Sublimation landscapes on Mars

Sublimation is the process where a solid goes directly to a gas. It is easily seen with dry ice on Earth. A chunk of dry ice on the Earth will just disappear without leaving any trace of a liquid. Due to the thin atmosphere and extreme cold on Mars, sublimation is very significant in changing water ice to water vapor. It is believed that much of the ground on Mars contains a great deal of ice. Dust is also present in varying amounts with the ice. There is much evidence that the Red Planet once held much water. It probably had streams, rivers, lakes, and perhaps an ocean. Today, nearly all water ice is frozen at the poles or in the ground. Many areas contain much ice that has been preserved for millions of years beneath a cover of dust and other debris. If cracks occur, ice sublimates along the surface. Any dust remaining will eventually be blown away by the wind. The resulting surface will then display various low spots, cracks, and canyons.

Contents

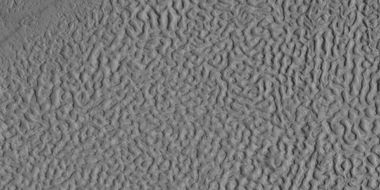

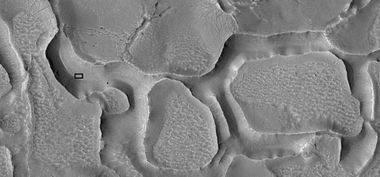

Brain Terrain

Today, most of the water has left the planet, but a substantial amount is left frozen the ground and in a material called “latitude dependent mantle.” After cracks form in the frozen ground and mantle, the fun begins. The cracks greatly increase the surface area over which water can sublimate. Water sublimates and leaves behind dust. The dust insulates the ground below from losing more water for a time or, at times the dust can be blown away. This process creates various holes and pits on the surface. A common feature in ice-rich ground is “brain terrain.” So named for its resemblance to the human brain. Sublimation is greatly increased along the surface of cracks.[1] In time, some broad ridges are left which may still contain some water-ice. The cracks form random patterns So the high and low points are random, thus looking like the outside of our brains. Initially the ridges are wide making what’s called “closed brain terrain;” later when ice leaves the core of the wide ridges, “open brain terrain” results.[2]

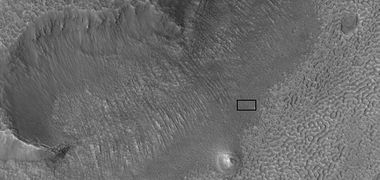

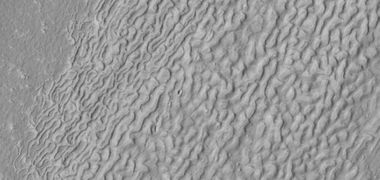

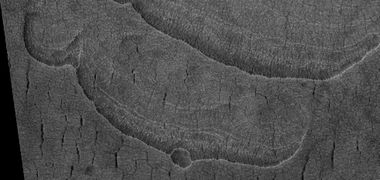

Ribbed Terrain

Sometimes large amounts of ice leave along the cracks and the cracks are bigger, but less in number. Eventually, wide canyons appear. This forms what has been called “ribbed terrain.”[3] A wide version of this sometimes forms wide canyons where the ground seems to be hollowed out. These places can be very beautiful.

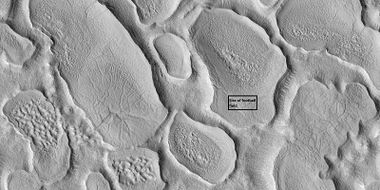

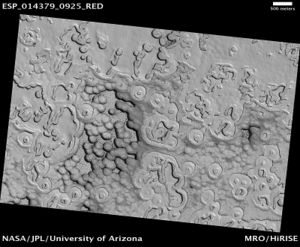

Scalloped Terrain

Another form that develops in ice-rich ground, especially in the higher latitudes is what’s called “scalloped terrain.” It looks like material has been scooped out. Usually scalloped depressions have a steeper pole-facing wall and a gentle equator facing slope.[4]

Seasonal Changes

During the Martian winter dry ice is deposited at the winter pole. During the Martian summer carbon dioxide ice sublimes from the summer pole. The amount that is deposited and then sublimated in the spring is huge—indeed at least 12-16 % of the atmosphere is deposited and removed each Martian year.[5] [6] This process causes great pressure changes and high winds.

Spiders

In places at the southern pole, a thick slab of transparent dry ice covers the ground.[7] With the arrival of higher sunlight levels, much sublimation occurs under the slab and builds up pressure. When cracks appear in weak areas, the gas rushes out at high speeds carrying black dust with it. Speeds may be up to 100 miles per hour.[8] These events can resemble terrestrial geysers. Often surface winds spread the black dust into a fan shaped plume. Under the ice, channels frequently form which looks like a spider, so they are named “spiders.”

Swiss Cheese Terrain

Also, in the southern area, “Swiss Cheese Terrain” develops. Pits form in a 1-10 meter thick layer of dry ice. They get larger and larger in are until the surface looks like Swiss cheese. They start along small fractures.[9] [10] [11] [12] [13]

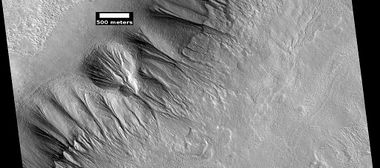

Gullies

In mid-latitudes, gullies are common in large areas in both the northern and southern hemisphere. They occur on steep slopes like crater walls.[14] [15] For many years, they were thought to be caused by running water. However, closer examination over a period of years, revealed that some are growing under present conditions where liquid water is not possible.[16] Experiments on Earth demonstrated that chunks of dry ice moving down slopes could create gullies with a similar appearance. So, at least some of the gullies are being formed by dry ice building up in the winter and then causing erosion as they slide downhill in the warm spring.[17] [18] [19] This process is aided by carbon dioxide vapor jetting off the dry ice and lifting it a bit.[20] Note that present growth of gullies happens just as the temperature rises to where dry ice can easily sublimate.

See also

- High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE)

- Martian features that are signs of water ice

- What Mars Actually Looks Like!

- Sublimation

References

- ↑ Mangold, N (2003). "Geomorphic analysis of lobate debris aprons on Mars at Mars Orbiter Camera scale: Evidence for ice sublimation initiated by fractures." J. Geophys. Res. 108: 8021.

- ↑ Levy, J., J. Head, D. Marchant. 2009. Concentric crater fill in Utopia Planitia: History and interaction between glacial “brain terrain” and periglacial mantle processes. Icarus 202, 462–476.

- ↑ Baker, D., J. Head. 2015. Extensive Middle Amazonian mantling of debris aprons and plains in Deuteronilus Mensae, Mars: Implication for the record of mid-latitude glaciation. Icarus: 260, 269-288.

- ↑ Lefort, A.; Russell, P. S.; Thomas, N.; McEwen, A. S.; Dundas, C. M.; Kirk, R. L. (2009). "Observations of periglacial landforms in Utopia Planitia with the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE)". Journal of Geophysical Research. 114 (E4)

- ↑ Antonio Genova, Sander Goossens, Frank G. Lemoine, Erwan Mazarico, Gregory A. Neumann, David E. Smith, Maria T. Zuber. Seasonal and static gravity field of Mars from MGS, Mars Odyssey and MRO radio science. Icarus, 2016; 272: 228 DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.02.05

- ↑ NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. "New gravity map gives best view yet inside Mars." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 21 March 2016.

- ↑ Portyankina, G., et al. 2018. Laboratory investigations of the physical state of CO2 ice in a simulated Martian environment. Icarus

- ↑ http://themis.asu.edu/news/gas-jets-spawn-dark-spiders-and-spots-mars-icecap

- ↑ Thomas,P., M. Malin, P. James, B. Cantor, R. Williams, P. Gierasch South polar residual cap of Mars: features, stratigraphy, and changes Icarus, 174 (2 SPEC. ISS.). 2005. pp. 535–559. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2004.07.028

- ↑ Thomas, P., P. James, W. Calvin, R. Haberle, M. Malin. 2009. Residual south polar cap of Mars: stratigraphy, history, and implications of recent changes Icarus: 203, 352–375 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2009.05.014

- ↑ Thomas, P., W.Calvin, P. Gierasch, R. Haberle, P. James, S. Sholes. 2013. Time scales of erosion and deposition recorded in the residual south polar cap of mars Icarus: 225: 923–932 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2012.08.038

- ↑ Thomas, P., W. Calvin, B. Cantor, R. Haberle, P. James, S. Lee. 2016. Mass balance of Mars’ residual south polar cap from CTX images and other data Icarus: 268, 118–130 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2015.12.03

- ↑ Buhler, Peter, Andrew Ingersoll, Bethany Ehlmann, Caleb Fassett, James Head. 2017. How the martian residual south polar cap develops quasi-circular and heart-shaped pits, troughs, and moats. Icarus: 286, 69-9.

- ↑ Malin, M.; Edgett, K. (2000). "Evidence for recent groundwater seepage and surface runoff on Mars". Science. 288: 2330–2335

- ↑ Edgett, K.; et al. (2003). "Polar-and middle-latitude martian gullies: A view from MGS MOC after 2 Mars years in the mapping orbit" (PDF). Lunar Planet. Sci. 34. Abstract 1038.

- ↑ https://scitechdaily.com/linear-gullies-on-mars-caused-by-sliding-dry-ice

- ↑ http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/Aug03/MartianGullies.html

- ↑ Diniega, S.; Byrne, S.; Bridges, N. T.; Dundas, C. M.; McEwen, A. S. (2010). "Seasonality of present-day Martian dune-gully activity". Geology. 38: 1047–1050.

- ↑ NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "Study links fresh Mars gullies to carbon dioxide." ScienceDaily 30 October 2010. 10 March 2011

- ↑ https://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2013/jun/HQ_13-180_Mars_Dry_Ice_Gullies.html#.WXDOT4WcGUk