 Morning Planning Meeting: Most of the crew are still eating, but we launch into the meeting. I want to reinforce this regular schedule and begin by promising we will hold to an hour, as we do. I save and rename the previous day's plan, review the important new items (our communications protocol, a new task for the Engineer--to charge and test the suit radios and backpacks, and our need for fuel before nightfall). We review the action items from yesterday, reminding people of open tasks. We then formally go through each person's plan for the day. Afterwards, I forward this plan to Mission Support so they can track our activities and intentions.

A key activity today will be to prepare an EVA plan for the remainder of the mission, including at least one EVA/day. We decide to base this on Nancy Wood's soil sampling and my interest in creating an illustrated geology primer. It develops that our key problem is separating the prevous rotation's records ("waypoints") into those useful for finding routes and those that mark places of interest. Yesterday, we found that it is difficult to go back to waypoints because most do not have routes indicated. We ask mission support for help. They have sent an updated list of candidate waypoints for us to examine, but it is empty (probably just a shortcut). Reporting this problem becomes another task on my to do list.

We record the basic schedule for the day on a simple pad, so we can compare our plans to what happens.

1010-1300 Individual work. Vladimir and Nancy are learning about the Ecologger for the greenhouse. They follow Gus Frederick's tutorial and set up the program. Andrea is still struggling with a PC that has locked her out, but she uses the hab computer to review previous records. Jan gets busy with the radios. David interviews Andrea. I am busy with email and chores, finding only 10 minutes to talk to Andrea about our EVA plan--nearly 1.5 hours late and a sliver of needs to be done.

1300-1350 We enjoy an informal lunch together. This is a key moment to take a breath and sit back. We have been buzzing around the hab all morning, and this will continue for at least another six hours into the evening. This time to regroup keeps us going.

1350-1420 Individuals scramble in ways that are difficult to track--for I use these few moments to take a nap. (The time lapse video will later help me reconstruct what everyone else was doing.)

1420-1445 Jan gives a very clear, basic introduction to the GPS system, how to use these devices, and how they relate to the maps left behind in the hab. We must be careful especially to recognize when a position lock has occurred (difficult to see with the helmet), so we can record new waypoints.

1445-1625 I'm back with email for the third time today, handling press requests. We explain that a closed simulation is like Mars--no visitors. We will be the first MDRS rotation to be truly isolated, save for periodic fuel and water resupply visits from Lamont Ekker, our vital link to Hanskville, Earth.

1625-1810 I prepare dinner: A rich vegetarian tomato sauce, spaghettini, and bean salad. I also wash the day's dishes. We've learned that astronauts are using wet towels for some clean up on the International Space Station. Will MDRS provide lessons that ISS cannot, given that we have gravity here and can wash dishes normally in a sink?

1810-1910 I rearrange the stereo speakers for our movie tonight (we need an RCA jack extension), take photos of Nancy working in the lab, and coordinate with David the publishing of photos on the web. Packaging 10 photos has taken me over an hour today, including downloading from the camera, backup, cataloging, selecting the best from 240 photos, and writing captions. The first two attempts to send these photos fails from the network problems.

1910-1948 I write this report. Including this time, I've spent at least 5 hours at my laptop processing email or writing today. This is surely a big activity for all of us--and those not actively using a laptop are often trying to get it to work (e.g., David spent about an hour adjusting his PC to recognize a USB flash drive).

1950-2000 Out on the rocky plains, among the rounded hills of our Morrison Formation setting, the EVA crew of Andrea and Vladimir has reported back some interesting route-finding, which they will report separately. (Our EVA and science reports, as well as photos, will be posted when we have time to prepare the materials, usually within two days.) We ask them to return as it is getting dark and dinner is ready.

Bill Clancey

MDRS Rotation 5 Commander

Health & Safety Officer Reports

Jan Osburg Reporting

Safety:

An additional fire extinguisher was discovered in the EVA prep room next to the main airlock. It was checked and its position marked.

A smoke detector previously mounted on the side of the main stairs was removed, as there is already a smoke detector in the stairwell. It was remounted on the third level, near the roof hatch, as this is where all smoke from the hab will rise to.

In the evening, as a thunderstorm was passing over the hab, lightning occurred in the vicinity. The question arose whether the hab had sufficient lightning protection; the answer is being awaited from Mission Support.

The metal weather station pole on top of the hab was definitely not grounded, and static buildup was heard and felt that increased in intensity until we observed almost continuous sparking where the pole passed through the hab roof close to a metal roof beam. As this presented a fire hazard, the crew prepared for a rapid response to an eventual fire. After the thunderstorm passed and the static electricity generation subsided, the weather pole was grounded by connecting it to the metal roof structure using the ATV starter cables and a clamp. This is only a temporary fix, and a permanent solution has to be found.

Health:

A big ol' fly was observed escaping from the Biolet after the lid was opened. It was subsequently hunted down and brought to justice. We will have to keep an eye on the situation.

Two small insects and some minor dirt particles were discovered upon inspection of the outside potable water tank. We will have to clean it before the next refill.

No medical incidents were reported.

Engineering Report

Jan Osburg Reporting

Water Systems: Water consumption in the last 24 hours: 195 l (51 gallons), due to 5 crewmembers taking a shower in the morning.

Power and Fuel: The remaining 19 l (5 gal) fuel can was emptied into the generator tank around 10:30h this morning. Lamont came by around 19:00h and extracted more fuel from the barrel by tilting it. He will bring two full barrels tomorrow.

Generator fuel consumption: approximately one five-gallon can (19 l) every 10 hours, equaling 45 l (12 gal) per day. One barrel (55 gal) will therefore last for 4.5 days if used only for the generator. Of course, if fuel is used for ATVs, this number will be lower.

It was discovered that oil was leaking from the air filter of the generator. Investigation revealed more oil inside the air filter casing. This might be due to a recent topping-off of the generator oil, however we will observe this in case the leak continues. (Follow-up: oil does not leak while the generator is running, it only seems to leak when the generator is stopped. Strange.)

EVA Equipment (including ATVs and PEV): Radios were checked and two sets of batteries were replaced. Headsets were checked and two broken attachment clips were replaced. Headsets are now stored in individual Ziploc bags to avoid tangled wires.

Some radio settings were changed to improve performance:

- Set TX power to HIGH

- Activated key beep (every time a key is pressed, a beep sounds; this replaces the missing tactile feedback when wearing EVA gloves)

- Activated "Over" beep (this sounds every time the PTT button is released and thus saves the operator from having to say "Over" at the end of every transmission)

The present radios also have a VOX setting, but sensitivity seems not high enough for use with helmet-mounted microphones. This leaves detachable PTT keys as the best option for fatigue-free operation of PTT keys, which would also permit to keep radios protected in EVA suit pockets.

The new high power setting of the radio also allows Habcom operator to use a spare handheld radio so he/she does not have to stay close to the wall-mounted Habcom station any more.

An introductory lesson covering GPS navigation basics and operation of GPS receivers was given. A two-page GPS quick reference was created for use by EVA crew during EVAs.

Safety: (see "Health and Safety Report")

Computers and Communications: Computers: nothing to report.

Communications: see "EVA Equipment", above

General Maintenance & Waste Management: The "composting material" bucket for the Biolet was refilled from one of two big bags of composting material found near the back airlock.

Due to windspeeds of 75 km/h during gusts, the EVA team took down the MDRS flag on their way out. It was stored in the lab area on the lower floor.

GreenHab: (see "Biology" report)

Geology Report

Andrea Fori Reporting

We set out today to capture GPS coordinates where they were missing from the former EVA waypoints (see EVA #64 report) and to make another attempt at reaching waypoint #86. We were unsuccessful in reaching the waypoint thus reinforcing the necessity to record the route. We conducted a wonderful broad survey of the area and obtained more photos for the geology primer.

EVA 64 Report

18:20-19:18 - Andrea Fori & Vladimir

Objective(s) The intent of this EVA was to collect GPS coordinates with elevation for the Greenhab and the points where Nancy collected samples yesterday during EVA 63 (2 locations). This EVA was also a re-attempt to reach waypoint #86.

Accomplishments

We collected coordinates for the green hab and the first of Nancy's bio collection sites. We spent 2 hours trying to reach waypoint 86 with no success. However, we passed Candor Chasma, took photos for the geology study, got stuck on a sand dune and on the way home had a spectacular view of the hab from a nearby ridge. Just before entering the hab, we collected coordinates for Nancy's second sample collection site.

Lessons Learned/Misc. Notes

Finding a previously recorded waypoint can potentially be challenging to impossible if the route taken was not recorded. The local terrain is extremely variable and one wrong turn can result in one not being able to reach the destination.

Another lesson learned - Sand dunes approximately 3 feet high and wide are to be avoided.

April 11, 2002

Commander's Logbook

Dr. Bill Clancey Reporting

Last night during dinner, we were treated to a bizarre lightning experience. Sparks were arching from the metal weather mast (an interesting concept in itself) to the frame of the hab above the upper deck. These sparks became more insistent and louder, then finally the landscape flashed with light as a bolt struck nearby. The sparking stopped. We continued eating, and then it all started again. The storm passed before long, and we heard rain. Now we know what it is like to live inside a Faraday cage.

After I washed the dinner dishes (we are an egalitarian bunch), and after we finally forced the LCD projector to accept my laptop's video, we watched "Red Planet." Although bearing little resemblance to our situation (or what anyone might reasonably expect), we enjoy the overtones of travel to Mars and the sight of the planet (filmed in Jordan and Australia). Most of us are asleep before 0100.

0720 The hab is noticeably colder, the sky clear, and my crewmates sound asleep. It's another slow start and struggle to get my computer back on the internet, involving three of us experimenting with different cables in different places. Simply rebooting everything works, until we must turn off the power to refill the generator. And then we re-reboot.

Meanwhile, I have restarted the time lapse video, had a glass of orange juice, and recorded the temperatures:

Maximum outside 26 C (78.8 F); Maximum inside 25.6 C (78.1 F)

Minimum outside 5.6 C (42.1 F); Minimum inside 18.6 C (65.5 F)

0830 I'm finally on line and reading last night's mail from mission support. They are doing a superb job. Everything is answered and with a final summary of open items.

0905-1020 Morning Planning Meeting: We appear to be hitting our stride. The crew is volunteering multiple activities per person, and we are carrying over things from the previous day. Having recorded yesterday's plan, I can see what people said they would do, which I would have otherwise forgotten. This helps me monitor our productivity, which is becoming a topic to consider.

We are all feeling productive, but why? I ask myself, what have I done in the past day that makes me feel productive: Writing about new ideas; cataloging and selecting photographs; writing regular reports; taking good photos; everyone else being happy and productive; having the time lapse working (full day); and (somewhat oddly) having watched a movie.

What makes me feel unproductive? How about having spent two hours trying to email 10 photographs? (I repackage them to send one at a time, then I use a graphics program to cut the compressed size in half to about 200k. Still after nearly 30 hours, I have one more to force through again.)

We are all monitoring our progress. And on our fourth day it appears right to be taking stock. I resolve to ask the crew about this at dinner. Are you feeling productive? Why or why not?

1020-1300 Individual work. While trying to send those photos, I read a NASA report from June 1975, "An Optimum Organizational Structure for a Large Earth-Orbiting Multidisciplinary Space Base," by James M. Ragusa, then of JFK Space Center. Twenty-two analog social systems are compared along different work, interpersonal, and organizational parameters. The missions include Skylab, Bomber Crews, Antarctic Stations, Mental Hospital Wards, a research submarine, R&D; Laboratories, and so on. Oddly, "Exploration parties and Expeditions" doesn't make the top-10 cut, because the imagined "Space Base" would not involve traveling over a physical environment and would have a more tightly coupled interaction with a support organization. Though the conclusions would have to be reworked for a "Mars Base," the approach is broad and useful. Only two items seem especially dated, 1) the reference to values that "accept the American way of life" and 2) the mockup of a space station module, which vaguely resembles an old mainframe computer room!

1300-1430 Lunch, including a tutorial by David Real on how to help media understand what we are doing here. David has prepared a full-page handout that fascinates us. We realize two things: 1) the oversimplifications that make us cringe (e.g., the CBS Evening News title, "Mars Madness") may be helpful in getting the attention of a large audience, and 2) it is our responsibility to construct succinct, specific, and imaginative talking points. Just as one would prepare for a public talk, we need to prepare to talk to the press. We decide to work on this and have another meeting before our open house at the end of the rotation. Inspired by the discussion, I already have a new slogan, "If you liked Tang, you'll love Mars."

1430-1530 More individual work. I notice people are gravitating to favorite places. You can usually find me in my stateroom, and David also works on his laptop in his stateroom. Vladimir would prefer to do that too, but his ethernet cable is not connected. So he sits along the workstation area just next to Jan. Jan may also be working at the wardroom table, where he likes to lay out medications and medical gadgets. Or he might be anywhere, as he silently fixes and improves things all over the hab. Andrea is always seated at the hab computer, working on a comprehensive EVA plan for the next eight days. (She would apparently prefer to be using her own laptop at the workstation area. She's still locked out by a security system meant to prevent improper use of her computer, and meanwhile is unable to get the password because the powers that be are trying to page her!) Meanwhile, Nancy is happily growing things in the biology lab. She and Vladimir also work in the greenhouse. The first seeds have sprouted; Vladimir asks: seeing this, what does it mean to you?

1530-1930 We begin an interleaved double EVA, following a schedule I've posted on the wall:

EVA 65: Nancy and David, walk to windy spots to deploy a "wind catcher" (you'll have to read her report) -- 1545 suitup; 1630 egress; 1700 return.

EVA 66: David, Bill, and Vladimir to take ATVs to furthest areas to survey our domain, so we can better understand the map and past EVA reports -- 1615 suitup; 1700 egress; 1930 return.

The schedule is kept, except our egress is 30 minutes delayed by an experiment in wiring Vladimir's radio up his sleeve, so he can see it (what an idea). This works well, though next time he'll move it further from his wrist.

In considering our recent EVA experience, I realize that navigation is a fundamental problem in exploration. Historical explorers knew this very well, but few of us have first-hand experience in exploring huge tracts of new land. I need a voice in my helmet that tells me where I am relative to my (GPS-defined) destination and what direction to go. Handling paper maps or even a GPS is tedious and unnecessary. Beyond this, we need some way for routes to be found from Earth and communicated to us on Mars. This time we've stayed on the main roads and well-defined ATV trails, though I will need to study the map to know exactly where I have been.

Sighting the hab on our return at dusk, I imagine the warm and comfortable rooms inside; it sits elegantly white and sturdy, nestled in a small elbow of line of rounded orange hills, feeling like a refuge--our habitat. You know that, seeing the Mars hab on Mars itself, our future explorers will surely feel this same gratitude and pleasure.

2040 Dinner is delayed, but I'm glad to have extra time to write my report. Vladimir entertains the crew with the telescope, pointing out the sights. Nancy says, "What could possibly be better than viewing an absolutely magical sky, while somebody else is cooking dinner?" Everyone laughs.

Bill Clancey

MDRS Rotation 5 Commander

Health & Safety Officer Reports

Jan Osburg Reporting

Safety:

Using the potable water pump for firefighting was evaluated. Firefighting with this pump seems advisable in case the hab fire extinguishers have been used up and the fire is still not under control. Proposed procedure (will be tested during another fire drill tomorrow):

- During evacuation, one of the generator refill team takes the water pump from its storage place in the tools area near the rear airlock. He also takes the orange extension cord from the tool bench closet. He moves both to the outside potable water tank and immerses the suction hose of the pump into the tank.

- He proceeds to the generator and disconnects the green power cable from the generator plug panel.

- He then goes back to near the water tank and unplugs the yellow extension cord leading to the hab from the orange generator cable (plug is located approx. 3 m NW of the potable water tank). He connects the orange extension cord to the orange generator cable. Now the hab should be without electrical power, thus eliminating the risk of electric shock during subsequent firefighting.

- In the meantime, the other generator team member removes the sprinkler hose and attaches one end to the water pump outlet. She then takes the other end and gets ready to fight the fire.

- After making sure that the hab has no electrical power, the first generator team member connects the water pump cable to the other end of the orange extension cord to start the water pump. He then assists the other generator team member with firefighting. The airlocks were identified as possible "safe havens" where crew could retreat to in case of rapid decompression of hab. This requires that the airlocks are build large enough to can accommodate all crewmembers as well as their EVA suits, and still have enough remaining space to allow crewmembers to don the suits.

Health:

Another big ol' fly was observed (and killed) in the Biolet room. As an immediate measure, two pieces of duct tape were coated with a mix of molasses and honey, thus converting them into makeshift fly paper, and suspended from the ceiling in the affected area. Looks like fly season just opened...

No medical incidents were reported.

Engineering Report

Jan Osburg Reporting

Water Systems: Water consumption in the last 24 hours: 176 l (46 gallons), with one shower taken.

The water refill hose developed a bent spot where it enters the hab close to the roof due to the bending radius there being to small. This should be fixed to avoid excessive load on the water pump. Recommendation: provide a second water pump to assure hab water supply in case the main one breaks down (it seems to be operating at the limit of its specs). The water tank will be refilled by Lamont tomorrow.

Power and Fuel: Lamont brought the fuel just in time for the next refill. The hab now has more than a week's supply of generator and ATV fuel.

The generator oil leak seems small enough not to require any major repairs; we just have to keep an eye on the oil level and top it off every day.

Recommendation: TYVEK suits should be provided to generator refill team members to protect them from eventual gasoline spills, and to keep the gasoline smell/vapors away from their clothing.

Generator fuel consumption: approximately one five-gallon can (19 l) every 10 hours, equaling 45 l (12 gal) per day. One barrel (55 gal) will therefore last for 4.5 days if used only for the generator. Of course, if fuel is used for ATVs, this number will be lower.

It was discovered that oil was leaking from the air filter of the generator. Investigation revealed more oil inside the air filter casing. This might be due to a recent topping-off of the generator oil, however we will observe this in case the leak continues. (Follow-up: oil does not leak while the generator is running, it only seems to leak when the generator is stopped. Strange.)

EVA Equipment (including ATVs and PEV): Vladimir tested a new way of mounting the EVA radios to improve ergonomics: duct-taped to the lower left sleeve, with the headset wire running inside the sleeve. This is compatible with the EVA suit mirror wristband and an attached watch, making the left arm the "utiliy" arm and leaving the right free.

Recommendation: as the radios seem to require lots of batteries, rechargeable battery packs and associated chargers should be acquired, as the radios are designed to accommodate them easily.

EVA backpack 5 is down with a battery problem (switch, fuse and fans work, but the battery is dead and refuses to accept charging current). Recommendation: provide a battery charge status indicator on the EVA backpacks.

Another issue that came up during debriefing was the fact that about 30 minutes of oxygen prebreathing time would probably be required on a Mars base. To simulate this, a supply of general-purpose filter masks should be provided so EVA crew experiences realistic constraints before commencing EVA.

From today, every EVA crew will take along 20 m of strong rope for towing of ATVs and for belaying of crew during pedestrian descents, duct tape, a compass as a backup navigation aid, and a small first aid kit.

Safety: (see "Health and Safety Report")

Computers and Communications: David updated and revised the MDRS IT Manual, incorporating our lessons learned.

To connect portable computers to the hab stereo system, a long (10 m) audio cable with 3.5mm jacks is needed, along with an adapter from 3.5 mm to audio cinch (standard amplifier input). This equipment is available in all electronics stores.

Communications: see "EVA Equipment", above

General Maintenance & Waste Management: The two small general-purpose multimeters in the tools area do not work. A high-quality multimeter should be acquired (the existing Fluke 32 mentioned in one of the earlier reports is designed only for high-voltage, high-amp applications). A stock of long nails, wire, and rope in various diameters should be provided.

GreenHab: (see "Biology" report)

Geology Report

Andrea Fori reporting.

More photos for geology primer obtained. Explored area.

EVA 65 Report

Duration: 16:22-17:10 - David Real & Nancy Wood

Objective(s) Pedestrian EVA to install windblown dust collection devices at waypoint 102, which was previously established to be windy. A preliminary hole was dug before inserting the bamboo stakes on which the collection vials were mounted. The open end of the vials were facing the prevailing very light breeze.

Accomplishments

This was an easy EVA, and GPS navigation to the waypoint was straightforward.

EVA 66 Report

18:20-19:18 - Duration: 17:20-19:30

(coincidentally these are within ten minutes of EVA 63)

Personnel:

Bill Clancey (reporting), Vladimir Pletser, and David Real

Objective(s) To become oriented to major geological features around the hab; to find previously documented waypoints; and to investigate two routes Clancey had been shown during the March reconnaissance.

Accomplishments

We departed on ATVs north, in the direction of Waypoint 18, to find outcroppings noted by a previous crew. We visually identified these, but not definitively. The GPS reading was inconsistent with the previous record. We proceeded down the road towards Waypoint 15, but encountered a herd of Martian cattle on the road (named by their uncanny resemblance to Earth cattle). With the cattlemen nearby, we chose to avoid disturbing the herd and reversed course. On return, we chose an ATV trail towards the West and verified that it would bring us to the Mid-Ridge Planitia. Along the way, we noted often wet ravines and a grassy filled-in pond that might be of interest to Nancy Wood.

Passing the hab, we continued south, looking for a previously used route to the Mid-Ridge Planitia. After becoming familiar with the area, but not finding any obvious west-trending roads, we returned to the hab. A GPS reading for the turnoff would have been useful.

On return, we found that the waypoints we recorded for intersections do not correspond to the map; the cause is yet to be determined.

Lessons Learned/Misc. Notes

We confirmed the lesson of EVA 63 that route finding to previously established waypoints is nontrivial and requires advance planning. We determined that every crew member going on an EVA must be able to use a GPS. We require maps that we can mark in the field. An ideal system would provide audio directions through the helmet and enable voice commanding for waypoint setting, while driving, rather than the current tedious GPS device manipulations.

April 12, 2002

Commander's Logbook

Dr. Bill Clancey Reporting

Dinner was delayed until well past 2100, but most of us did not mind, for we had so much to do. We were treated to Jan Osburg's spicy Candor Chasma Chicken and potatoes. Afterwards, I showed my "Devon Video Shorts," ranging from the humorous (ATV stuck in a creek) to the thought-provoking (Jim Rice talking about Mars) and the sublime (a helicopter ride to Thomas Lee Inlet, with music prepared for the Grand Canyon). My stateroom light was out at 1140, which seemed too late.

0700 I sneak out of my stateroom in a towel and flip on the hot water heater.

0715 Feeling rested, I dress and egress, and this time find Nancy preparing coffee. I record the temperatures:

Maximum outside 23.4 C (74.1 F); Maximum inside 25C (77 F)

Minimum outside 11C (51.8 F); Minimum inside 17.5C (63.5 F)

I allow Nancy the first shower, and sit down to begin reading email--still an hour before I will have breakfast. Quickly enough, I get my chance to wash, and feel invigorated. This is the way to start a day, for sure, but our rationing does not allow it often. (Indeed, we are running short of water and expect to be reprovisioned today. But our supplier never shows up.)

After a quick breakfast of juice and cereal, I check the Hanksville weather--a dramatic change from the previous day: Temperatures rising to the upper 80s are forecast this weekend, with possible snow showers Tuesday and a low of 25F! I enter all of this in my mission planning table; on a whim I'm checking how forecasts change from day-to-day. Is the crew's daily planning any better or worse?

0905-1040 Morning Planning Meeting. We seem to have more to discuss than before, and feel too pressed for time to give the topics justice. Indeed, one topic is productivity. I mention to the crew that in four full days there has only been one report (Real's story) on top of the EVA reports and required reports that Jan and I write. We have agreed that daily reporting of science is not necessary, but we had also agreed that two reports would have been completed the previous day. Where is the time going?

Andrea says she needs at least 15 minutes of uninterrupted time to do anything. I point out that we have daily "individual work" time before lunch of at least two hours and often three! Vladimir explains that it's the little things that take time --email with family and colleagues (should that be more stringently controlled on Mars?), and all of the myriad details of work itself. He illustrates with the example of fetching the datalogger from the greenhouse, downloading data, determining that values are not as expected, debugging the problem, fixing the problem, and returning the datalogger to the greenhouse. One can easily spend an hour doing that, when all that was intended was to verify that a task done yesterday had succeeded. Later in the morning we observe another example: Vladimir and Andrea must refill the generator, which causes a hab power failure, which requires the internet to be rebooted, which holds up anything we were in the middle of doing online.

Despite this, when we make the rounds, everyone speaks convincingly of having felt very productive on multiple occasions in the past few days. Andrea has produced an EVA plan for the remainder of our rotation. Nancy has set up the lab to her liking and started experiments. David has written two lengthy stories. Jan has reorganized the med kits ("into logical elements"), and Vladimir has begun a variety of plant growing experiments.

We briefly consider how things might be different if mission support imposed deadlines or we were trying to communicate with colleagues who were assisting us back home. Would priorities change?

We also determine that we are spending five hours a day in group meetings and meals. We clearly like to be together. But several people are quick to volunteer that they could be content to grab something and go back to work, eating alone, as they do at home. Instead, we've made lunch into an elaborate social event, and added a tutorial session afterwards, that extends the time to two hours. We resolve to cut this back and save the next tutorial for the inclement weather. Now, if this had been a Mars mission, we would have just had six months living together on the outbound journey. We'd be looking more outwards into the land around us, than inwards into the minds of these interesting new friends we just met not even a week ago.

Further showing the need for automation, we decide we should create an audio recording to send to mission support. This adds 15 minutes to the meeting, first to explain what we are doing, and then pass the recorder around. I then ask, who will download this data and send it to mission support? We look around silently. (As I write at 2051, nobody has found time to do this.)

1040-1315 Individual work. I download, backup, catalog, and sort my photos from yesterday so I can show Andrea the geological features. As we meet (an EVA-planning subcommittee) I opine again that I would be content to have mission support give us a list of places to go, with routes, and full instructions. I can't believe I'm thinking this, when the opposite conclusion seemed so obvious to me on Devon Island in 1998: Surely the crew would want to plan their excursions themselves. At least in rotation 5's "wholistic simulation" experience, we are busy enough handling equipment and reporting, and would be happy to offload some of the planning.

Andrea and I review her plans and reorganize the EVAs, considering the weather, specific objectives for the rotation, and individual schedules (don't send the Director of Galley Operations out on a late-afternoon EVA). At the end of this exercise, I believe the planning work has really only just begun. When will we find time to do this? Would mission support on Earth tolerate our preference to plan one day at a time, each morning?

1315-1340 We have a less formal, quicker lunch. Vladimir asks if it's okay to leave the table to get back to work, the chorus says yes!

1347 Andrea announces that after nearly 5 days of waiting, she's received the information she needs to unlock her computer. She says she's felt withdrawal, not being able to see her familiar screen. She must wait a bit longer, for now she is the computer's administrator and must figure out how to restore her personal settings.

Meanwhile, David and I review our GPS units and set waypoints, so are ready for the planned EVA.

1415-1430 Nancy shows me a nicely prepared tool kit of materials, with written instructions, for retrieving her experiment apparatus on a nearby hill.

1440-1815 David, Andrea, and I go on a mobile EVA (#67) to carry out Nancy's plan. We have learned that each EVA should have a major objective, which is pursued first. The samples in the bag, we move on the secondary objective, to find a route I was shown in March, for hiking up above the Dakota formation to oyster beds of the Cretaceous period. We lack waypoint information for the turnoff, so I follow a four-wheel drive road on the map. It is too far south. Retracing our steps we eyeball the ridge, which I recognize and wind up exploring a side wash. This is very interesting and I feel good to be inspecting hidden gullies just as we do on Devon Island. Even the many rocks remind me of Devon. An ironic thought: in the very act of exploring, the memory of another place makes the new setting enjoyable.

Returning to the main road, we proceed back north, and now I spot the track and the path itself, visible not that far away. From the main road, it seems steeper than I expected, so I had ignored it on the first pass. (What really do we know about the perception of navigation?) The rest of the EVA is uneventful, as we achieve our objective. All along the way, I ask Andrea how I should interpret various colors, layers, and shapes. Driving back, I start to understand that a lay person expects every single layer to have a name, but it seems that they are only categorized broadly by type (color, content, and so on) and named by characteristic examples (e.g., The Salt Wash Member of the Morrison Formation). I have learned the basics: The layers are grouped by Member, Formation, and Period. Now what of my idea of having characteristic photos of each member? Does that make sense? Our books show drawings, but not photographs of typical rocks and features. Why not?

1815-2030 I feel overwhelmed with tasks: Write up EVA 66 from yesterday, prepare more photos for the web, write my log, review the science report. All this before dinner.

2037 David warns to save your work. The power fails and Andrea and Vladimir, the team on duty, refill the generator. In the dark upper deck of the Mars Desert Research Station, we are all hauntingly lit by our laptop screens. Jan, always at the ready, is holding a flashlight for Nancy in the galley.

Tonight is Yuri's Night, so we will celebrate with a special meal, music, and a movie.

Bill Clancey

MDRS Rotation 5 Commander

Health & Safety Officer Reports

Jan Osburg Reporting

Safety:

Nothing to report.

Health:

Biolet: see engineering report.

No medical incidents were reported.

Crew morale received a boost by celebrating Yuri's Night.

Engineering Report

Jan Osburg Reporting

Water Systems: Nothing to report, except that the outside water tank needs refilling. Water consumption in the past 24 hours: 160 l (43 gal), with two people taking showers.

Power and Fuel: Lamont brought 4 liters of oil for the generator and the ATVs.

EVA Equipment (including ATVs and PEV): Suit backpack 5 was checked and a blown fuse diagnosed. Mission Support was contacted to inquire about replacing fuse (2 A) with 2.5 A fuse.

Safety: (see "Health and Safety Report")

Computers and Communications: The battery of the existing Fluke 32 multimeter was exchanged (a 9V cell; we are out of these and need more); afterwards, it worked fine (but still for AC only). It was used to check out the new UPS, which was subsequently declared operational. The Hab computer, its monitor, and the Starband satellite terminal are now connected to its buffered output plugs, giving us 10 minutes of assured communications in case of generator failure or maintenance, and relieves us of the task of having to shutdown the computer every time the generator is refilled.

One problem with running any UPS in the hab is that anytime the generator reaches its performance limit, i.e. power demand is high, the voltage goes down to around 100 V. This seems to be the threshold for the UPS to switch from regular to battery mode. So, with the voltage oscillating around 100 V during high-load activities such as cooking, the UPS constantly changes modes, each change accompanied by a beep. This poses no short-term problem (apart from the annoying beep), but will surely ruin the UPS battery within a few weeks. Maybe this is what happened to the previous UPS.

After long e-mail conversations with her IT support, Andrea's computer was brought back to life and is now cooperating with the local MDRS network. Her productivity has already gone way up

;-)

General Maintenance & Waste Management: The Biolet was checked, as it seemed to get full. Both fluid check hoses were empty, which is nominal. The biomass in the receptacle was manually stirred (using a long stick…) to smoothen it and improve composting effectiveness. Disposable gloves were worn throughout the maintenance activity. The TYVEK suits requested yesterday would have come in handy for this task, too.

GreenHab: (see "Biology" report)

Geology Report

Andrea Fori Reporting

Another geology EVA achieved today (see EVA #67 Report). We visited the boundary between the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods and digitally recorded the transition. Just above the boundary was an expansive field of fossilized oyster shells. Had a briefly exciting encounter with some erosional features that closely resembled dinosaur vertebrae.

EVA 67 Report

EVA Scenario Overview

We had two main objectives for our EVA on Friday, April 12, 2002. The first objective was to retrieve two sample containers designed to collect wind-blown grit. The containers had been placed by an EVA team a day earlier, on Thursday, April 11. The EVA team also collected two dry samples from the same site. The second objective was to discover and document a path that would enable future explorers to visit the oyster fields that are indicative of the Cretaceous era south of the Hab. DATE: 04-12-02EVA Highlights (EVA CDR)

- We successfully retrieved Nancy's samples.

- We turned off the road in pursuit of the oyster bed at new Waypoint 109, N 4248712, E 518896

- We found faux dinosaur bones at new Waypoint 110, N 4248618. E 517873, then discovered this layer is prevalent throughout the immediate region.

- We found an oyster bed at new Waypoint 111, N 4248629, 517882

PRE EVA OPERATIONSBoth the CDR and MDRS2 took the time to familiarize themselves with the GPS equipment, one supplied by the Hab and one a personal item. Nancy Wood, the biologist in charge of the experiment to collect wind-blown grit for further analysis, fashioned a kit to expedite the timeline for the EVA team. The kit included two labeled lids for the plastic sample containers at the site, and a marked label that also served to seal the samples from contamination. A marked paper-backed label was partly peeled from its sticky backing and a pipe cleaner attached to it in order to make it easier for the EVA crew to detach the label and apply it correctly to one of the containers that had two holes pierced into its walls. Two other sample containers were also labeled so they could be identified later. Nancy prepared the instructions for the collection in advance, since she was not a part of the recovery EVA team. This may become standard for field scientists who can direct others to collect samples while they remain in the Hab to do more pressing and productive work. All three EVA members also wore mirrors on their forearms to monitor the progress of the others as a safety measure. AIRLOCK INGRESS/DEPRESS Normal ingress and depress. Radio checks completed. The EVA crew was greeted immediately be the other three crew members in celebration of Yuri's Night. HAB EVA MONITORING

| NOMINAL EVA COMM/SAFETY CHECK

(Hourly Operation) |

Comm ck

1 |

Comm ck

2 |

Comm ck

3 |

Comm ck

4 |

Comm ck

5 |

Comm ck

6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIME | 1545 | |||||

| EVA #

(If Simultaneous EVAs) |

||||||

| ATV Odometer

OUT/IN |

||||||

| REPORTED MAP LOCATION | WP 102 | |||||

| REPORTED STATUS | OK | |||||

| Auxiliary Information | Position Check |

EVA MONITORINGTerrain prevented communication between the Hab and the EVA team near the Jurassic/Cretaceous boundary. The Hab reported that voices were heard but words could not be deciphered. The EVA team also could hear some of the words from the Hab, but it was difficult to carry on communication.

POST EVA INGRESS AND CLEANUP Normal ingress and cleanup was done. EVA CREW: COMMENTS/OBSERVATIONS/LESSONS-LEARNED EVA CDR: Nothing beats being with specialists in their home turf. You have the opportunity to ask about what you see. But you learn by just watching where the specialist goes and what she looks at. Just seeing Andrea kneeling over the faux bones showed that she found these rocks interesting, too. Then she looked around for something similar, showing us by example how to interpret most any odd feature we might ever see. EVA MDRS1: It was fascinating to be able to put my finger on the boundary between two significant periods in geological history: splitting Jurassic from Cretaceous . The oyster fields seemed like such a happening place to be. There were these huge mounds of oysters, hanging out and having a great time. EVA MDRS2: I was struck by how prepared Nancy Wood was when she asked us to retrieve her dust samples from Way Point 102. She had thought of almost every contingency. The only unforeseen problem was unzipping the zip-lock bag. When Nancy learned of our troubles, though, she had a solution: Just grab the sides of the bags and pull. That would force the zippered bag open without fumbling for the top edge of the bag with bulky gloves. I was also struck by the open expanse of the oyster field, which seemed to just open up under our feet once we reached the top of the plateau. A truly incredible experience. Nearby were also interesting examples of ruby-colored quartz and some translucent ones, too.

Crew 5 Profile - Andrea Fori

By David Real / Belo Interactive

Aboard The Mars Desert Research Station, Utah - Talking about life on Mars can sometimes seem as much philosophy as science - just like life on Earth.

"We don't know what we don't know," said Andrea Fori, 32, a planetary geologist specializing in Martian geology. "That's good information."

Considering the grand scope of the physical universe -or even the internal universe that each individual carries inside - we know very little, Ms. Fori said. But it's a start, whether it's Mars or Earth.

"When you are aware that you're lacking information, you're much more informed than when you don't know what information you're missing," she said.

She is working hard to reduce that information gap by donating two weeks of her vacation to a project in the Utah desert. The Mars Desert Research Station is a project of the Mars Society, a group advocating exploration of the Red Planet as soon as possible.

A half-dozen explorers are living in an isolated station that mimics some of the living conditions and problems that astronauts could face.

Ms. Fori already has experience helping to resolve more earthly problems.

Every time a thunderstorm boils up and pictures of clouds dash across a television screen, it's a good bet that the images came from a satellite she helped to build.

As a systems engineer at Lockheed Martin Space Systems Co. in Sunnyvale, Calif., she helped to integrate the world's first weather satellite - TIROS, or Television Infrared Observation Satellite. She planned how the prorgam was handled and ensured that the requirements of the project were met throughout its design and production.

Geologists will be among the first to visit Mars, she said. That's why the experience of simulating a Martian research habitat and participating in field trips - extra-vehicular activities, or EVAs - is so important.

"We will definitely need to do geological studies in person," she said. "This exercise of living in the Hab, planning, and then putting on a suit and conducting geological studies is really practical.

"When you put on a 30-pound spacesuit and you bend over and try to pick up a rock, it's difficult. Without going through the motions of doing it, you wouldn't necessarily know that.''

She said a problem that made her computer inoperable was the biggest obstacle she faced during the simulation.

"To not have that working smoothly is extremely disruptive," she said. "It's changing my whole mind frame; I'm not able to plan; three days have gone by and I haven't gotten anything done in terms of practical EVAs; and it's just really posing a big problem in many aspects of everyday life."

However, she said she was pleasantly surprised by the camaraderie that has developed among the six crew members, despite the cramped conditions of the 4 ½-by-10-foot state rooms.

"The food and the living conditions and living on top of everybody has actually gone better than I thought it would,'' she said. "I expected it to be more difficult psychologically.

"The lack of privacy, being dirty, not having good food to eat - I thought all those things would make your mind frame skewed to thinking about those issues instead of accomplishing something on EVAs. But the domestic issues have been less of a problem."

Ms. Fori, who grew up in Coxsackie, N.Y., near Albany, said she never thought that she would study geology.

"No pet rocks," she said.

But she changed her mind during her undergraduate years at Hartwick College in Oneonta, N.Y.

"I just thought it would be really neat to learn about the Earth," she said.

Her career took another turn in 1994 when she turned to planetary geology and decided to study Mars for three years to earn her masters degree at the Mackay School of Mines at the University of Nevada at Reno.

"I was never a space buff as a kid," she said. "It came through education. I was exposed to this world of really, really exciting research that was going on."

During graduate school, she received funding from NASA to investigate the mechanics of geologic faulting on Mars, such earthquakes.

In the summer of 1997, she was one of about a dozen people selected from a nationwide search for the 10-week Astrobiology Academy at the NASA Ames Research Center in Sunnyvale, Calif.

She worked with Dr. Jack Farmer, a leading biologist/geologist, to select a landing site for the 2005 Mars mission that would pick up rocks and return them to Earth. The mission to Parana Valles, potentially rich with fossils, was postponed after the loss of two NASA Mars probes a few years ago.

In the summer of 1999, she was among 80 students worldwide chosen for a 10-week-program at the International Space University in Thailand. The students were able to talk to the heads of many space agencies around the world to come up with a strategy for exploring the solar system.

"The intent is not necessarily to come up with something spectacular," she said "The intent is to learn to work together, think through ideas, and ideas for international space agencies to consider."

She said the cultural hurdles were difficult to overcome because students from some nationalities deferred to Americans and Canadians in group discussions without offering their ideas.

Now that she is in the Utah desert, she said she welcomed the opportunity to break from her routine at Lockheed Martin and focus once more on her love for Mars and geology.

"You can get in a rut building a spacecraft, and you need to step back sometimes and say, 'All right, what's the big picture here? What, as a human race, are we working toward?' So it's kind of a reality check for big goals as a human race.

"I've had a great experience. It has been a lot of fun and it has renewed my enthusiasm for Martian exploration."

April 13, 2002

Commander's Logbook

Dr. Bill Clancey Reporting

Dinner again was after 2100, which allowed me to write yesterday's report. Our Yuri's Night repast, prepared by Nancy, was a feast: Pasta salad, beef stew, and warm fruit medley. She explained how, fitting the seven continents theme of the Night, all the ingredients had come from around the world: Sun-dried tomato from South America, bell peppers from North America, honey from Africa, olives from Europe, rice from Asia, and (perhaps) the Shiraz wine grapes originating in Australia. Jan provided an equally eclectic musical mix on his laptop, illustrated by Winamp's psychedelic and hypnotic graphics. Afterwards we settled down to watch the movie 2010, which we had carefully chosen from the hab's library. Alas! The container was empty, so we settled for "Outland," which had the virtue of being short (David asked, "When do the special effects begin?"). We toughed it out and retired for bed, exhausted. My light was out at 0115, though Vladimir and Andrea still had to refill the generator.

0700 I awake, not thoroughly rested, but it feels time. Almost... 0740 I realize I'm not going to sleep any more. An azure sky fills my portal, enticing me to start the day.

During a trip to the toilet during the night, I had seen Jan's note on the sink on the lower deck: We have only 2 gallons of water in the tank, and are to use water only for drinking and teeth brushing. I learn as others awake that the pump had broken, so the remaining 30 gallons or so in the outside tank are not accessible. (Writing reports like this, I repeatedly discover that I do not always retain incidental details: Does the tank hold 300 gallons? Is it 1.5 meters high? What kind of plastic is it? I do not have this kind of mind.)

So the day has begun off balance, with a feeling of slipping sideways, not following the course. My breakfast is delayed by new decisions (should I take the remaining milk for cereal? will we have coffee?). In the meantime, I record the temperatures:

Maximum outside 19.4C (66.9 F); Maximum inside 23.4C (74.1 F)

Minimum outside 4.2C (39.6 F); Minimum inside 16.1C (61 F)

This coldest night was welcome. The storms of yesterday have given way to a brilliantly clear day, heating up fast.

0905-1030 After breakfast, it's evident that we won't start with a meeting--we need water, so we all head outside in our civies. We've decided we should siphon the water into 2.5 gallon jugs. We try Vladimir's first idea of putting the tank on sawhorses (actually, his first idea was "seahorses"), but it is too heavy by far. So we jockey around, tossing out ideas: Roll it up the hillside? Prop it up on a ladders? Getting the tank on its side proves easy enough, and we prop it up with the ladders and rocks. What, no duct tape? (We actually look around, checking for a use for it.)

Jan has sterilized some clear tubing from the lab, and wearing his pink rubber gloves, and towering a bit over even me, in crew cut and glasses, he is quite the German engineer. We follow along.

Then a new problem: The tubing is floating to the surface and won't fill. Jan directs Andrea to get a large spoon from the galley. She returns and we attach it to the tubing end with duct tape. Voila! It works.