Difference between revisions of "How are features on Mars Named?"

m |

Suitupshowup (talk | contribs) m (→External links) |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

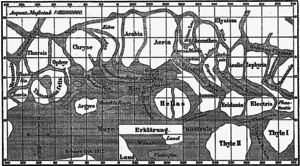

[[File:Karte Mars Schiaparelli MKL1888.png |right|thumb|px| Early Schiaparelli map of Mars with many of the names we use today]] | [[File:Karte Mars Schiaparelli MKL1888.png |right|thumb|px| Early Schiaparelli map of Mars with many of the names we use today]] | ||

| − | Before Schiaparelli published his map with names, other astronomers had done the same. The first map was published in 1840 by Johann Heinrich Mädler and Wilhelm Beer | + | Before Schiaparelli published his map with names, other astronomers had done the same. The first map was published in 1840 by Johann Heinrich Mädler and Wilhelm Beer, but it was not very exciting. Mädler and Beer simply labelled the features a, b, c ... without giving them names. |

The first astronomer to name Martian albedo features systematically was Richard A. Proctor, who in 1867 created a map (based in part on the work of William Rutter Dawes) in which several features were given the names of astronomers who had been involved in mapping Mars. In some cases, the same names were used for multiple features and more of the names came from Proctor’s country of England. <ref>Glasstone, S. 1968. The Book of Mars. NASA. Washington, D.C. </ref> Proctor's names remained in use for several decades, especially in several early maps drawn by Camille Flammarion in 1876 and Nathaniel Everett Green in 1877. | The first astronomer to name Martian albedo features systematically was Richard A. Proctor, who in 1867 created a map (based in part on the work of William Rutter Dawes) in which several features were given the names of astronomers who had been involved in mapping Mars. In some cases, the same names were used for multiple features and more of the names came from Proctor’s country of England. <ref>Glasstone, S. 1968. The Book of Mars. NASA. Washington, D.C. </ref> Proctor's names remained in use for several decades, especially in several early maps drawn by Camille Flammarion in 1876 and Nathaniel Everett Green in 1877. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Syrtis Major quadrangle]] | ||

| + | *[[Tharsis]] | ||

| + | *[[Geography of Mars]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == External links == | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[https://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Page/MARS/target Go here for information on names and locations on Mars -- International Astronomical Union (IAU) Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN)] | ||

===References:=== | ===References:=== | ||

Latest revision as of 04:38, 16 August 2023

Article written by Jim Secosky. Jim is a retired science teacher who has used the Hubble Space Telescope, the Mars Global Surveyor, and HiRISE.

Since Mars has a very thin atmosphere, its surface features can often be seen clearly when Mars is close to the Earth (about every 2 years). As a result, many astronomers had many opportunities to map Mars with telescopes over the years. Some features they observed, like cannels, proved to be illusions when spacecraft returned images of sufficient resolution. Today names of features on Mars are regulated by the International Astronomical Union (IAU). In 1958, it established an ad hoc committee under Audouin Dollfus, which decided on a list of 128 officially, recognized albedo features. Of these, 105 came from Schiaparelli, 2 from Flammarion, 2 from Percival Lowell, and 16 from Antoniadi, with an additional 3 from the committee itself.

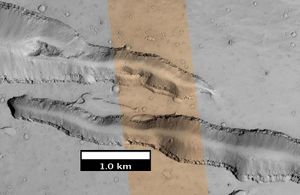

Many features of the planet have a descriptor term attached to the name. Common descriptor terms are Fossa for a linear depression, Mensa for a mesa, and Planitia for a low plain.[1] The pictures returned by interplanetary spacecraft, notably the observations made from Martian orbit by Mariner 9, have revolutionized our understanding of Mars, and some of the classical albedo features have become obsolete as they do not correspond clearly with the detailed images provided by the spacecraft. However, many of the names used for topographic features on Mars are still based on the classical nomenclature for the feature's location; for instance, the albedo feature “Elysium” provides the basis of the name of the volcano Elysium Mons because it is in roughly the same location.

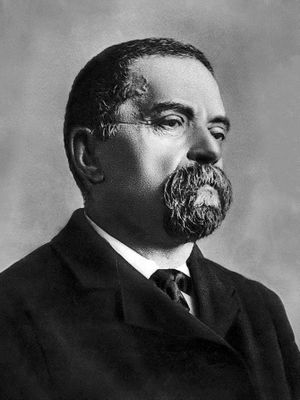

Today, names of Martian features derive from a number of sources, but the names of the large features are derived primarily from the maps of Mars made in 1886 by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli. Schiaparelli named the larger features of Mars primarily using names from Greek mythology and to a lesser extent the Bible. “Tharsis” came from “Of Tharshish and the Isles” in the Bible’s Psalms. “Aeolis” was from the floating island that Homer wrote about. "Ophir" was mentioned as a place to obtain gold for Solomon.[2] “Elysium” was the resting place of the gods. Elysium or the Elysian Fields is an idea of the afterlife that evolved over time and was believed by certain Greek religious and philosophical sects and cults. Initially separate from the realm of Hades, admission was reserved for mortals related to the gods and other heroes. Later, it included those chosen by the gods, the righteous, and the heroic. In the Elysian Fields they would remain after death, to live a blessed and happy life, and indulging in whatever employment they had enjoyed in life.[3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] Schiaparelli was known as the “Father of Mars;” for a whole decade, he knew more about Mars than anyone else in the world.[9] During the planet's "Great Opposition" of 1877, Schiaparelli saw lines on the surface of Mars which he called "canali" in Italian, meaning "channels" but the term was mistranslated into English as "canals".[10] However, there is evidence that he may have thought they were artificial, as Percival Lowell believed.[11] Percival Lowell spent much of his life trying to prove the existence of intelligent life on the red planet.

Before Schiaparelli published his map with names, other astronomers had done the same. The first map was published in 1840 by Johann Heinrich Mädler and Wilhelm Beer, but it was not very exciting. Mädler and Beer simply labelled the features a, b, c ... without giving them names. The first astronomer to name Martian albedo features systematically was Richard A. Proctor, who in 1867 created a map (based in part on the work of William Rutter Dawes) in which several features were given the names of astronomers who had been involved in mapping Mars. In some cases, the same names were used for multiple features and more of the names came from Proctor’s country of England. [12] Proctor's names remained in use for several decades, especially in several early maps drawn by Camille Flammarion in 1876 and Nathaniel Everett Green in 1877.

See also

External links

References:

- ↑ https://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/DescriptorTerms

- ↑ The Life Recovery Bible. 1998. Tyndale House. Wheaton Illinois. 1 Kings 9:28.

- ↑ cite book|last=Peck|first=Harry Thurston|title=Harper's Dictionary of Classical Literature and Antiquities, Volume 1|year=1897|publisher=Harper|location=New York|pages=588, 589|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RacKAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover

- ↑ cite book|last=Sacks|first=David|title=A Dictionary of the Ancient Greek World|year=1997|publisher=Oxford University Press US|isbn=0-19-511206-7|pages=8, 9

- ↑ cite book|last=Zaidman|first=Louise Bruit|title=Religion in the Ancient Greek City|year=1992|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=United Kingdom|isbn=0-521-42357-0|page=78

- ↑ cite book|last=Clare|first=Israel Smith|title=Library of Universal History, Volume 2: Ancient Oriental Nations and Greece|year=1897|publisher=R. S. Peale, J. A. Hill|location=New York

- ↑ cite book|last=Petrisko|first=Thomas W.|title=Inside Heaven and Hell: What History, Theology and the Mystics Tell Us About the Afterlife|year=2000|publisher=St. Andrews Productions|location=McKees Rocks, PA|isbn=1-891903-23-3|pages=12–14

- ↑ cite book|last=Ogden|first=Daniel|title=A Companion to Greek Religion|year=2007|publisher=Blackwell Publishing|location=Singapore|isbn=1-4051-2054-1|pages=92, 93

- ↑ Macdonald, T. 1971. The origins of Martian Nomenclature. Icarus: 15, 233-240.

- ↑ Washam, Erik, "Cosmic Errors: Martians Build Canals!", Smithsonian magazine, December 2010.

- ↑ Glasstone, S. 1968. The Book of Mars. NASA. Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Glasstone, S. 1968. The Book of Mars. NASA. Washington, D.C.