Difference between revisions of "Iapygia quadrangle"

m (→See also) |

m |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

Since the ridges occur in locations with clay, these formations could serve as a marker for clay which requires water for its formation. Water here could have supported life.<ref>Mangold et al. 2007. Mineralogy of the Nili Fossae region with OMEGA/Mars Express data: 2. Aqueous alteration of the crust. J. Geophys. Res., 112, doi:10.1029/2006JE002835.</ref> <ref>Mustard et al., 2007. Mineralogy of the Nili Fossae region with OMEGA/Mars Express data: 1. Ancient impact melt in the Isidis Basin and implications for the transition from the Noachian to Hesperian, J. Geophys. Res., 112.</ref> <ref>Mustard et al., 2009. Composition, Morphology, and Stratigraphy of Noachian Crust around the Isidis Basin, J. Geophys. Res., 114, doi:10.1029/2009JE003349.</ref> | Since the ridges occur in locations with clay, these formations could serve as a marker for clay which requires water for its formation. Water here could have supported life.<ref>Mangold et al. 2007. Mineralogy of the Nili Fossae region with OMEGA/Mars Express data: 2. Aqueous alteration of the crust. J. Geophys. Res., 112, doi:10.1029/2006JE002835.</ref> <ref>Mustard et al., 2007. Mineralogy of the Nili Fossae region with OMEGA/Mars Express data: 1. Ancient impact melt in the Isidis Basin and implications for the transition from the Noachian to Hesperian, J. Geophys. Res., 112.</ref> <ref>Mustard et al., 2009. Composition, Morphology, and Stratigraphy of Noachian Crust around the Isidis Basin, J. Geophys. Res., 114, doi:10.1029/2009JE003349.</ref> | ||

| − | <gallery class="center" widths=" | + | <gallery class="center" widths="380px" heights="360px"> |

Image:Dike near Huygens crater.jpg|Dike near the crater [[Huygens]] shows up as narrow dark line running from upper left to lower right, as seen by [[THEMIS]]. | Image:Dike near Huygens crater.jpg|Dike near the crater [[Huygens]] shows up as narrow dark line running from upper left to lower right, as seen by [[THEMIS]]. | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

==Layers== | ==Layers== | ||

| + | |||

Many places on Mars show rocks arranged in layers. Rock can form layers in a variety of ways. Volcanoes, wind, or water can produce layers.<ref>http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu?PSP_008437_1750 |title=HiRISE | High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment |publisher=Hirise.lpl.arizona.edu?psp_008437_1750 |</ref> | Many places on Mars show rocks arranged in layers. Rock can form layers in a variety of ways. Volcanoes, wind, or water can produce layers.<ref>http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu?PSP_008437_1750 |title=HiRISE | High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment |publisher=Hirise.lpl.arizona.edu?psp_008437_1750 |</ref> | ||

A detailed discussion of layering with many Martian examples can be found in Sedimentary Geology of Mars.<ref>Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken (eds.). 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM.</ref> Layers can be hardened by the action of groundwater. Martian ground water probably moved hundreds of kilometers, and in the process it dissolved many minerals from the rock it passed through. When ground water surfaces in low areas containing sediments, water evaporates in the thin atmosphere and leaves behind minerals as deposits and/or cementing agents. Consequently, layers of dust could not later easily erode away since they were cemented together. | A detailed discussion of layering with many Martian examples can be found in Sedimentary Geology of Mars.<ref>Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken (eds.). 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM.</ref> Layers can be hardened by the action of groundwater. Martian ground water probably moved hundreds of kilometers, and in the process it dissolved many minerals from the rock it passed through. When ground water surfaces in low areas containing sediments, water evaporates in the thin atmosphere and leaves behind minerals as deposits and/or cementing agents. Consequently, layers of dust could not later easily erode away since they were cemented together. | ||

| − | <gallery class="center" widths=" | + | <gallery class="center" widths="380px" heights="360px"> |

File: Wikiesp 035761 1520layers.jpg|Layers in a valley East of Terby Crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | File: Wikiesp 035761 1520layers.jpg|Layers in a valley East of Terby Crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ||

| Line 45: | Line 46: | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| − | <gallery class="center" widths=" | + | <gallery class="center" widths="380px" heights="360px"> |

ESP 047841 1515layers.jpg|Wide view of layered features, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ESP 047841 1515layers.jpg|Wide view of layered features, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ||

| Line 56: | Line 57: | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| − | <gallery class="center" widths=" | + | <gallery class="center" widths="380px" heights="360px"> |

ESP 052495 1505layers.jpg|Wide view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ESP 052495 1505layers.jpg|Wide view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ||

| − | |||

52495 1505layers.jpg|Close view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | 52495 1505layers.jpg|Close view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ||

52495 1505layersclose.jpg|Close view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Rectangle shows the size of a football field for scale. | 52495 1505layersclose.jpg|Close view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Rectangle shows the size of a football field for scale. | ||

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| − | <gallery class="center" widths=" | + | <gallery class="center" widths="380px" heights="360px"> |

File:ESP 054710 1495layers.jpg|Wide view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | File:ESP 054710 1495layers.jpg|Wide view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

Impact craters generally have a rim with ejecta around them, in contrast volcanic craters usually do not have a rim or ejecta deposits.<ref>Hugh H. Kieffer|title=Mars|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NoDvAAAAMAAJ|accessdate=7 March 2011|date=1992|publisher=University of Arizona Press|</ref> Sometimes craters will display layers. Since the collision that produces a crater is like a powerful explosion, rocks from deep underground are tossed unto the surface. Hence, craters can show us what lies deep under the surface. | Impact craters generally have a rim with ejecta around them, in contrast volcanic craters usually do not have a rim or ejecta deposits.<ref>Hugh H. Kieffer|title=Mars|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NoDvAAAAMAAJ|accessdate=7 March 2011|date=1992|publisher=University of Arizona Press|</ref> Sometimes craters will display layers. Since the collision that produces a crater is like a powerful explosion, rocks from deep underground are tossed unto the surface. Hence, craters can show us what lies deep under the surface. | ||

| − | <gallery class="center" widths=" | + | <gallery class="center" widths="380px" heights="360px"> |

Image:Schaeberle Crater.JPG|Small crater in [[Schaeberle Crater]], as seen by HiRISE. Image on right is an enlargement of the other image. Scale bar is 500 meters long. | Image:Schaeberle Crater.JPG|Small crater in [[Schaeberle Crater]], as seen by HiRISE. Image on right is an enlargement of the other image. Scale bar is 500 meters long. | ||

Image:Wiinslow Crater.JPG|[[Winslow Crater]], as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 1000 meters long. Crater is named after the town of [[Winslow, Arizona]], just east of [[Meteor Crater]] because of its similar size and infrared characteristics. | Image:Wiinslow Crater.JPG|[[Winslow Crater]], as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 1000 meters long. Crater is named after the town of [[Winslow, Arizona]], just east of [[Meteor Crater]] because of its similar size and infrared characteristics. | ||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

Carbonates (calcium or iron carbonates) were discovered in a crater on the rim of Huygens Crater.<ref>Wray, J., et al. 2016. Orbital evidence for more widespread carbonate‐bearing rocks on Mars. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets: 121, Issue 4</ref> <ref>doi=10.1002/2015JE004972| title=Orbital evidence for more widespread carbonate-bearing rocks on Mars| journal=Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets| volume=121| issue=4| pages=652–677| year=2016| last1=Wray| first1=James J.| last2=Murchie| first2=Scott L.| last3=Bishop| first3=Janice L.| last4=Ehlmann| first4=Bethany L.| last5=Milliken| first5=Ralph E.| last6=Wilhelm| first6=Mary Beth| last7=Seelos| first7=Kimberly D.| last8=Chojnacki| first8=Matthew|</ref> The impact on the rim exposed material that had been dug up from the impact that created Huygens. These minerals represent evidence that Mars once was had a thicker carbon dioxide atmosphere with abundant moisture. These kinds of carbonates only form when there is a lot of water. They were found with the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) instrument on the [[Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter]]. Earlier, the instrument had detected clay minerals. The carbonates were found near the clay minerals. Both of these minerals form in wet environments. It is supposed that billions of years age Mars was much warmer and wetter. At that time, carbonates would have formed from water and the carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere. Later the deposits of carbonate would have been buried. The double impact has now exposed the minerals. Earth has vast carbonate deposits in the form of limestone.<ref name="jpl.nasa.gov"/> | Carbonates (calcium or iron carbonates) were discovered in a crater on the rim of Huygens Crater.<ref>Wray, J., et al. 2016. Orbital evidence for more widespread carbonate‐bearing rocks on Mars. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets: 121, Issue 4</ref> <ref>doi=10.1002/2015JE004972| title=Orbital evidence for more widespread carbonate-bearing rocks on Mars| journal=Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets| volume=121| issue=4| pages=652–677| year=2016| last1=Wray| first1=James J.| last2=Murchie| first2=Scott L.| last3=Bishop| first3=Janice L.| last4=Ehlmann| first4=Bethany L.| last5=Milliken| first5=Ralph E.| last6=Wilhelm| first6=Mary Beth| last7=Seelos| first7=Kimberly D.| last8=Chojnacki| first8=Matthew|</ref> The impact on the rim exposed material that had been dug up from the impact that created Huygens. These minerals represent evidence that Mars once was had a thicker carbon dioxide atmosphere with abundant moisture. These kinds of carbonates only form when there is a lot of water. They were found with the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) instrument on the [[Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter]]. Earlier, the instrument had detected clay minerals. The carbonates were found near the clay minerals. Both of these minerals form in wet environments. It is supposed that billions of years age Mars was much warmer and wetter. At that time, carbonates would have formed from water and the carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere. Later the deposits of carbonate would have been buried. The double impact has now exposed the minerals. Earth has vast carbonate deposits in the form of limestone.<ref name="jpl.nasa.gov"/> | ||

| − | <gallery class="center" widths=" | + | <gallery class="center" widths="380px" heights="360px"> |

Image:Huygens Crater.jpg|[[Huygens Crater]] with circle showing place where carbonate was discovered. This deposit may represent a time when Mars had abundant liquid water on its surface. Scale bar is 259 km long. | Image:Huygens Crater.jpg|[[Huygens Crater]] with circle showing place where carbonate was discovered. This deposit may represent a time when Mars had abundant liquid water on its surface. Scale bar is 259 km long. | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

==Evidence of rivers== | ==Evidence of rivers== | ||

| + | |||

It is accepted that water once flowed in river valleys on Mars. Images of curved channels have been seen in images from Mars spacecraft dating back to the early seventies with the Mariner 9 orbiter.<ref>Baker, V. 1982. The Channels of Mars. Univ. of Tex. Press, Austin, TX</ref> <ref>Baker, V., R. Strom, R., V. Gulick, J. Kargel, G. Komatsu, V. Kale. 1991. Ancient oceans, ice sheets and the hydrological cycle on Mars. Nature 352, 589–594.</ref> <ref>Carr, M. 1979. Formation of Martian flood features by release of water from confined aquifers. J. Geophys. Res. 84, 2995–300.</ref><ref>Komar, P. 1979. Comparisons of the hydraulics of water flows in Martian outflow channels with flows of similar scale on Earth. Icarus 37, 156–181.</ref> | It is accepted that water once flowed in river valleys on Mars. Images of curved channels have been seen in images from Mars spacecraft dating back to the early seventies with the Mariner 9 orbiter.<ref>Baker, V. 1982. The Channels of Mars. Univ. of Tex. Press, Austin, TX</ref> <ref>Baker, V., R. Strom, R., V. Gulick, J. Kargel, G. Komatsu, V. Kale. 1991. Ancient oceans, ice sheets and the hydrological cycle on Mars. Nature 352, 589–594.</ref> <ref>Carr, M. 1979. Formation of Martian flood features by release of water from confined aquifers. J. Geophys. Res. 84, 2995–300.</ref><ref>Komar, P. 1979. Comparisons of the hydraulics of water flows in Martian outflow channels with flows of similar scale on Earth. Icarus 37, 156–181.</ref> | ||

Vallis (plural ''valles'') is the Latin word for ''valley''. It is used in planetary geology for the naming of landform features on other planets that could be old river valleys. Such valleys were were discovered on Mars, when probes first orbited Mars. In the seventies, the Viking Orbiters caused a revolution in our ideas about water on Mars; huge river valleys were found in many areas. Spacecraft cameras showed that floods of water broke through dams, carved deep valleys, eroded grooves into bedrock, and traveled thousands of kilometers.</ref> <ref>Hugh H. Kieffer|title=Mars|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NoDvAAAAMAAJ|accessdate=7 March 2011|date=1992|publisher=University of Arizona Press|</ref> <ref>Raeburn, P. 1998. Uncovering the Secrets of the Red Planet Mars. National Geographic Society. Washington D.C.</ref> <ref>Moore, P. et al. 1990. The Atlas of the Solar System. Mitchell Beazley Publishers NY, NY.</ref> Some valles on Mars (Mangala Vallis, Athabasca Vallis, Granicus Vallis, and Tinjar Valles) clearly begin at grabens. Grabens have a center section of rock lower than its sides; the sides are steep faults. On the other hand, some of the large outflow channels begin in rubble-filled low areas called chaos or chaotic terrain. It has been suggested that massive amounts of water were trapped under pressure beneath a thick cryosphere (layer of frozen ground), then the water was suddenly released, perhaps when the cryosphere was broken by a fault.<ref>Carr, M. 1979. Formation of martian flood features by release of water from confined aquifers. J. Geophys. Res. 84: 2995-3007.</ref> <ref>Hanna, J. and R. Phillips. 2005. Tectonic pressurization of aquifers in the formation of Mangala and Athabasca Valles on Mars. LPSC XXXVI. Abstract 2261.</ref> | Vallis (plural ''valles'') is the Latin word for ''valley''. It is used in planetary geology for the naming of landform features on other planets that could be old river valleys. Such valleys were were discovered on Mars, when probes first orbited Mars. In the seventies, the Viking Orbiters caused a revolution in our ideas about water on Mars; huge river valleys were found in many areas. Spacecraft cameras showed that floods of water broke through dams, carved deep valleys, eroded grooves into bedrock, and traveled thousands of kilometers.</ref> <ref>Hugh H. Kieffer|title=Mars|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NoDvAAAAMAAJ|accessdate=7 March 2011|date=1992|publisher=University of Arizona Press|</ref> <ref>Raeburn, P. 1998. Uncovering the Secrets of the Red Planet Mars. National Geographic Society. Washington D.C.</ref> <ref>Moore, P. et al. 1990. The Atlas of the Solar System. Mitchell Beazley Publishers NY, NY.</ref> Some valles on Mars (Mangala Vallis, Athabasca Vallis, Granicus Vallis, and Tinjar Valles) clearly begin at grabens. Grabens have a center section of rock lower than its sides; the sides are steep faults. On the other hand, some of the large outflow channels begin in rubble-filled low areas called chaos or chaotic terrain. It has been suggested that massive amounts of water were trapped under pressure beneath a thick cryosphere (layer of frozen ground), then the water was suddenly released, perhaps when the cryosphere was broken by a fault.<ref>Carr, M. 1979. Formation of martian flood features by release of water from confined aquifers. J. Geophys. Res. 84: 2995-3007.</ref> <ref>Hanna, J. and R. Phillips. 2005. Tectonic pressurization of aquifers in the formation of Mangala and Athabasca Valles on Mars. LPSC XXXVI. Abstract 2261.</ref> | ||

| − | <gallery class="center" widths=" | + | <gallery class="center" widths="380px" heights="360px"> |

ESP 036051 1515iapyagiachannel.jpg|Channel within a larger channel, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ESP 036051 1515iapyagiachannel.jpg|Channel within a larger channel, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ||

File:Libya Montes - THEMIS image.JPG|[[Libya Montes]] with valley networks (THEMIS). | File:Libya Montes - THEMIS image.JPG|[[Libya Montes]] with valley networks (THEMIS). | ||

| Line 132: | Line 134: | ||

==Dunes== | ==Dunes== | ||

| + | |||

The Iapygia quadrangle contains some dunes. Dunes are common on Mars. The Martian surface is old—billions of year old—there has been a long time for rocks to break down into sand. Some dunes are barchans. Barchans occur where there is plenty of sand. When there are perfect conditions for producing sand dunes, steady wind in one direction and just enough sand, a barchan sand dune forms. Barchans have a gentle slope on the wind side and a much steeper slope on the lee side where horns or a notch often forms.<ref>Pye|first=Kenneth|title=Aeolian Sand and Sand Dunes|year=2008|publisher=Springer|isbn=9783540859109|pages=138|author2=Haim Tsoa</ref> The whole dune may appear to move with the wind. Observing dunes on Mars can tell us how strong the winds are, as well as their direction. If pictures are taken at regular intervals, one may see changes in the dunes or possibly in ripples on the dune’s surface. On Mars dunes are often dark in color because they were formed from the common, volcanic rock basalt. In the dry environment, dark minerals in basalt, like olivine and pyroxene, do not break down as they do on Earth. Although rare, some dark sand is found on Hawaii which also has many volcanoes discharging basalt. Barchan is a Russian term because this type of dune was first seen in the desert regions of Turkistan.<ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/53068/barchan |title = Barchan | sand dune}}</ref> Pictures below show sand dunes in this quadrangle. | The Iapygia quadrangle contains some dunes. Dunes are common on Mars. The Martian surface is old—billions of year old—there has been a long time for rocks to break down into sand. Some dunes are barchans. Barchans occur where there is plenty of sand. When there are perfect conditions for producing sand dunes, steady wind in one direction and just enough sand, a barchan sand dune forms. Barchans have a gentle slope on the wind side and a much steeper slope on the lee side where horns or a notch often forms.<ref>Pye|first=Kenneth|title=Aeolian Sand and Sand Dunes|year=2008|publisher=Springer|isbn=9783540859109|pages=138|author2=Haim Tsoa</ref> The whole dune may appear to move with the wind. Observing dunes on Mars can tell us how strong the winds are, as well as their direction. If pictures are taken at regular intervals, one may see changes in the dunes or possibly in ripples on the dune’s surface. On Mars dunes are often dark in color because they were formed from the common, volcanic rock basalt. In the dry environment, dark minerals in basalt, like olivine and pyroxene, do not break down as they do on Earth. Although rare, some dark sand is found on Hawaii which also has many volcanoes discharging basalt. Barchan is a Russian term because this type of dune was first seen in the desert regions of Turkistan.<ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/53068/barchan |title = Barchan | sand dune}}</ref> Pictures below show sand dunes in this quadrangle. | ||

Some of the wind on Mars is created when the dry ice at the poles is heated in the spring. At that time, the solid carbon dioxide (dry ice) sublimates or changes directly to a gas and rushes away at high speeds. Each Martian year 30% of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere freezes out and covers the pole that is experiencing winter, so there is a great potential for strong winds.<ref>Mellon, J. T. |author2=Feldman, W. C. |author3=Prettyman, T. H. |title=The presence and stability of ground ice in the southern hemisphere of Mars|journal=Icarus|year=2003|volume=169|issue=2|pages=324–340|</ref> | Some of the wind on Mars is created when the dry ice at the poles is heated in the spring. At that time, the solid carbon dioxide (dry ice) sublimates or changes directly to a gas and rushes away at high speeds. Each Martian year 30% of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere freezes out and covers the pole that is experiencing winter, so there is a great potential for strong winds.<ref>Mellon, J. T. |author2=Feldman, W. C. |author3=Prettyman, T. H. |title=The presence and stability of ground ice in the southern hemisphere of Mars|journal=Icarus|year=2003|volume=169|issue=2|pages=324–340|</ref> | ||

| − | <gallery class="center" widths=" | + | |

| + | <gallery class="center" widths="380px" heights="360px"> | ||

Image:Dunes in Iapygia.JPG|Sand [[dunes]] often form in low areas ([[Mars Global Surveyor]]). | Image:Dunes in Iapygia.JPG|Sand [[dunes]] often form in low areas ([[Mars Global Surveyor]]). | ||

Image:ESP 034694 1555whitepurple.jpg|Dunes in [[Schaeberle (Martian crater)]] , as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. | Image:ESP 034694 1555whitepurple.jpg|Dunes in [[Schaeberle (Martian crater)]] , as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. | ||

ESP 036131 1675iapygiadikedunes.jpg|Dunes and craters, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ESP 036131 1675iapygiadikedunes.jpg|Dunes and craters, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

==Landslides== | ==Landslides== | ||

| − | <gallery class="center" widths=" | + | |

| + | <gallery class="center" widths="380px" heights="360px"> | ||

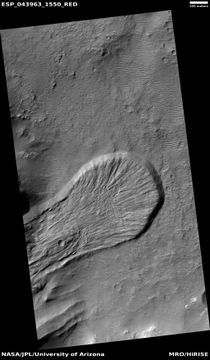

ESP 043963 1550landslide.jpg|Landslide in a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ESP 043963 1550landslide.jpg|Landslide in a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

==Other features in Iapygia quadrangle== | ==Other features in Iapygia quadrangle== | ||

| − | <gallery class="center" widths=" | + | |

| + | <gallery class="center" widths="380px" heights="360px"> | ||

47577 1515blocks.jpg|Surface breaking up into cube-shaped blocks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | 47577 1515blocks.jpg|Surface breaking up into cube-shaped blocks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ||

ESP 047603 1510gullies.jpg|Gullies in crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ESP 047603 1510gullies.jpg|Gullies in crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program | ||

| Line 151: | Line 158: | ||

File:ESP 055528 1610contact.jpg|Contact showing light and dark-toned materials, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Light-toned materials typically contain water in minerals. | File:ESP 055528 1610contact.jpg|Contact showing light and dark-toned materials, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Light-toned materials typically contain water in minerals. | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| − | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 11:42, 6 March 2020

| MC-21 | Iapygia | 0–30° S | 45–90° E | Quadrangles | Atlas |

The Iapygia quadrangle covers the area from 0° to 30° south latitude and from 270° to 315° west longitude (90-45 W). Parts of the regions called Tyrrhena Terra and Terra Sabaea are found in this quadrangle. The largest crater in this quadrangle is Huygens . Some interesting features in this quadrangle are dikes.[1] layers in Terby crater, and the presence of carbonates on the rim of Huygens crater.[2]

Contents

Dikes

Near Huygens, especially just to the east of it, are a number of narrow ridges which appear to be the remnants of dikes, like the ones around Shiprock, New Mexico. The dikes were once under the surface, but have now been eroded. Dikes are magma-filled cracks that often carry lava to the surface. Dikes by definition cut across rock layers. Dikes form when magma rises up in a fault (crack) in the rock. They are generally hard and resistant to erosion; thus they are left standing as a wall after erosion has removed the softer ground around them. Some dikes on earth are associated with mineral deposits.[3] Discovering dikes on Mars means that perhaps future colonists will be able to mine needed minerals on Mars, instead of transporting them all the way from the Earth. Some features look like dikes, but may be what has been called linear ridge networks.[4] Ridges often appear as mostly straight segments that intersect in a lattice-like manner. They are hundreds of meters long, tens of meters high, and several meters wide. One explanation for their existence is that impacts created fractures in the surface; these fractures later acted as channels for fluids. Fluids cemented the structures. With the passage of time, surrounding material was eroded away, thereby leaving hard ridges behind. However, this is only one idea. There are others. We do not know exactly how they were made. Since the ridges occur in locations with clay, these formations could serve as a marker for clay which requires water for its formation. Water here could have supported life.[5] [6] [7]

Possible dikes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Arrows point to possible dikes, which appear as relatively straight, narrow ridges.

Layers

Many places on Mars show rocks arranged in layers. Rock can form layers in a variety of ways. Volcanoes, wind, or water can produce layers.[8] A detailed discussion of layering with many Martian examples can be found in Sedimentary Geology of Mars.[9] Layers can be hardened by the action of groundwater. Martian ground water probably moved hundreds of kilometers, and in the process it dissolved many minerals from the rock it passed through. When ground water surfaces in low areas containing sediments, water evaporates in the thin atmosphere and leaves behind minerals as deposits and/or cementing agents. Consequently, layers of dust could not later easily erode away since they were cemented together.

Layers in Terby crater, as seen by HiRISE. Layers may have formed when the Hellas basin was filled with water.

Terby Crater layers as seen by HiRISE.

- 4File:7577 1515layersclose2.jpg

Layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Craters

Impact craters generally have a rim with ejecta around them, in contrast volcanic craters usually do not have a rim or ejecta deposits.[10] Sometimes craters will display layers. Since the collision that produces a crater is like a powerful explosion, rocks from deep underground are tossed unto the surface. Hence, craters can show us what lies deep under the surface.

Small crater in Schaeberle Crater, as seen by HiRISE. Image on right is an enlargement of the other image. Scale bar is 500 meters long.

Winslow Crater, as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 1000 meters long. Crater is named after the town of Winslow, Arizona, just east of Meteor Crater because of its similar size and infrared characteristics.

- Saheki Crater Alluvial Fan.JPG

Saheki Crater Alluvial Fan, as seen by HiRISE.

Suzhi Crater, as seen by CTX camera (on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter). Light-toned layer is visible on the floor.

Jarry-Desloges Crater, as seen by CTX camera (on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter).

Dunes on floor of Jarry-Desloges Crater, as seen by CTX camera (on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter). Note: this is an enlargement of the previous image of Jarry-Desloges Crater.

Fournier Crater, as seen by CTX camera (onMars Reconnaissance Orbiter). The central mound is visible in the middle.

Niesten Crater, as seen by CTX camera (on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter) and MOLA. MOLA colors show elevations. The CTX image came from the rectangle shown in the MOLA image.

Millochau Crater, as seen by CTX camera (on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter).

Carbonates

Carbonates (calcium or iron carbonates) were discovered in a crater on the rim of Huygens Crater.[11] [12] The impact on the rim exposed material that had been dug up from the impact that created Huygens. These minerals represent evidence that Mars once was had a thicker carbon dioxide atmosphere with abundant moisture. These kinds of carbonates only form when there is a lot of water. They were found with the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) instrument on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Earlier, the instrument had detected clay minerals. The carbonates were found near the clay minerals. Both of these minerals form in wet environments. It is supposed that billions of years age Mars was much warmer and wetter. At that time, carbonates would have formed from water and the carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere. Later the deposits of carbonate would have been buried. The double impact has now exposed the minerals. Earth has vast carbonate deposits in the form of limestone.[13]

Huygens Crater with circle showing place where carbonate was discovered. This deposit may represent a time when Mars had abundant liquid water on its surface. Scale bar is 259 km long.

Evidence of rivers

It is accepted that water once flowed in river valleys on Mars. Images of curved channels have been seen in images from Mars spacecraft dating back to the early seventies with the Mariner 9 orbiter.[14] [15] [16][17] Vallis (plural valles) is the Latin word for valley. It is used in planetary geology for the naming of landform features on other planets that could be old river valleys. Such valleys were were discovered on Mars, when probes first orbited Mars. In the seventies, the Viking Orbiters caused a revolution in our ideas about water on Mars; huge river valleys were found in many areas. Spacecraft cameras showed that floods of water broke through dams, carved deep valleys, eroded grooves into bedrock, and traveled thousands of kilometers.</ref> [18] [19] [20] Some valles on Mars (Mangala Vallis, Athabasca Vallis, Granicus Vallis, and Tinjar Valles) clearly begin at grabens. Grabens have a center section of rock lower than its sides; the sides are steep faults. On the other hand, some of the large outflow channels begin in rubble-filled low areas called chaos or chaotic terrain. It has been suggested that massive amounts of water were trapped under pressure beneath a thick cryosphere (layer of frozen ground), then the water was suddenly released, perhaps when the cryosphere was broken by a fault.[21] [22]

Libya Montes with valley networks (THEMIS).

Dunes

The Iapygia quadrangle contains some dunes. Dunes are common on Mars. The Martian surface is old—billions of year old—there has been a long time for rocks to break down into sand. Some dunes are barchans. Barchans occur where there is plenty of sand. When there are perfect conditions for producing sand dunes, steady wind in one direction and just enough sand, a barchan sand dune forms. Barchans have a gentle slope on the wind side and a much steeper slope on the lee side where horns or a notch often forms.[23] The whole dune may appear to move with the wind. Observing dunes on Mars can tell us how strong the winds are, as well as their direction. If pictures are taken at regular intervals, one may see changes in the dunes or possibly in ripples on the dune’s surface. On Mars dunes are often dark in color because they were formed from the common, volcanic rock basalt. In the dry environment, dark minerals in basalt, like olivine and pyroxene, do not break down as they do on Earth. Although rare, some dark sand is found on Hawaii which also has many volcanoes discharging basalt. Barchan is a Russian term because this type of dune was first seen in the desert regions of Turkistan.[24] Pictures below show sand dunes in this quadrangle. Some of the wind on Mars is created when the dry ice at the poles is heated in the spring. At that time, the solid carbon dioxide (dry ice) sublimates or changes directly to a gas and rushes away at high speeds. Each Martian year 30% of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere freezes out and covers the pole that is experiencing winter, so there is a great potential for strong winds.[25]

Sand dunes often form in low areas (Mars Global Surveyor).

Dunes in Schaeberle (Martian crater) , as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program.

Landslides

Other features in Iapygia quadrangle

See also

References

- ↑ Head, J. et al. 2006. The Huygens-Hellas giant dike system on Mars: Implications for Late Noachian-Early Hesperian volcanic resurfacing and climatic evolution. Geology. 34:4: 285-288.

- ↑ http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.cfm?release=2011-071&rn=news.xml&rst=2929 | title=Some of Mars' Missing Carbon Dioxide May be Buried

- ↑ Head, J. et al. 2006. The Huygens-Hellas giant dike system on Mars: Implications for Late Noachian-Early Hesperian volcanic resurfacing and climatic evolution. Geology. 34:4: 285-288.

- ↑ Head, J., J. Mustard. 2006. Breccia dikes and crater-related faults in impact craters on Mars: Erosion and exposure on the floor of a crater 75 km in diameter at the dichotomy boundary, Meteorit. Planet Science: 41, 1675-1690.

- ↑ Mangold et al. 2007. Mineralogy of the Nili Fossae region with OMEGA/Mars Express data: 2. Aqueous alteration of the crust. J. Geophys. Res., 112, doi:10.1029/2006JE002835.

- ↑ Mustard et al., 2007. Mineralogy of the Nili Fossae region with OMEGA/Mars Express data: 1. Ancient impact melt in the Isidis Basin and implications for the transition from the Noachian to Hesperian, J. Geophys. Res., 112.

- ↑ Mustard et al., 2009. Composition, Morphology, and Stratigraphy of Noachian Crust around the Isidis Basin, J. Geophys. Res., 114, doi:10.1029/2009JE003349.

- ↑ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu?PSP_008437_1750 |title=HiRISE | High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment |publisher=Hirise.lpl.arizona.edu?psp_008437_1750 |

- ↑ Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken (eds.). 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM.

- ↑ Hugh H. Kieffer|title=Mars|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NoDvAAAAMAAJ%7Caccessdate=7 March 2011|date=1992|publisher=University of Arizona Press|

- ↑ Wray, J., et al. 2016. Orbital evidence for more widespread carbonate‐bearing rocks on Mars. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets: 121, Issue 4

- ↑ doi=10.1002/2015JE004972| title=Orbital evidence for more widespread carbonate-bearing rocks on Mars| journal=Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets| volume=121| issue=4| pages=652–677| year=2016| last1=Wray| first1=James J.| last2=Murchie| first2=Scott L.| last3=Bishop| first3=Janice L.| last4=Ehlmann| first4=Bethany L.| last5=Milliken| first5=Ralph E.| last6=Wilhelm| first6=Mary Beth| last7=Seelos| first7=Kimberly D.| last8=Chojnacki| first8=Matthew|

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedjpl.nasa.gov - ↑ Baker, V. 1982. The Channels of Mars. Univ. of Tex. Press, Austin, TX

- ↑ Baker, V., R. Strom, R., V. Gulick, J. Kargel, G. Komatsu, V. Kale. 1991. Ancient oceans, ice sheets and the hydrological cycle on Mars. Nature 352, 589–594.

- ↑ Carr, M. 1979. Formation of Martian flood features by release of water from confined aquifers. J. Geophys. Res. 84, 2995–300.

- ↑ Komar, P. 1979. Comparisons of the hydraulics of water flows in Martian outflow channels with flows of similar scale on Earth. Icarus 37, 156–181.

- ↑ Hugh H. Kieffer|title=Mars|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NoDvAAAAMAAJ%7Caccessdate=7 March 2011|date=1992|publisher=University of Arizona Press|

- ↑ Raeburn, P. 1998. Uncovering the Secrets of the Red Planet Mars. National Geographic Society. Washington D.C.

- ↑ Moore, P. et al. 1990. The Atlas of the Solar System. Mitchell Beazley Publishers NY, NY.

- ↑ Carr, M. 1979. Formation of martian flood features by release of water from confined aquifers. J. Geophys. Res. 84: 2995-3007.

- ↑ Hanna, J. and R. Phillips. 2005. Tectonic pressurization of aquifers in the formation of Mangala and Athabasca Valles on Mars. LPSC XXXVI. Abstract 2261.

- ↑ Pye|first=Kenneth|title=Aeolian Sand and Sand Dunes|year=2008|publisher=Springer|isbn=9783540859109|pages=138|author2=Haim Tsoa

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Mellon, J. T. |author2=Feldman, W. C. |author3=Prettyman, T. H. |title=The presence and stability of ground ice in the southern hemisphere of Mars|journal=Icarus|year=2003|volume=169|issue=2|pages=324–340|