Difference between revisions of "Carbon Dioxide Scrubbers"

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

===Chemical Systems=== | ===Chemical Systems=== | ||

| − | These systems scrub CO<sub>2</sub> from the air by bringing it into contact with a substance which attaches itself to the CO<sub>2</sub> in a chemical reaction. Scrubbers can accomplish this with soda lime (a mixture of chemicals including calcium hydroxide, sodium hydroxide, and potassium hydroxide) | + | These systems scrub CO<sub>2</sub> from the air by bringing it into contact with a substance which attaches itself to the CO<sub>2</sub> in a chemical reaction. Scrubbers can accomplish this with soda lime (a mixture of chemicals including calcium hydroxide, sodium hydroxide, and potassium hydroxide), amines (a derivative of ammonia), or potassium superoxide (a substance used in firefighter and mining rebreathers), but the low molecular weight of lithium hydroxide (LiOH) has led to its popularity aboard spacecraft.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":5" /> This reaction creates lithium carbonate (Li<sub>2</sub>CO<sub>3)</sub> and water through the following reaction: |

| − | CO<sub>2</sub> (g) + 2LiOH (s) | + | CO<sub>2</sub> (g) + 2LiOH (s) → Li<sub>2</sub>CO<sub>3</sub> (s) + H<sub>2</sub>O (l) |

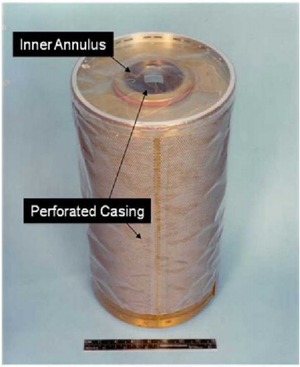

| − | [[File:LiOH_Cannister.png|left|thumb|Lithium Hydroxide canister used aboard the space shuttle with 16 cm ruler for scale. Air is blown through the central annulus, where it moves through a perforated inner layer to come into contact with the LiOH. The remaining, scrubbed air exhausts through the outer perimeter and is recycled back into the spacecraft.<ref name=":6">Matty, C. (2010). Overview of Carbon Dioxide Control Issues During International Space Station/Space Shuttle Joint Docked Operations. ''40th International Conference on Environmental Systems''. Presented at the 40th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Barcelona, Spain. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2010-6251</nowiki></ref>]]The conversion to Li<sub>2</sub>CO<sub>3</sub> is irreversible, meaning that the canisters used for the reaction must be replaced once all of the LiOH is consumed.<ref name=":6" /> | + | [[File:LiOH_Cannister.png|left|thumb|Lithium Hydroxide canister used aboard the space shuttle with 16 cm ruler for scale. Air is blown through the central annulus, where it moves through a perforated inner layer to come into contact with the LiOH. The remaining, scrubbed air exhausts through the outer perimeter and is recycled back into the spacecraft.<ref name=":6">Matty, C. (2010). Overview of Carbon Dioxide Control Issues During International Space Station/Space Shuttle Joint Docked Operations. ''40th International Conference on Environmental Systems''. Presented at the 40th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Barcelona, Spain. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2010-6251</nowiki></ref>]]The conversion to Li<sub>2</sub>CO<sub>3</sub> is irreversible, meaning that the canisters used for the reaction must be replaced once all of the LiOH is consumed.<ref name=":6" /> Apollo 13 provides perhaps the most famous instance of complications arising due to this replacement process:<ref name=":0" /> an explosion in the command module forced all three crewmembers into the lunar module, whose air recycling system was designed for two. The lunar module's LiOH canisters quickly became saturated, and the crew had to improvise extensive modifications using hoses, socks, plastic bags, and duct tape in order to adapt the command module's square canisters to the round lunar module system. |

| − | In addition to the Apollo program, LiOH canisters constituted the primary CO<sub>2</sub> removal system during the Mercury, Gemini, and Space Shuttle programs.<ref name=":1" /> One canister acted as the primary scrubber, with another in place as a backup; as the primary canister became depleted, the backup took over and the primary was replaced, with this alternating cycle repeating over the course of the mission | + | In addition to the Apollo program, LiOH canisters constituted the primary CO<sub>2</sub> removal system during the Mercury, Gemini, and Space Shuttle programs.<ref name=":1" /> One canister acted as the primary scrubber, with another in place as a backup; as the primary canister became depleted, the backup took over and the primary was replaced, with this alternating cycle repeating as many times as necessary until the crew returned to Earth. The longer the mission, the more canisters required. |

| + | |||

| + | Scrubbing the CO<sub>2</sub> which a single crew member exhales over the course of a day requires roughly 1.5 kilograms of LiOH.<ref name=":1" /> Modern LiOH canisters used by NASA contain 3.0 kilograms of LiOH pellets, and the water created during the chemical reaction brings the weight of a depleted canister to around 4.0 kilograms.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":6" /> Russian Soyuz canisters are almost twice as large. This weight, along with the size of the canisters (approximately 6 liters in volume), adds substantial considerations not only to the cost of launching from Earth, but also to returning, since the canisters are not jettisoned into space.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because the number of required canisters increases in direct proportion to mission length, regenerative CO<sub>2</sub> scrubbers become more cost effective than a system based on consumable LiOH after a period of 20-30 days.<ref name=":7" /> Skylab and Mir still employ LiOH canisters in a supplementary capacity, as does the International Space Station, which maintains a minimum contingency reserve capable of sustaining 3 crew members for 15 days, as well as whatever surplus launch vehicles are able to provide.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Longer-term missions such as Skylab, Mir, and the ISS still employ LiOH | ||

===Adsorption Systems=== | ===Adsorption Systems=== | ||

| Line 53: | Line 59: | ||

The project utilized various methods to attenuate the effects of this variance, including CO<sub>2</sub> sequestration via calcium carbonate precipitation, lowering nighttime temperatures to reduce respiration, and storing trimmed biomass in dry areas to slow its decomposition. Notably, an unanticipated, steady decline in oxygen levels—which required the artificial injection of fresh oxygen after dropping to a point where team members were suffering symptoms of altitude sickness—was attributed to additional microbial respiration from organically-enriched soil.<ref>Nelson, M. (2018). Biosphere 2: What Really Happened? Retrieved August 16, 2019, from Dartmouth Alumni Magazine website: <nowiki>https://dartmouthalumnimagazine.com/articles/biosphere-2-what-really-happened</nowiki></ref> Unsealed concrete in the habitat absorbed the CO<sub>2</sub> released by this respiration, and therefore prevented its re-conversion into oxygen via photosynthesis. | The project utilized various methods to attenuate the effects of this variance, including CO<sub>2</sub> sequestration via calcium carbonate precipitation, lowering nighttime temperatures to reduce respiration, and storing trimmed biomass in dry areas to slow its decomposition. Notably, an unanticipated, steady decline in oxygen levels—which required the artificial injection of fresh oxygen after dropping to a point where team members were suffering symptoms of altitude sickness—was attributed to additional microbial respiration from organically-enriched soil.<ref>Nelson, M. (2018). Biosphere 2: What Really Happened? Retrieved August 16, 2019, from Dartmouth Alumni Magazine website: <nowiki>https://dartmouthalumnimagazine.com/articles/biosphere-2-what-really-happened</nowiki></ref> Unsealed concrete in the habitat absorbed the CO<sub>2</sub> released by this respiration, and therefore prevented its re-conversion into oxygen via photosynthesis. | ||

===Potential for Future Missions=== | ===Potential for Future Missions=== | ||

| − | With further investigation, these plant-based systems could potentially fill the air-recycling needs of future space expeditions. Biological means have yet to feature as the primary form of CO<sub>2</sub> scrubbing for spacecraft due to a variety of reasons including mass constraints, the number of plants required per individual, and the energy costs of optimized lighting and air conditioning.<ref name=":3" /><ref>Closing the Loop: Recycling Water and Air in Space. (n.d.). Retrieved August 15, 2019, from NASA.gov website: <nowiki>https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/146558main_RecyclingEDA(final)%204_10_06.pdf</nowiki></ref> The International Space Station, for example, has plants aboard, but not in the quantities necessary to have any appreciable impact on CO<sub>2</sub> concentrations.<ref>Dunn, T. (2015). Dissecting the Technology of “The Martian”: Air—Tested. Retrieved August 15, 2019, from Tested.com website: <nowiki>https://www.tested.com/science/538792-dissecting-technology-martian-air/</nowiki></ref> | + | With further investigation, these plant-based systems could potentially fill the air-recycling needs of future space expeditions. Biological means have yet to feature as the primary form of CO<sub>2</sub> scrubbing for spacecraft due to a variety of reasons including mass constraints, the number of plants required per individual, and the energy costs of optimized lighting and air conditioning.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":7">Closing the Loop: Recycling Water and Air in Space. (n.d.). Retrieved August 15, 2019, from NASA.gov website: <nowiki>https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/146558main_RecyclingEDA(final)%204_10_06.pdf</nowiki></ref> The International Space Station, for example, has plants aboard, but not in the quantities necessary to have any appreciable impact on CO<sub>2</sub> concentrations.<ref>Dunn, T. (2015). Dissecting the Technology of “The Martian”: Air—Tested. Retrieved August 15, 2019, from Tested.com website: <nowiki>https://www.tested.com/science/538792-dissecting-technology-martian-air/</nowiki></ref> |

Yet, the above experiments hint at the possibility of an exclusively bioregenerative system. The ISS has a habitable volume (388 m<sup>3</sup>) slightly larger than the 315 m<sup>3</sup> environment of the successful BIOS-3 experiment, and a pressurized volume on the order of 3 times as large at 932 m<sup>3</sup>.<ref>Garcia, M. (2019). International Space Station Facts and Figures [Text]. Retrieved August 16, 2019, from NASA website: <nowiki>http://www.nasa.gov/feature/facts-and-figures</nowiki></ref> The BIOS-3 experiments supported up to 3 individuals for 180 days,<ref name=":2" /> meaning that the ISS could theoretically recycle air for a crew of at least 8.<ref name=":4">Walker, R. (2015). Could Astronauts Get All Their Oxygen From Algae Or Plants? And Their Food Also? | Science 2.0. Retrieved August 16, 2019, from Science20.com website: <nowiki>https://www.science20.com/robert_inventor/could_astronauts_get_all_their_oxygen_from_algae_or_plants_and_their_food_also-156990</nowiki></ref> | Yet, the above experiments hint at the possibility of an exclusively bioregenerative system. The ISS has a habitable volume (388 m<sup>3</sup>) slightly larger than the 315 m<sup>3</sup> environment of the successful BIOS-3 experiment, and a pressurized volume on the order of 3 times as large at 932 m<sup>3</sup>.<ref>Garcia, M. (2019). International Space Station Facts and Figures [Text]. Retrieved August 16, 2019, from NASA website: <nowiki>http://www.nasa.gov/feature/facts-and-figures</nowiki></ref> The BIOS-3 experiments supported up to 3 individuals for 180 days,<ref name=":2" /> meaning that the ISS could theoretically recycle air for a crew of at least 8.<ref name=":4">Walker, R. (2015). Could Astronauts Get All Their Oxygen From Algae Or Plants? And Their Food Also? | Science 2.0. Retrieved August 16, 2019, from Science20.com website: <nowiki>https://www.science20.com/robert_inventor/could_astronauts_get_all_their_oxygen_from_algae_or_plants_and_their_food_also-156990</nowiki></ref> | ||

Revision as of 06:01, 18 August 2019

volunteer for The Mars Society

It is licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 and may be freely shared, but must include this attribution.

[This is an article in progress, and is currently being written]

Contents

Dangers of Excessive CO2 Concentration

A steady supply of oxygen alone is insufficient to keep astronauts breathing. While the intake of oxygen is essential for respiration, the by-product of this respiration is the exhalation of approximately one kilogram of carbon-dioxide per day.[1] The concentration of this gas in Earth's atmosphere is roughly 0.04%, but in the close confines endured by astronauts, accumulations of CO2 can quickly reach toxic levels.[2]

| CO2 Concentration | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| 1% | Drowsiness |

| 3% | Impaired hearing, increased heart rate and blood pressure, stupor |

| 5% | Shortness of breath, headache, dizziness, confusion |

| 8% | Unconsciousness, muscle tremors, sweating |

| >8% | Death |

NASA has set strict limits of acceptable CO2 concentration on spacecraft. The longer the duration of the flight, the lower the permissible maximum: for example, while allowing a maximum of 2% for a one-hour period, NASA recommends that the concentration not exceed 0.5% over a 1000-day stay[1] (an as-yet hypothetical duration, as the record for longest consecutive stay in space at the time of writing is held by Russian cosmonaut Valery Polyakov at 438 days[3]). The proportionate decrease in concentration acceptability in accordance with duration accounts for the fact that the longer the period of time, the higher the likelihood of CO2-induced behavioral changes negatively affecting missions requiring close personal contact in confined spaces.

Moderating CO2 levels over such a long period of time naturally implies weight and power demands, yet NASA has adopted more stringent regulations than the Navy, which allows up to 2.5% concentrations for submarine personnel over a 24-hour period.[1] While both types of crews operate in a confined area with an artificially-regulated atmosphere, repairing a CO2 removal system in space constitutes a potentially more complex task where one cannot simply surface in the event of an unsuccessful attempt brought on by concentration difficulties. Hypothetically, a well-developed Mars colony could relax such limitations slightly once it is large enough to contain multiple fail-safes and back-ups, thereby reducing the energy demands on the colony as a whole.

Artificial CO2 Scrubbers

To date, spacecraft have regulated CO2 concentrations through artificial means. The simplest way to accomplish this consists of separating the CO2 molecules from the rest of the air and then venting the toxic gas into space.[4] Two types of systems can achieve this separation: chemical scrubbers and adsorbent scrubbers.[1]

Chemical Systems

These systems scrub CO2 from the air by bringing it into contact with a substance which attaches itself to the CO2 in a chemical reaction. Scrubbers can accomplish this with soda lime (a mixture of chemicals including calcium hydroxide, sodium hydroxide, and potassium hydroxide), amines (a derivative of ammonia), or potassium superoxide (a substance used in firefighter and mining rebreathers), but the low molecular weight of lithium hydroxide (LiOH) has led to its popularity aboard spacecraft.[2][4] This reaction creates lithium carbonate (Li2CO3) and water through the following reaction:

CO2 (g) + 2LiOH (s) → Li2CO3 (s) + H2O (l)

The conversion to Li2CO3 is irreversible, meaning that the canisters used for the reaction must be replaced once all of the LiOH is consumed.[5] Apollo 13 provides perhaps the most famous instance of complications arising due to this replacement process:[2] an explosion in the command module forced all three crewmembers into the lunar module, whose air recycling system was designed for two. The lunar module's LiOH canisters quickly became saturated, and the crew had to improvise extensive modifications using hoses, socks, plastic bags, and duct tape in order to adapt the command module's square canisters to the round lunar module system.

In addition to the Apollo program, LiOH canisters constituted the primary CO2 removal system during the Mercury, Gemini, and Space Shuttle programs.[1] One canister acted as the primary scrubber, with another in place as a backup; as the primary canister became depleted, the backup took over and the primary was replaced, with this alternating cycle repeating as many times as necessary until the crew returned to Earth. The longer the mission, the more canisters required.

Scrubbing the CO2 which a single crew member exhales over the course of a day requires roughly 1.5 kilograms of LiOH.[1] Modern LiOH canisters used by NASA contain 3.0 kilograms of LiOH pellets, and the water created during the chemical reaction brings the weight of a depleted canister to around 4.0 kilograms.[1][5] Russian Soyuz canisters are almost twice as large. This weight, along with the size of the canisters (approximately 6 liters in volume), adds substantial considerations not only to the cost of launching from Earth, but also to returning, since the canisters are not jettisoned into space.[1]

Because the number of required canisters increases in direct proportion to mission length, regenerative CO2 scrubbers become more cost effective than a system based on consumable LiOH after a period of 20-30 days.[6] Skylab and Mir still employ LiOH canisters in a supplementary capacity, as does the International Space Station, which maintains a minimum contingency reserve capable of sustaining 3 crew members for 15 days, as well as whatever surplus launch vehicles are able to provide.[1]

Longer-term missions such as Skylab, Mir, and the ISS still employ LiOH

Adsorption Systems

CDRA

Vozdukh

Other Considerations

Future Systems

Biological CO2 Scrubbers

The chief advantage of a biological recycling system over a mechanically-sustained one is simple: plants don't break. Where a machine might suddenly cease to function and require expensive parts shipped from Earth, nature has largely optimized self-repair via evolution. Given the relatively simple level of technology involved in proper lighting, plumbing, and pumps, and provided that no pests or insects are introduced to the sterile conditions of space, plants could potentially be far more reliable than artificial CO2 scrubbers.[7] Furthermore, the right plants could also double as a food source for astronauts or colonists.

Previous Experiments

Several closed-ecosystem experiments conducted on Earth have investigated the viability of a plant-sustained air recycling system. In the 1970s, the BIOS-3 facility in Siberia found that 8m2 of Chlorella algae could maintain the 02/CO2 balance for one individual in a 315 m3 environment.[8]

The Biosphere 2 project in Arizona attempted a larger-scale project over the course of 2 years, sealing 8 participants in a 180,000 m3 facility with an artificial ecosystem.[9] The facility operated in mostly closed-loop conditions, but was exposed to natural sunlight. Daily variance in this light caused CO2 levels to fluctuate substantially according to the relative activity of photosynthesis: while CO2 concentrations dropped during the day, they rose sharply at night when respiration predominated. Seasonal variation was similarly evident, with levels rising in low-light winter months and on cloudy days, while longer sun exposures corresponding with summer months resulted in lower concentrations. December, for example, averaged CO2 levels over twice as high as those in June, with the two months differing by up to 5 hours of sun exposure at their extreme ends.

The project utilized various methods to attenuate the effects of this variance, including CO2 sequestration via calcium carbonate precipitation, lowering nighttime temperatures to reduce respiration, and storing trimmed biomass in dry areas to slow its decomposition. Notably, an unanticipated, steady decline in oxygen levels—which required the artificial injection of fresh oxygen after dropping to a point where team members were suffering symptoms of altitude sickness—was attributed to additional microbial respiration from organically-enriched soil.[10] Unsealed concrete in the habitat absorbed the CO2 released by this respiration, and therefore prevented its re-conversion into oxygen via photosynthesis.

Potential for Future Missions

With further investigation, these plant-based systems could potentially fill the air-recycling needs of future space expeditions. Biological means have yet to feature as the primary form of CO2 scrubbing for spacecraft due to a variety of reasons including mass constraints, the number of plants required per individual, and the energy costs of optimized lighting and air conditioning.[9][6] The International Space Station, for example, has plants aboard, but not in the quantities necessary to have any appreciable impact on CO2 concentrations.[11]

Yet, the above experiments hint at the possibility of an exclusively bioregenerative system. The ISS has a habitable volume (388 m3) slightly larger than the 315 m3 environment of the successful BIOS-3 experiment, and a pressurized volume on the order of 3 times as large at 932 m3.[12] The BIOS-3 experiments supported up to 3 individuals for 180 days,[8] meaning that the ISS could theoretically recycle air for a crew of at least 8.[7]

The algae in these experiments used 18 kW of artificial lighting per person; extrapolating this to 108 kW for a crew of six on the ISS—which could not rely on natural light alone due to regularly being in darkness—would consume the majority of the 120 kW generated by the station's solar arrays.[7][13] The Russian lamps, however, used xenon technology,[7] which is anywhere from ½ to 10 times less efficient than modern LEDs in terms of lumens generated per watt.[14] More efficient lighting could therefore theoretically reduce the energy requirements to somewhere between 11-54 kW, a much more feasible range considering the power output of the ISS.

Given the mass requirements of a plant-based system, such methods are perhaps better suited to future habitats on Mars. In-situ resource utilization techniques will allow colonists to avoid shipping large quantities of water, soil, or oxygen, all of which can be obtained on site.[9] Hydroponic and aeroponic systems provide alternatives to any complications posed by the use of Mars regolith in a soil-based system, although this soil does contain all the nutrients necessary for plant survival once existing perchlorates are removed.[15]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 James, J. T., & Macatangay, A. (2009). Carbon Dioxide – Our Common “Enemy.” 8.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Freudenrich, C. (2011). How is carbon dioxide eliminated aboard a spacecraft? | HowStuffWorks. Retrieved August 15, 2019, from HowStuffWorks website: https://science.howstuffworks.com/carbon-dioxide-eliminated-aboard-spacecraft.htm

- ↑ Wall, M. (2019). Most Extreme Human Spaceflight Records of All Time | Space. Retrieved August 15, 2019, from Soace.com website: https://www.space.com/11337-human-spaceflight-records-50th-anniversary.html

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Port, J. (2016). Oxygen generators and carbon dioxide scrubbers explained. Retrieved August 17, 2019, from Cosmos Magazine website: https://cosmosmagazine.com/technology/oxygen-generators-and-carbon-dioxide-scrubbers-explained

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Matty, C. (2010). Overview of Carbon Dioxide Control Issues During International Space Station/Space Shuttle Joint Docked Operations. 40th International Conference on Environmental Systems. Presented at the 40th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Barcelona, Spain. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2010-6251

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Closing the Loop: Recycling Water and Air in Space. (n.d.). Retrieved August 15, 2019, from NASA.gov website: https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/146558main_RecyclingEDA(final)%204_10_06.pdf

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Walker, R. (2015). Could Astronauts Get All Their Oxygen From Algae Or Plants? And Their Food Also? | Science 2.0. Retrieved August 16, 2019, from Science20.com website: https://www.science20.com/robert_inventor/could_astronauts_get_all_their_oxygen_from_algae_or_plants_and_their_food_also-156990

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Villazon, L. (n.d.). How many plants would I need in an airtight room to be able to breathe? Retrieved August 16, 2019, from BBC Science Focus Magazine website: https://www.sciencefocus.com/science/how-many-plants-would-i-need-in-an-airtight-room-to-be-able-to-breathe/

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Nelson, M., Dempster, W., Alvarez-Romo, N., & MacCallum, T. (1994). Atmospheric dynamics and bioregenerative technologies in a soil-based ecological life support system: Initial results from biosphere 2. Advances in Space Research, 14(11), 417–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-1177(94)90331-X

- ↑ Nelson, M. (2018). Biosphere 2: What Really Happened? Retrieved August 16, 2019, from Dartmouth Alumni Magazine website: https://dartmouthalumnimagazine.com/articles/biosphere-2-what-really-happened

- ↑ Dunn, T. (2015). Dissecting the Technology of “The Martian”: Air—Tested. Retrieved August 15, 2019, from Tested.com website: https://www.tested.com/science/538792-dissecting-technology-martian-air/

- ↑ Garcia, M. (2019). International Space Station Facts and Figures [Text]. Retrieved August 16, 2019, from NASA website: http://www.nasa.gov/feature/facts-and-figures

- ↑ Garcia, M. (2017, July 31). About the Space Station Solar Arrays [Text]. Retrieved August 16, 2019, from NASA website: http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/structure/elements/solar_arrays-about.html

- ↑ Luminous efficacy. (2019). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Luminous_efficacy&oldid=903091057

- ↑ Jordan, G. (2015, October 5). Can Plants Grow with Mars Soil? [Text]. Retrieved August 16, 2019, from NASA website: http://www.nasa.gov/feature/can-plants-grow-with-mars-soil