Heavy Ions

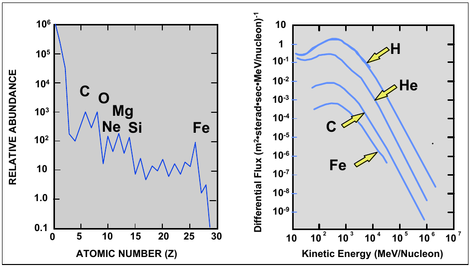

Heavy ions are charged particles heavier than alpha particles.[1] They constitute 1% of cosmic radiation.[2]

Exposures

Health Effects

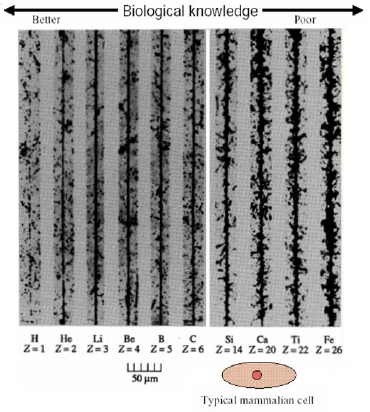

Heavy ions passing through cells transfer more energy into a small volume, compared to other components of cosmic radiation. This concentrated effect can produce qualitatively different types of cell damage.[4] Linear energy transfer (LET) is a measure of the amount of energy deposited in tissue per unit length of a particle's trajectory.[5] LET increases as a function of ion charge and mass, and decreases as a function of velocity.[6] Experimental irradiation of mouse cell cultures has indicated that heavy ions with an LET greater than 10 keV/μm are more likely to cause irreparable cell damage, compared to protons or alpha particles.[7] LET has historically been used to estimate relative biological effectiveness of radiation, but this figure alone might not accurately characterize the damage done by heavy ions.[8]

The health effects of high doses of other types of radiation have been studied by analyzing the health of exposed groups (for example, survivors of nuclear weapon attacks or nuclear power plant accidents). However, in the case of heavy ion radiation, estimates of the risk to astronauts are derived solely from animal model studies and application of biophysics principles. As a result, these estimates are less certain.[4]

Shielding Considerations

Heavy ions generate secondary radiation due to the very high energy of the particles. This means the thickness of radiation shielding needs to be increased over the requirements of solar storm shelters. This is particularly a consideration for long term settlements, where the accumulation of radiation damage from inadequate shielding might lead to increased cancer rates, neurological, and tissue damage over time.

References

- ↑ Heavy ion. (1998, Jul 20). In Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/heavy-ion

- ↑ Schimmerling W. (2011, Feb 5). The Space Radiation Environment: An Introduction. https://three.jsc.nasa.gov/concepts/SpaceRadiationEnviron.pdf

- ↑ Schimmerling W. (2011, Feb 5). The Space Radiation Environment: An Introduction. https://three.jsc.nasa.gov/concepts/SpaceRadiationEnviron.pdf

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Cucinotta FA, Durante M. (2009). Risk of Radiation Carcinogenesis. In Human Health and Performance Risks of Space Exploration Missions. NASA-SP-2009-3405. https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Evidence/reports/EvidenceBook.pdf

- ↑ Wagenaar JD. (1995, Oct 6). Linear Energy Transfer. In Radiation Physics Principles (Section 7.2.3). http://www.med.harvard.edu/JPNM/physics/nmltd/radprin/sect7/7.2/7_2.3.html

- ↑ Wagenaar JD. (1995, Oct 6). Stopping Power. In Radiation Physics Principles (Section 7.1.2). http://www.med.harvard.edu/JPNM/physics/nmltd/radprin/sect7/7.1/7_1.2.html

- ↑ Wilson JW, Cucinotta FA, Thibeault SA, Kim M-H, Shinn JL, & Badavi FF. (1997, Dec). In JW Wilson, J Miller, A Konradi, & FA Cucinotta, (Eds.), Shielding Strategies for Human Space Exploration (pp. 109-149). NASA Conference Publication 3360. http://hdl.handle.net/2060/19980137598

- ↑ Goodhead DT. (2018, Jun 8). Track Structure and the Quality Factor for Space Radiation Cancer Risk. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20180006105