Difference between revisions of "Starship"

(→Characteristics of Starship: Added Version 2.) |

|||

| (31 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

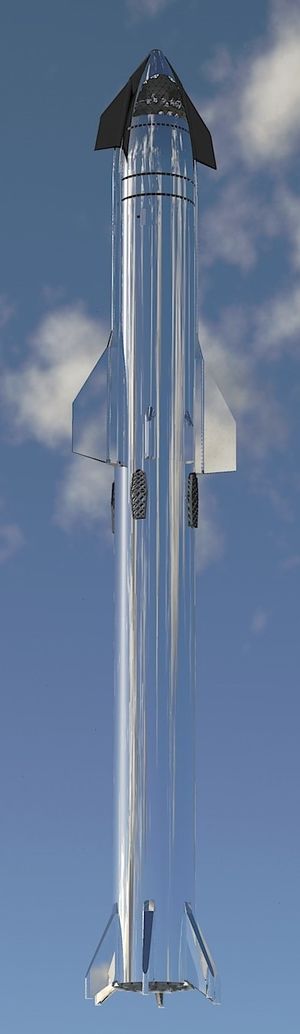

| − | [[File:Starship | + | [[File:Starship mirror2.jpg|alt=|thumb|The December 2019 Starship-Super Heavy launch stack]] |

| + | '''Starship''' is the name of the 2019 version of the second stage of the [[SpaceX]] reusable super heavy lift vehicle, resting upon the [[Booster|Super Heavy]] booster. The term "Starship" may also be used to refer to the complete stack of both stages. SpaceX’s Starship spacecraft and Super Heavy rocket (collectively referred to as Starship) represent a fully reusable transportation system designed to carry both crew and cargo to Earth orbit, the Moon, Mars and beyond. Starship will be the world’s most powerful launch vehicle ever developed, with the ability to carry in excess of 100 metric tonnes to Earth orbit. Starship will enter Mars’ atmosphere at 7.5 kilometers per second and decelerate aerodynamically. The vehicle’s heat shield is designed to withstand multiple entries, but given that the vehicle is coming into Mars' atmosphere so hot, we still expect to see some ablation of the heat shield (similar to wear and tear on a brake pad). The engineering video below simulates the physics of Mars entry for Starship.<ref>[https://www.spacex.com/vehicles/starship/]</ref> | ||

| − | + | If SpaceX is able to make this ship work, with rapid turnaround, the cost of launching a kg into Low Earth Orbit will decrease at least ten fold. This will make all space projects (including Mars missions) much cheaper. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Development history== | |

| + | ===2016 Interplanetary Transportation System=== | ||

| + | The origins of Starship are rooted in the Interplanetary Transportation System. This architecture was revealed in a 2016 speech by [[Elon Musk]] at the [[International Astronomical Congress]].<ref>Musk, Elon. 2016. ''[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H7Uyfqi_TE8 Making Humans a Multiplanetary Species]''. Guadalajara, Mexico.</ref> The concept was conceived as a two-stage spacecraft able to be reused a thousand times and to hold crews of over a hundred people with its primary intent to send people to Mars. The concept would depend upon tanker ships and orbital refueling, and it would extensively utilize [[in-situ resource utilization]] to produce the methane fuel required for the return voyage to Earth.<ref name=":0">"[http://spaceflight101.com/spx/ Interplanetary Transport System]". n.d. Spaceflight101.com. Accessed January 4, 2020.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The design was immense, with a twelve meter diameter and depended upon forty-two methane [[Raptor engine|Raptor engines]] on the booster alone, allowing it to produce thrust of thirteen-thousand metric tons. The stacked system would stretch up one-hundred-twenty-two meters into the sky. Upon stage separation, the booster would return to the launch site, landing propulsively on the launch mounts so that it could quickly be refueled and again flown. The second stage, which in some launches would include a habitat, had nine additional Raptor engines to accelerate the ship to Low Earth Orbit. In order to continue a trip to Mars, the second stage would have to be refueled by one or more tankers.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The proposal of the carbon fiber launch vehicle came with an estimated necessary cost of investment of ten billion dollars by Elon Musk, who suggested that a massive public-private partnership might be the best option for the vehicle. The original timeline of the proposal called for structures and propulsion development to be completed in 2019, when ship testing and orbital testing where to begin. Orbital testing was to be completed in late 2022, and shortly thereafter Mars flights were to begin.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Musk acknowledged that this timeline was incredibly ambitious, but he believed that it was not ''too'' unreasonable. Musk took pride in announcing that two components of the system had already been built and were undergoing testing: the twelve-meter carbon fiber tank to store oxidizer in the second stage<ref>"[https://twitter.com/spacex/status/780859793443401728?lang=en First Development Tank for Mars Ship]". 2016. Twitter. September 27, 2016.</ref><ref>Mitchell, Jacob. 2016. "[https://twitter.com/JandCandO/status/780862729204723713 Here Is the inside of This Tank for You Guys!]" Twitter. September 27, 2016. </ref> and the first development versions of the Raptor methane full-flow staged combustion engine.<ref>Musk, Elon. 2016. "[https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/780275236922994688 SpaceX Propulsion Just Achieved First Firing of the Raptor Interplanetary Transport Engine]". Twitter. September 26, 2016.</ref> Initial tests of the carbon fiber tank proved to be successful, with Musk noting that his company had not "seen any leaks or major issues" when testing the tanks with cryogenic propellent.<ref>Milberg, Evan. 2016. "[http://compositesmanufacturingmagazine.com/2016/11/spacex-successfully-tests-carbon-fiber-tank-mars-spaceship/ SpaceX Successfully Tests Carbon Fiber Tank for Mars Spaceship]". Composites Manufacturing. November 29, 2016.</ref> After heavy testing, the tank was destroyed in February 2017.<ref>"[https://www.reddit.com/r/spacex/comments/5ul1du/remains_of_the_its_composite_tank_in_anacortes_wa/ Remains of the ITS Composite Tank in Anacortes, WA]". 2017. r/SpaceXLounge on Reddit. February 17, 2017. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===2017 Big Falcon Rocket=== | ||

| + | Over the course of a year, Musk and SpaceX recognized that a smaller, more feasible system was necessary to be pursued. Musk revealed the scaled-back design at the 2017 International Astronomical Congress<ref>Musk, Elon. 2017. ''[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tdUX3ypDVwI Making Life Multiplanetary]''. Adelaide, Australia.</ref> almost exactly a year after the original unveil of the system. Musk also announced that the working name for the spacecraft was BFR, officially the Big Falcon Rocket. The height of the two-stage craft was reduced to one-hundred-six meters, and the diameter was reduced to nine meters.<ref>Dodd, Tim. 2017. "[https://everydayastronaut.com/2017-bfr-vs-2016-its/ 2017 BFR vs 2016 ITS]". Everyday Astronaut. September 29, 2017.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===2018 Starship-Super Heavy=== | ||

| + | This version was presented by Elon Musk during the announcement of Yusaku Maezawa's Dear Moon project, as an evolution of the BFR/BFS concept and Interplanetary Transportation System (ITS) concepts. It had three aerodynamic fins. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===2019 Starship-Booster=== | ||

Originally planned to be constructed of carbon fiber composite, it was changed to a Stainless Steel design in January 2019 .<ref>Popular Mechanics article [https://www.popularmechanics.com/space/rockets/a25953663/elon-muhttps://www.popularmechanics.com/space/rockets/a25953663/elon-musk-spacex-bfr-stainless-steel/sk-spacex-bfr-stainless-steel/]</ref> | Originally planned to be constructed of carbon fiber composite, it was changed to a Stainless Steel design in January 2019 .<ref>Popular Mechanics article [https://www.popularmechanics.com/space/rockets/a25953663/elon-muhttps://www.popularmechanics.com/space/rockets/a25953663/elon-musk-spacex-bfr-stainless-steel/sk-spacex-bfr-stainless-steel/]</ref> | ||

| + | The configuration was also changed to 4 adjustable flaps, or winglets, depending on nomenclature, two at the rear and two at the front. | ||

| − | = | + | {| class="wikitable" |

| − | + | |+ | |

| + | Comparison of various iterations | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | !2016 ITS | ||

| + | !2017 BFR | ||

| + | !2018 Super Heavy-Starship | ||

| + | !2019 Super Heavy-Starship | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Iteration announced | ||

| + | |27 Septemer 2016 | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Stack height | ||

| + | |122 m | ||

| + | |106 m | ||

| + | |118 m | ||

| + | |118 m | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |– First stage height | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |58 m | ||

| + | |63 m | ||

| + | |68 m | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |– Second stage height | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |48 m | ||

| + | |55 m | ||

| + | |50 m | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Diameter † | ||

| + | |12 m | ||

| + | |9 m | ||

| + | |9 m | ||

| + | |9 m | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Principle material | ||

| + | |Carbon fiber | ||

| + | |Carbon fiber | ||

| + | |Carbon fiber | ||

| + | |301 Stainless steel | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |First stage thrust | ||

| + | |128 MN | ||

| + | |48 MN | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |72 MN | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Mass to Low Earth Orbit | ||

| + | |300 t | ||

| + | |150 t | ||

| + | |100 t | ||

| + | |100 t | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Engines | ||

| + | |51 Raptors | ||

| + | |47 Raptors | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |37 Raptors | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |– First stage engines | ||

| + | |42 Raptors | ||

| + | |31 Raptors | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |31 Raptors | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |– Second stage engines | ||

| + | |9 Raptors | ||

| + | |2 Sea-level Raptors | ||

| + | 4 Vacuum Raptors | ||

| + | |7 Sea-level Raptors | ||

| + | |6 Raptors | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Propellant capacity | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |3625* t | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |4500 t | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |– First stage capacity | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |2525* t | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |3300 t | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |– Second stage capacity | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |1100 t | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |1200 t (940t LOX, 260t CH4) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Pressurized volume | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |825 m³ | ||

| + | |1000 m³ | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Principle sources | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |<ref>SpaceX. "[https://www.spacex.com/sites/spacex/files/making_life_multiplanetary-2017.pdf Slideshow: Making Life Multiplanetary]". 2017. </ref><ref>"[http://spacelaunchreport.com/bfr.html#config SpaceX Super Heavy/Starship Components]". 2019. Space Launch Report. December 9, 2019.</ref> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |<ref>"[http://web.archive.org/web/20191230093531/https://www.spacex.com/starship Starship]". SpaceX. 2019. </ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="5" |* Indicates that this number is unofficial | ||

| + | † Diameter has always been the same for the first and second stages | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | + | ==Characteristics of Starship== | |

| + | *85-120 tonnes mass, 9m diameter, 100-150 tonnes of payload to LEO, 100-150 tonnes to Mars. These are target values, the lower the mass of the vehicle, the higher the payload mass will be. Payload volume of 800-1000 m3, depending on Starship length.<ref>https://www.spacex.com/starship</ref> | ||

| − | + | *3 vacuum Raptor engines with 380s ISP and 3 (or six) atmospheric Raptor engines with 330s ISP. Nominal thrust of 2000 kN, (200 tonnes of force per engine) These numbers are subject to change as the engine and the vehicle concepts are under development. | |

| − | + | *120-160 day transportation time to Mars, using [[Aerobraking|aerocapture]] at Mars. | |

| − | + | *Fully reusable, rapid turnover and low maintenance vehicle. | |

| − | + | *Up to 100 passengers to Mars, although this has not been demonstrated yet by SpaceX. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Version 2=== | |

| + | In 2024 Elon Musk described the next version of Starship (version 2) which would be 1.8 meters taller. This featured a new forward flap design (to minimize heating in reentry), increased propellant capacity, and an increase in thrust. This ship will be used from Ship 33 and subsequent flights. <ref>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=umdkFlNO1os </ref> It is not yet known how much this will change the mass to orbit / to Mars. | ||

| − | + | ==Enabling technologies== | |

| + | The fundamental enabling technology of the Starship is [[Landing on Mars|supersonic retro propulsive]] landing on Mars. The use of supersonic retro-propulsion in a critical phase of the Mars entry path allows the vehicle to land heavier payloads that previously thought possible. Although the exact details are not public, the current SpaceX Falcon 9 booster rocket has done flight tests that would confirm the flight path. <ref>AEROTHERMAL ANALYSIS OF REUSABLE LAUNCHER SYSTEMS DURING RETRO-PROPULSION REENTRY AND LANDING [https://elib.dlr.de/120072/1/00040_ECKER.pdf]</ref> | ||

| − | A | + | A second enabling technology is reusability of the booster and of the Starship. This greatly reduces mission cost compared to single use designs and allows for high flight rates. |

| + | A third enabling technology is the capacity of refueling the starship in orbit. This changes the requirements to Reach Mars from a high capacity system to a high flight rate system. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A fourth enabling technology is the use of methane as fuel, than can be provided by In-situ resources production systems on Mars, and therefore allow for the re-use of the spaceship. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A fifth technology is a robust heat shield for Mars and Earth entry. This allows for fast re-use and lower costs, but also for faster transit times, reducing the radiation exposure to travelers. The Spaceship is not necessarily intended to use low energy Hohmann transfer orbits, but higher velocity orbits. These have lower transit times but leave the vehicle with significant velocity when it reaches Mars or Earth. The Starship must then use direct entry and aerodynamic braking to shed the kinetic energy from the extra velocity. More conservative Hohmann transfer orbits may be used for the first flights. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A sixth enabling technology is the use of stainless steel for the rocket body. This has allowed SpaceX to develop the vehicles using rapid prototyping and iterative methods, at the possible cost of reduced payload performances. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Launch pads== | ||

| + | Two launch areas have been built or are under construction. One in Texas, one in Florida. The launch towers that service the vehicle stack use mechanical arms to move the vehicles, and are projected to be used to catch the vehicles at landing time, reducing the mass of the vehicles but adding a requirement for very precise position control at landing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Flightpath== | ||

The NASA Ames research center trajectory browser can be used to explore transit times to Mars and other bodies in the Solar System. [https://trajbrowser.arc.nasa.gov/traj_browser.php Trajectory browser] | The NASA Ames research center trajectory browser can be used to explore transit times to Mars and other bodies in the Solar System. [https://trajbrowser.arc.nasa.gov/traj_browser.php Trajectory browser] | ||

| − | ====== | + | ==Point to point== |

| + | A future use of the Starship as a point to point launch system has been proposed by SpaceX. Large production volumes and a high flight rate would reduce the price of Starship production, and therefore the cost of transportation to Mars. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == See also == | ||

| + | [[List of Launch Systems and Vendors|List of launch systems]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 16:18, 14 August 2024

Starship is the name of the 2019 version of the second stage of the SpaceX reusable super heavy lift vehicle, resting upon the Super Heavy booster. The term "Starship" may also be used to refer to the complete stack of both stages. SpaceX’s Starship spacecraft and Super Heavy rocket (collectively referred to as Starship) represent a fully reusable transportation system designed to carry both crew and cargo to Earth orbit, the Moon, Mars and beyond. Starship will be the world’s most powerful launch vehicle ever developed, with the ability to carry in excess of 100 metric tonnes to Earth orbit. Starship will enter Mars’ atmosphere at 7.5 kilometers per second and decelerate aerodynamically. The vehicle’s heat shield is designed to withstand multiple entries, but given that the vehicle is coming into Mars' atmosphere so hot, we still expect to see some ablation of the heat shield (similar to wear and tear on a brake pad). The engineering video below simulates the physics of Mars entry for Starship.[1]

If SpaceX is able to make this ship work, with rapid turnaround, the cost of launching a kg into Low Earth Orbit will decrease at least ten fold. This will make all space projects (including Mars missions) much cheaper.

Contents

Development history

2016 Interplanetary Transportation System

The origins of Starship are rooted in the Interplanetary Transportation System. This architecture was revealed in a 2016 speech by Elon Musk at the International Astronomical Congress.[2] The concept was conceived as a two-stage spacecraft able to be reused a thousand times and to hold crews of over a hundred people with its primary intent to send people to Mars. The concept would depend upon tanker ships and orbital refueling, and it would extensively utilize in-situ resource utilization to produce the methane fuel required for the return voyage to Earth.[3]

The design was immense, with a twelve meter diameter and depended upon forty-two methane Raptor engines on the booster alone, allowing it to produce thrust of thirteen-thousand metric tons. The stacked system would stretch up one-hundred-twenty-two meters into the sky. Upon stage separation, the booster would return to the launch site, landing propulsively on the launch mounts so that it could quickly be refueled and again flown. The second stage, which in some launches would include a habitat, had nine additional Raptor engines to accelerate the ship to Low Earth Orbit. In order to continue a trip to Mars, the second stage would have to be refueled by one or more tankers.[3]

The proposal of the carbon fiber launch vehicle came with an estimated necessary cost of investment of ten billion dollars by Elon Musk, who suggested that a massive public-private partnership might be the best option for the vehicle. The original timeline of the proposal called for structures and propulsion development to be completed in 2019, when ship testing and orbital testing where to begin. Orbital testing was to be completed in late 2022, and shortly thereafter Mars flights were to begin.[3]

Musk acknowledged that this timeline was incredibly ambitious, but he believed that it was not too unreasonable. Musk took pride in announcing that two components of the system had already been built and were undergoing testing: the twelve-meter carbon fiber tank to store oxidizer in the second stage[4][5] and the first development versions of the Raptor methane full-flow staged combustion engine.[6] Initial tests of the carbon fiber tank proved to be successful, with Musk noting that his company had not "seen any leaks or major issues" when testing the tanks with cryogenic propellent.[7] After heavy testing, the tank was destroyed in February 2017.[8]

2017 Big Falcon Rocket

Over the course of a year, Musk and SpaceX recognized that a smaller, more feasible system was necessary to be pursued. Musk revealed the scaled-back design at the 2017 International Astronomical Congress[9] almost exactly a year after the original unveil of the system. Musk also announced that the working name for the spacecraft was BFR, officially the Big Falcon Rocket. The height of the two-stage craft was reduced to one-hundred-six meters, and the diameter was reduced to nine meters.[10]

2018 Starship-Super Heavy

This version was presented by Elon Musk during the announcement of Yusaku Maezawa's Dear Moon project, as an evolution of the BFR/BFS concept and Interplanetary Transportation System (ITS) concepts. It had three aerodynamic fins.

2019 Starship-Booster

Originally planned to be constructed of carbon fiber composite, it was changed to a Stainless Steel design in January 2019 .[11] The configuration was also changed to 4 adjustable flaps, or winglets, depending on nomenclature, two at the rear and two at the front.

| 2016 ITS | 2017 BFR | 2018 Super Heavy-Starship | 2019 Super Heavy-Starship | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iteration announced | 27 Septemer 2016 | |||

| Stack height | 122 m | 106 m | 118 m | 118 m |

| – First stage height | 58 m | 63 m | 68 m | |

| – Second stage height | 48 m | 55 m | 50 m | |

| Diameter † | 12 m | 9 m | 9 m | 9 m |

| Principle material | Carbon fiber | Carbon fiber | Carbon fiber | 301 Stainless steel |

| First stage thrust | 128 MN | 48 MN | 72 MN | |

| Mass to Low Earth Orbit | 300 t | 150 t | 100 t | 100 t |

| Engines | 51 Raptors | 47 Raptors | 37 Raptors | |

| – First stage engines | 42 Raptors | 31 Raptors | 31 Raptors | |

| – Second stage engines | 9 Raptors | 2 Sea-level Raptors

4 Vacuum Raptors |

7 Sea-level Raptors | 6 Raptors |

| Propellant capacity | 3625* t | 4500 t | ||

| – First stage capacity | 2525* t | 3300 t | ||

| – Second stage capacity | 1100 t | 1200 t (940t LOX, 260t CH4) | ||

| Pressurized volume | 825 m³ | 1000 m³ | ||

| Principle sources | [12][13] | [14] | ||

| * Indicates that this number is unofficial

† Diameter has always been the same for the first and second stages | ||||

Characteristics of Starship

- 85-120 tonnes mass, 9m diameter, 100-150 tonnes of payload to LEO, 100-150 tonnes to Mars. These are target values, the lower the mass of the vehicle, the higher the payload mass will be. Payload volume of 800-1000 m3, depending on Starship length.[15]

- 3 vacuum Raptor engines with 380s ISP and 3 (or six) atmospheric Raptor engines with 330s ISP. Nominal thrust of 2000 kN, (200 tonnes of force per engine) These numbers are subject to change as the engine and the vehicle concepts are under development.

- 120-160 day transportation time to Mars, using aerocapture at Mars.

- Fully reusable, rapid turnover and low maintenance vehicle.

- Up to 100 passengers to Mars, although this has not been demonstrated yet by SpaceX.

Version 2

In 2024 Elon Musk described the next version of Starship (version 2) which would be 1.8 meters taller. This featured a new forward flap design (to minimize heating in reentry), increased propellant capacity, and an increase in thrust. This ship will be used from Ship 33 and subsequent flights. [16] It is not yet known how much this will change the mass to orbit / to Mars.

Enabling technologies

The fundamental enabling technology of the Starship is supersonic retro propulsive landing on Mars. The use of supersonic retro-propulsion in a critical phase of the Mars entry path allows the vehicle to land heavier payloads that previously thought possible. Although the exact details are not public, the current SpaceX Falcon 9 booster rocket has done flight tests that would confirm the flight path. [17]

A second enabling technology is reusability of the booster and of the Starship. This greatly reduces mission cost compared to single use designs and allows for high flight rates.

A third enabling technology is the capacity of refueling the starship in orbit. This changes the requirements to Reach Mars from a high capacity system to a high flight rate system.

A fourth enabling technology is the use of methane as fuel, than can be provided by In-situ resources production systems on Mars, and therefore allow for the re-use of the spaceship.

A fifth technology is a robust heat shield for Mars and Earth entry. This allows for fast re-use and lower costs, but also for faster transit times, reducing the radiation exposure to travelers. The Spaceship is not necessarily intended to use low energy Hohmann transfer orbits, but higher velocity orbits. These have lower transit times but leave the vehicle with significant velocity when it reaches Mars or Earth. The Starship must then use direct entry and aerodynamic braking to shed the kinetic energy from the extra velocity. More conservative Hohmann transfer orbits may be used for the first flights.

A sixth enabling technology is the use of stainless steel for the rocket body. This has allowed SpaceX to develop the vehicles using rapid prototyping and iterative methods, at the possible cost of reduced payload performances.

Launch pads

Two launch areas have been built or are under construction. One in Texas, one in Florida. The launch towers that service the vehicle stack use mechanical arms to move the vehicles, and are projected to be used to catch the vehicles at landing time, reducing the mass of the vehicles but adding a requirement for very precise position control at landing.

Flightpath

The NASA Ames research center trajectory browser can be used to explore transit times to Mars and other bodies in the Solar System. Trajectory browser

Point to point

A future use of the Starship as a point to point launch system has been proposed by SpaceX. Large production volumes and a high flight rate would reduce the price of Starship production, and therefore the cost of transportation to Mars.

See also

References

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Musk, Elon. 2016. Making Humans a Multiplanetary Species. Guadalajara, Mexico.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Interplanetary Transport System". n.d. Spaceflight101.com. Accessed January 4, 2020.

- ↑ "First Development Tank for Mars Ship". 2016. Twitter. September 27, 2016.

- ↑ Mitchell, Jacob. 2016. "Here Is the inside of This Tank for You Guys!" Twitter. September 27, 2016.

- ↑ Musk, Elon. 2016. "SpaceX Propulsion Just Achieved First Firing of the Raptor Interplanetary Transport Engine". Twitter. September 26, 2016.

- ↑ Milberg, Evan. 2016. "SpaceX Successfully Tests Carbon Fiber Tank for Mars Spaceship". Composites Manufacturing. November 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Remains of the ITS Composite Tank in Anacortes, WA". 2017. r/SpaceXLounge on Reddit. February 17, 2017.

- ↑ Musk, Elon. 2017. Making Life Multiplanetary. Adelaide, Australia.

- ↑ Dodd, Tim. 2017. "2017 BFR vs 2016 ITS". Everyday Astronaut. September 29, 2017.

- ↑ Popular Mechanics article [2]

- ↑ SpaceX. "Slideshow: Making Life Multiplanetary". 2017.

- ↑ "SpaceX Super Heavy/Starship Components". 2019. Space Launch Report. December 9, 2019.

- ↑ "Starship". SpaceX. 2019.

- ↑ https://www.spacex.com/starship

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=umdkFlNO1os

- ↑ AEROTHERMAL ANALYSIS OF REUSABLE LAUNCHER SYSTEMS DURING RETRO-PROPULSION REENTRY AND LANDING [3]