Arabia quadrangle

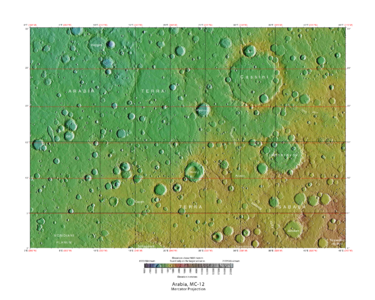

| MC-12 | Arabia | 0–30° N | 0–45° E | Quadrangles | Atlas |

The Arabia quadrangle has some beautiful exposures of layered rocks. On the Earth we flock to our National Parks, like the Grand Canyon, to see similar groups of layered rocks. Dark slope streaks, features unknown on Earth, are common in this area.

The quadrangles of Mars are rectangles of certain areas. Early astronomers looked through telescopes and saw markings on the surface that were subsequently named. Today, we name the quadrangles after old classical regions that are nearby. The Arabia quadrangle contains part of the classic area of Mars known as Arabia Terra. It also contains a part of Terra Sabaea and a small part of Meridiani Planum. It lies on the boundary between the young northern plains and the old southern highlands.

The quadrangle covers the area from 0° to 30° north latitude and 315° to 360° west longitude (45-0 E). Its name of course is after our Earth’s Arabia.

In this article, some of the best pictures from a number of spacecraft will show what the landscape looks like in this region. The origins and significance of all features will be explained as they are currently understood.

Contents

Description

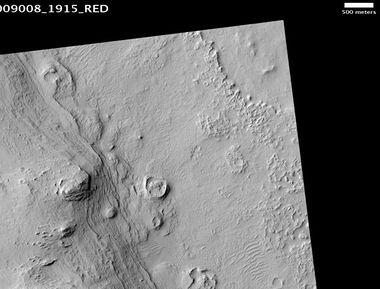

The surface of the Arabia quadrangle appears to be very old because it has a high density of craters, but it is not near as high in elevation as typical old surfaces. The southern hemisphere of Mars is the oldest part of the planet. It is also the highest in elevation. On Mars the oldest areas contain the most craters; the oldest period is called Noachian after the Noachis quadrangle.[1] The Arabia area contains many buttes, mesas, and ridges. Some believe that during certain climate changes an ice-dust layer was deposited; later, parts were eroded to form buttes and mesas.[2] Some outflow channels are found in Arabia, namely Naktong Vallis, Locras Valles, Indus Vallis, Scamander Vallis, and Cusus Valles.[3] This article will show many pictures of these features.

Layers

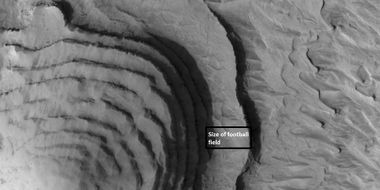

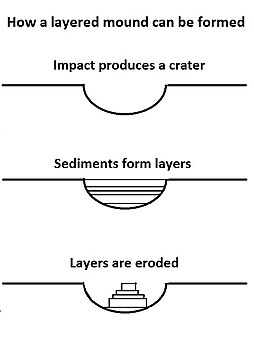

Many places in Arabia are shaped into layers.[4] The layers can be a few meters thick or tens of meters thick. Recent research on these layers by scientists at California Institute of Technology (Caltech) suggest that ancient climate change on Mars caused by regular variation in the planet's tilt, or obliquity may have caused patterns in the layers. On Earth, similar changes (astronomical forcing) of climate results in ice-age cycles.

In places huge numbers of layers are visible. Scientists have found patterns in the arrangement of layers in some locations. A recent study of layers in craters in western Arabia revealed much about the history of the layers. The history of the layers is long and complex because the surface is so, so old. Although the craters in this study are just outside the boundary for the Arabia quadrangle the findings would probably apply to the Arabia quadrangle as well. The thickness of each layer may average less than 4 meters in one crater, but 20 meters in another. The pattern of layers measured in Becquerel Crater, suggests that each layer was formed over a period of about 100,000 years. Moreover, every 10 layers were bundled together into larger units. The 10-layer pattern is repeated at least 10 times. So every 10-layer pattern took one-million years to form.

The tilt of the Earth's axis changes by only a little more than 2 degrees; it is stabilized by the relatively large mass of our moon. In contrast Mars's tilt varies by tens of degrees. When the tilt (or obliquity) is low, the poles are the coldest places on the planet, while the equator is the warmest—as on Earth. This causes gases in the atmosphere, like water and carbon dioxide, to migrate pole ward, where they freeze. When the obliquity (tilt) is greater, the poles receive more sunlight, causing those materials to migrate away. When carbon dioxide moves from the poles, the atmospheric pressure increases, causing a difference in the ability of winds to transport and deposit sand. Also, with more water in the atmosphere sand grains may stick and cement together to form layers. This study of the thickness of layers was done using stereo topographic maps obtained by processing data from the high-resolution camera onboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.[5]

Recent research leads scientists to believe that some of the craters in Arabia may have held lakes. Cassini Crater and Tikonravov Crater probably once were full of water since their rims seem to have been breached by water. Both inflow and outflow channels have been observed on their rims. The inflow channel is higher on the crater rim. So water would move into the crater at the higher inflow channel. Water filled up the crater making a lake and then extra water would exit the lake at the lowest point. Each of these lakes would have contained more water than Earth's Lake Baikal, our largest freshwater lake by volume. The watersheds for lakes in Arabia seem to be too small to gather enough water by precipitation alone; therefore it is thought that much of their water came from groundwater.[6]

Another group of researchers proposed groundwater with dissolved minerals came to the surface, especially inside of craters That mineral-rich groundwater helped to form layers by adding minerals (especially sulfate) and cementing sediments. Upon close examination, Arabia layers appear to have a slight tilt. This tilt supports formation with the action of a rising water table. A water table generally follows the topography. Since the layers slope slightly down toward the northwest, the layers may have been created by groundwater, rather than a single large sea that has been suggested by some researchers.

This hypothesis is supported by a groundwater model and by sulfates discovered in a wide area.[7] [8] At first, by examining surface materials with Opportunity Rover, scientists discovered that groundwater had repeatedly risen and deposited sulfates.[9] [10] [11] [12] [13] Later studies with instruments on board the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter showed that the same kinds of materials exist in a large area that included Arabia.[14] So, in summary, research supports the idea that materials (ice, dust) were deposited in craters and in the area around the craters. Later, groundwater enriched with minerals rose up into those deposits and cemented them. Years later, erosion removed much of these deposits; however in certain spots, like craters, layered deposits were protected. Today, we see layers where they were protected from erosion.

Layers and faults in Arabia quadrangle--HiRISE Picture of the Day (September 25, 2021)

Close view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Box shows the size of a football field.

Light-toned materials

Certain areas of Mars show ground that has a much lighter-tone than most other areas. Much of the surface of Mars is dark because of extensive flows of the dark lave rock basalt. Studies with spectroscopes from orbit have shown that many light-toned areas contain hydrated minerals, and/or clay minerals.[15] [16] [17] [18] That means that in order to produce these substances (hydrated minerals, clays), water had to be in this area. In short, light-toned materials are markers for the past presence of water.

Craters

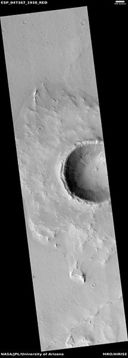

Pedestal craters and layers in Tikonravev Crater in Arabia, as seen by Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) with the Mars Orbiter Camera, under the MOC Public Targeting Program. Layers may form from volcanoes, the wind, or by deposition under water. Some researchers believe this crater once held a massive lake.

Impact craters generally have a rim with ejecta around them, in contrast volcanic craters usually do not have a rim or ejecta deposits. Sometimes craters display layers in their walls. Since the collision that produces a crater is like a powerful explosion, rocks from deep underground are tossed unto the surface. Hence, craters can show us what lies deep under the surface.

Some craters in Arabia are classified as pedestal craters. A pedestal crater is an impact crater with its ejecta sitting above the surrounding terrain. The ejecta sit on a raised platform. They form when an impact crater ejects material which forms an erosion resistant layer, thus protecting the immediate area from erosion. As a result of this hard covering, the crater and its ejecta become elevated, as erosion removes the softer material beyond the ejecta.[19] Some pedestals have been accurately measured to be hundreds of meters above the surrounding area. This means that hundreds of meters of material were eroded away. Pedestal craters were first observed during the Mariner missions.[20] [21][22]

Based on study of years of HiRISE images, researchers believe over 200 new craters are formed each year on Mars, based on study of years of HiRISE images.[23][24]

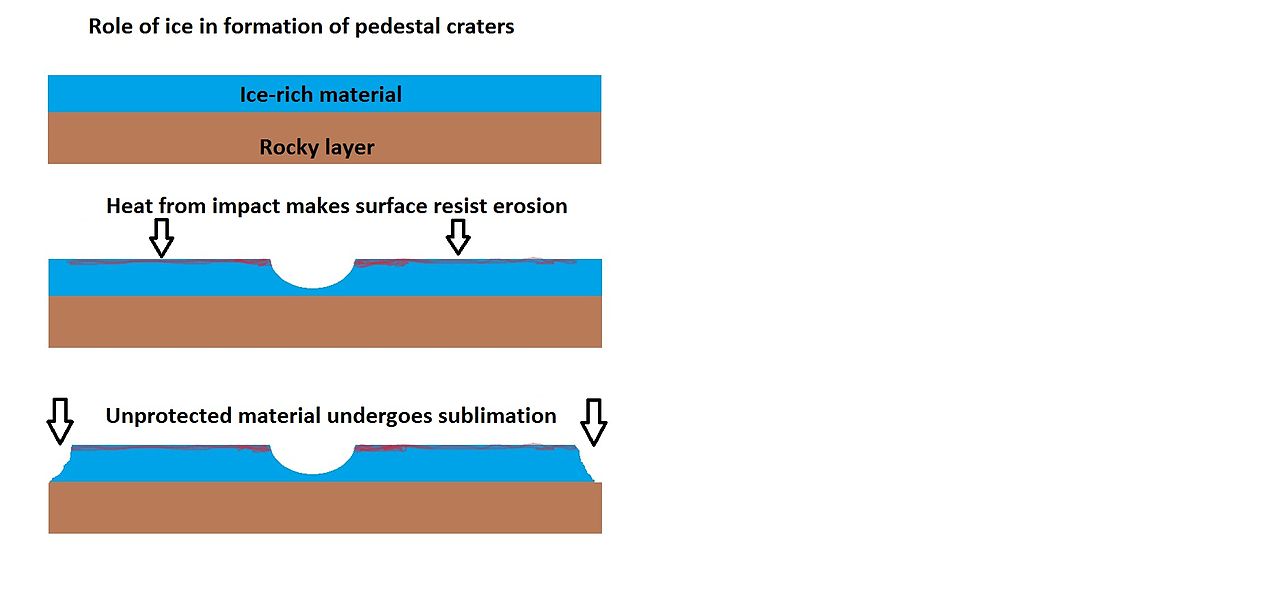

Drawing shows a later idea of how some pedestal craters form. In this way of thinking, an impacting projectile goes into an ice-rich layer—but no further. Heat and wind from the impact hardens the surface against erosion. This hardening can be accomplished by the melting of ice which produces a salt/mineral solution thereby cementing the surface.

Drawing shows a later idea of how some pedestal craters form. In this way of thinking, an impacting projectile goes into an ice-rich layer—but no further. Heat and wind from the impact hardens the surface against erosion. This hardening can be accomplished by the melting of ice which produces a salt/mineral solution thereby cementing the surface.

Northern wall of Teisserenc de Bort Crater showing dark slope streaks, as seen by CTX camera (on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter). Channels are visible. Note this is an enlargement of the previous image.

Close, color view of crater ejecta, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Benches around mounds my mark a former water level. The hot ejecta may have melted ice in the ground forming small channels.

Possible methane

One study with the Planetary Fourier Spectrometer in the Mars Express spacecraft found possible methane in three areas of Mars, one of which was in Arabia. One possible source of methane is from the metabolism of living bacteria.[25] However, a recent study indicates that to match the observations of methane, there must be something that quickly destroys the gas, otherwise it would be spread all through the atmosphere instead of being concentrated in just a few locations. There may be something in the soil that oxidizes the gas before it has a chance to spread. If this is so, that same chemical would destroy organic compounds, thus life would be very difficult on Mars.[26] [27]

Geological history

The Arabia region has been greatly studied by researchers. They have been able to work out a history of this location. The history is quite interesting. Recent studies, reported in the journal Icarus, have suggested that the area underwent several phases in its formation:

- A large basin, maybe from an impact, was produced early in Martian history. It was so early that Mars still had a magnetic field generated by movements in a liquid core. Present day Arabia only possesses remnant magnetism from that ancient era.

- Sediments flowed into the basin. Water entered the basin.

- Because Tharsis, on the other side of Mars, became so massive, the area around Arabia was pushed out. Remember, Tharsis is the place with the largest volcanoes in the solar system. As it bulged upward, there was increased erosion which exposed old layers. When portions of a planet that can be subject to erosion rise, there is greatly increased erosion; Earth's Grand Canyon became very deep because it was eroded into a high plateau.

- Over the following 4 billion years, the area was modified by various geological processes. Central peaks and ejecta shapes indicate that parts of Arabia are still water enriched.[28] [29] [30]

Dark slope streaks

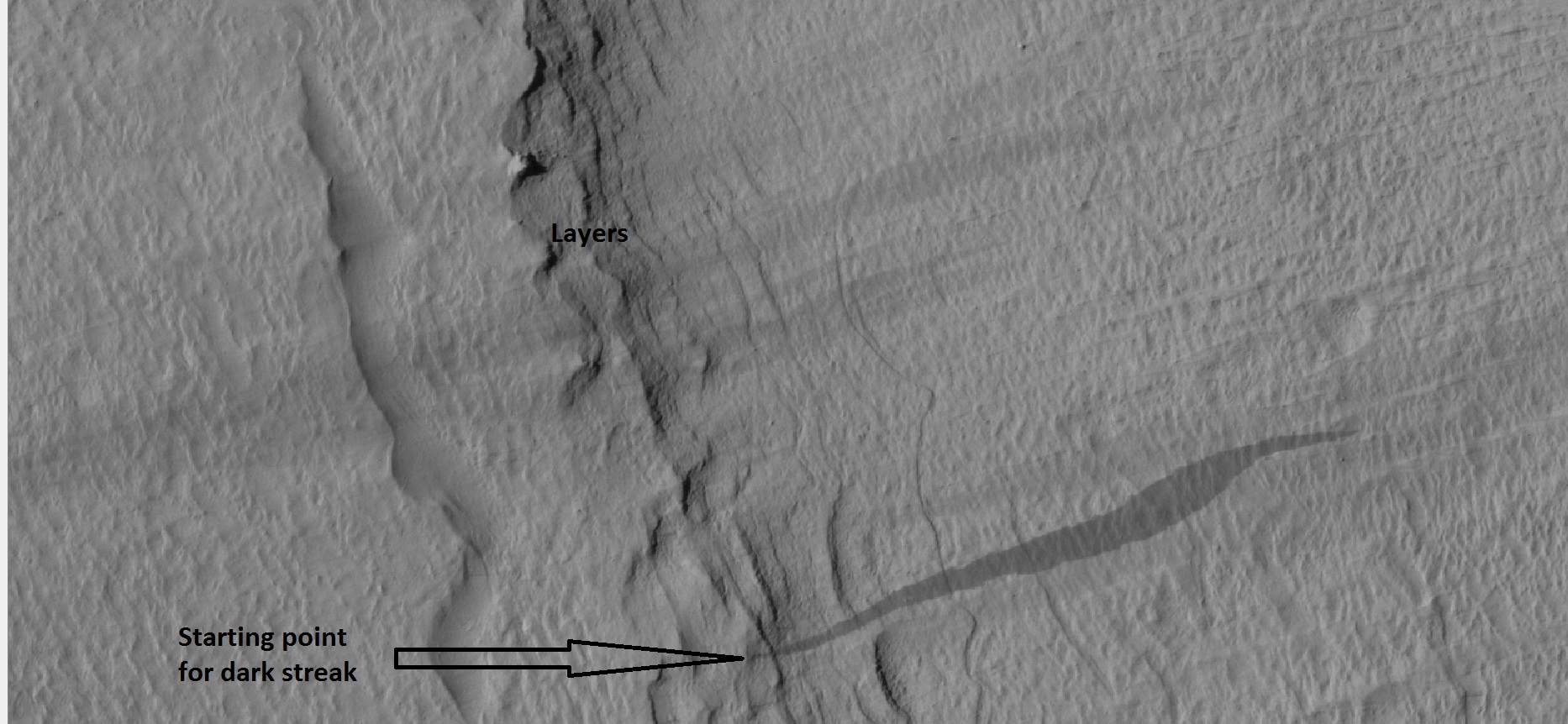

Close-up of some layers under cap rock of a pedestal crater and a dark slope streak The starting point for a streak is often quite small.

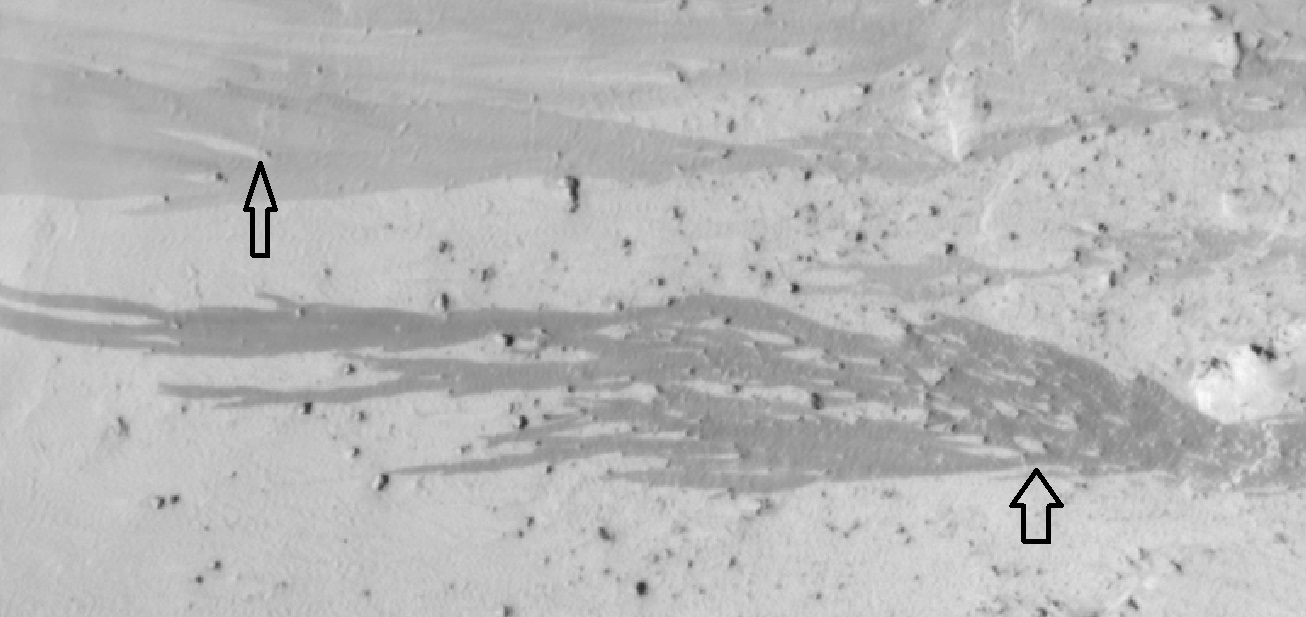

Streaks are common on Mars. They occur on steep slopes of craters, troughs, and valleys. The streaks are dark at first. They get lighter with age.[31] Sometimes they start in a tiny spot, then spread out and go for hundreds of meters. They have been seen to travel around obstacles, like boulders.[32] It is believed that they are avalanches of bright dust that expose a darker underlying layer. However, several ideas have been advanced to explain them. Streaks appear in areas covered with dust. Much of the Martian surface is covered with dust. Fine dust settles out of the atmosphere covering everything. We know a lot about this dust because the solar panels of the Mars Rovers got covered with dust, thus reducing the electrical energy. The power of the Rovers has been restored many times by the wind, in the form of dust devils cleaning the panels and boosting the power. So, we know that dust settles from the atmosphere then returns over and over.[33] Dust storms are frequent, especially when the spring season begins in the southern hemisphere. At that time, Mars is 40% closer to the sun. The orbit of Mars is much more elliptical then the Earth's. That is the difference between the farthest point from the sun and the closest point to the sun is very great for Mars, but only a slight amount for the Earth. Another action that spreads dust on the surface every few years are global dust storms. When NASA's Mariner 9 craft arrived there, nothing could be seen through the dust storm.[34] [35] Other global dust storms have also been observed, since that time.

Research, published in January 2012 in Icarus, found that dark streaks were initiated by airblasts from meteorites traveling at supersonic speeds. The team of scientists was led by Kaylan Burleigh, an undergraduate at the University of Arizona. After counting some 65,000 dark streaks around the impact site of a group of 5 new craters, the team of scientists noted some patterns. The number of streaks was greatest closer to the impact site. So, the impact somehow probably caused the streaks. Also, the distribution of the streaks formed a pattern with two wings extending from the impact site. The curved wings resembled curved knives, called scimitars. This pattern suggests that an interaction of airblasts from the group of meteorites shook dust loose enough to start dust avalanches that formed the many dark streaks. At first it was thought that the shaking of the ground from the impact caused the dust avalanches, but if that was the case the dark streaks would have been arranged symmetrically around the impacts, rather than being concentrated into curved shapes.[36]

Some research suggests that solid carbon dioxide or dry ice is involved in creating these streaks. Dry ice accumulates just under the surface during cold Martian nights and then changes to a gas in the morning. That gas creates enough wind to disturb dust particles and send them down steep slopes. As the bright dust slides down it reveals the underlying dark volcanic rocks. This process was discovered by measuring temperatures in the area. At the recorded temperatures, carbon dioxide from the air should have frozen on the surface, but it was not visible. It was concluded that the dry ice was forming just under the surface rather than on top.[37] [38][39]

Dark slope streaks near the top of a pedestal crater, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

Dark slope streaks, as seen by HiRISE Arrows show how boulders affected the shape of the streaks.

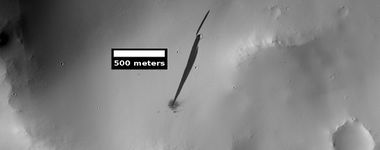

Dark slope streaks can be caused by nearby impacts, as seen in the following HiRISE image of a new small impact that set off a slope streak.

Linear ridge networks and dikes

Linear ridge networks are found in various places on Mars in and around craters.[40] Ridges often appear as mostly straight segments that intersect in a lattice-like manner. They are hundreds of meters long, tens of meters high, and several meters wide. Scientists do not agree on the exact cause of these ridges. One popular idea is that impacts created fractures in the surface, these fractures later acted as channels for fluids. Fluids cemented the structures. With the passage of time, surrounding material was eroded away, thereby leaving hard ridges behind. Since the ridges occur in locations with clay, these formations could serve as a marker for clay which requires water for its formation.[41] [42] [43] Water here could have supported past life in these locations. Clay may also preserve fossils or other traces of past life.

Other landscape features in Arabia quadrangle

Boulders and their tracks from rolling down a slope Arrows show two boulders at the end of their tracks.

Boulders and their tracks from rolling down a slope Arrows show two boulders at the end of their tracks.

Surface cracks Ice-rich ground will produce cracks. Cracks will eventually get larger and larger as ice in the ground leaves due to the process of sublimation (phase transition) in the thin atmosphere of Mars.

Surface cracks Ice-rich ground will produce cracks. Cracks will eventually get larger and larger as ice in the ground leaves due to the process of sublimation (phase transition) in the thin atmosphere of Mars.

Crater, mound, polygons, and layers

See also

- Dark slope streaks

- High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE)

- HiWish program

- How are features on Mars Named?

- Layers on Mars

- Mars Global Surveyor

- Periodic climate changes on Mars

References

- ↑ Dohm J.|display-authors=et al | year = 2007 | title = Possible ancient giant basin and related water enrichment in the Arabia Terra province, Mars | journal = Icarus | volume = 190 | issue = 1| pages = 74–92 | doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.006|

- ↑ Fassett C., Head III | year = 2007 | title = Layered mantling deposits in northeast Arabia Terra, Mars: Noachian-Hesperian sedimentation, erosion, and terrain inversion | journal = Journal of Geophysical Research | volume = 112 | issue = E8| page = 2875 | doi=10.1029/2006je002875|

- ↑ U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey, Topographic Map of the Eastern Region of Mars M 15M 0/270 2AT, 1991

- ↑ Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken (eds.) 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM

- ↑ http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html.pid

- ↑ Fassett, C. and J. Head III. 2008. Valley network-fed, open-basin lakes on Mars: Distribution and implications for Noachian surface and subsurface hydrology. Icarus: 198. 39–56.

- ↑ Andrews-Hanna J. C., Phillips R. J., Zuber M. T. | year = 2007 | title = Meridiani Planum and the global hydrology of Mars | journal = Nature | volume = 446 | issue = 7132| pages = 163–166 | doi = 10.1038/nature05594 |

- ↑ Andrews-Hanna J. C., Zuber M. T., Arvidson R. E., Wiseman S. M. | year = 2010 | title = Early Mars hydrology: Meridiani playa deposits and the sedimentary record of Arabia Terra | url = | journal = J. Geophys. Res. | volume = 115 | issue = | page = E06002 |

- ↑ url=http://marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov/newsroom/pressreleases/20040302a.html%7Ctitle=Opportunity Rover Finds Strong Evidence Meridiani Planum Was Wet|accessdate=8 July 2006| archiveurl= https://web.archive.org/web/20060614061250/http://marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov/newsroom/pressreleases/20040302a.html%7C

- ↑ Grotzinger J. P. | display-authors = etal | year = 2005 | title = Stratigraphy and sedimentology of a dry to wet eolian depositional system, Burns formation, Meridiani Planum, Mars, Earth Planet | url = | journal = Sci. Lett. | volume = 240 | issue = | pages = 11–72 |

- ↑ McLennan S. M. | display-authors = etal | year = 2005 | title = Provenance and diagenesis of the evaporate bearing Burns formation, Meridiani Planum, Mars | url = | journal = Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. | volume = 240 | issue = | pages = 95–121 |

- ↑ Squyres S. W., Knoll A. H. | year = 2005 | title = Sedimentary rocks at Meridiani Planum: Origin, diagenesis, and implications for life on Mars, Earth Planet | url = | journal = Sci. Lett. | volume = 240 | issue = | pages = 1–10 |

- ↑ Squyres S. W.|display-authors=et al | year = 2006 | title = Two years at Meridiani Planum: Results from the Opportunity rover | url = https://eprints.utas.edu.au/2614/1/Science2007.pdf%7C journal = Science | volume = 313 | issue = 5792| pages = 1403–1407 | doi = 10.1126/science |

- ↑ M. Wiseman, J. C. Andrews-Hanna, R. E. Arvidson, J. F. Mustard, K. J. Zabrusky DISTRIBUTION OF HYDRATED SULFATES ACROSS ARABIA TERRA USING CRISM DATA: IMPLICATIONS FOR MARTIAN HYDROLOGY. 42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2011) 2133.pdf

- ↑ Weitz, C. et al. 2017. LIGHT-TONED MATERIALS OF MELAS CHASMA: EVIDENCE FOR THEIR FORMATION ON MARS. Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017) 2794.pdf

- ↑ Weitz C.|display-authors=et al | year = 2015 | title = Mixtures of clays and sulfates within deposits in western Melas Chasma, Mars| journal = Icarus | volume = 251 | pages = 291–314 | doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2014.04.009|

- ↑ Weitz C | year = 2016 | title = Stratigraphy and formation of clays, sulfates, and hydrated silica within a depression in Coprates Catena, Mars| journal = Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets | volume = 121 | issue = 5| pages = 805–835 | doi = 10.1002/2015JE004954 |

- ↑ Bishop J.|display-authors=et al | year = 2013 | title = What the ancient phyllosilicates at Mawrth Vallis can tell us about possible habitability on early Mars | journal = Planetary and Space Science | volume = 86 | pages = 130–149 |

- ↑ hirise.lpl.eduPSP_008508_1870">http://hirise.lpl.eduPSP_008508_1870{{dead link|date=July 2017 |

- ↑ "hirise.lpl.eduPSP_008508_1870"

- ↑ Bleacher, J. and S. Sakimoto. Pedestal Craters, A Tool For Interpreting Geological Histories and Estimating Erosion Rates. LPSC

- ↑ http://themis.asu.edu/feature_utopiacratershttps://web.archive.org/web/20100118173819/http://themis.asu.edu/feature_utopiacraters |

- ↑ http://www.space.com/21198-mars-asteroid-strikes-common.html | title=Pow! Mars Hit by Space Rocks 200 Times a Year

- ↑ http://www.universetoday.com/109020/brand-new-impact-crater-shows-up-on-mars/ |title = Brand New Impact Crater Shows up on Mars|

- ↑ Allen, C., D. Oehler, and E. Venechuk. Prospecting for Methane in Arabia Terra, Mars – First Results. Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVII (2006). 1193.pdf-1193.pdf.

- ↑ http://www.spaceref.com:80/news/viewpr.html?pid=28914 |title=Reconciling Methane Variations on Mars | SpaceRef – Your Space Reference |publisher=Spaceref.com:80 |date=6 August 2009 |

- ↑ http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/mars-methane-gas-disappears-quickly-100920.html |title=Mystery on Mars: Why Methane Fades Away So Fast |publisher=Space.com |date=20 September 2010 |

- ↑ Hartmann, W. 2003. A Traveler's Guide to Mars. Workman Publishing. NY NY.

- ↑ Dohm, J. et al. 2007. Possible ancient giant basin and related water enrichment in the Arabia Terra province, Mars. Icarus: 190. 74–92.

- ↑ Edgett, K. and M. Malin. 2002. Martian sedimentary rock stratigraphy: Outcrops and interbedded craters of northwest Sinus Meridiani and southwest Arabia Terra. Geophysical Research Letters: 29. 32.

- ↑ chorghofer N|display-authors=et al | year = 2007 | title = Three decades of slope streak activity on Mars | journal = Icarus | volume = 191 | issue = 1| pages = 132–140 | doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2007.04.026|

- ↑ http://www.space.com/image_of_day_080730.html

- ↑ https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/02/090217101110.htm |title=Mars Spirit Rover Gets Energy Boost From Cleaner Solar Panels |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=19 February 2009 |

- ↑ Hugh H. Kieffer (1992). Mars. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1257-7.

- ↑ isbn = 978-0-517-00192-9|title = Atlas of the Solar System|last1 = Moore|first1 = Patrick|date = 2 June 1990|url-access = registration|url = https://archive.org/details/atlasofsolarsystem

- ↑ Burleigh Kaylan J., Melosh Henry J., Tornabene Livio L., Ivanov Boris, McEwen Alfred S., Daubar Ingrid J. | year = 2012 | title = Impact air blast triggers dust avalanches on Mars | journal = Icarus | volume = 217 | issue = 1| page = 194 | doi = 10.1016/j.icarus.2011.10.026 |

- ↑ https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2021JE006988

- ↑ Lange, S., et al. 2022. Gardening of the Martian Regolith by Diurnal CO2 Frost and the Formation of Slope Streaks. JGR Planets. Volume127, Issue4. e2021JE006988

- ↑ http://redplanet.asu.edu/ |title = Red Planet Report | What's new with Mars

- ↑ Head, J., J. Mustard. 2006. Breccia dikes and crater-related faults in impact craters on Mars: Erosion and exposure on the floor of a crater 75 km in diameter at the dichotomy boundary, Meteorit. Planet Science: 41, 1675-1690.

- ↑ Mangold |display-authors=et al | year = 2007 | title = Mineralogy of the Nili Fossae region with OMEGA/Mars Express data: 2. Aqueous alteration of the crust | journal = J. Geophys. Res. | volume = 112| issue = E8|pages=E08S04 | doi = 10.1029/2006JE002835 |

- ↑ Mustard et al., 2007. Mineralogy of the Nili Fossae region with OMEGA/Mars Express data: 1. Ancient impact melt in the Isidis Basin and implications for the transition from the Noachian to Hesperian, J. Geophys. Res., 112.

- ↑ Mustard |display-authors=et al | year = 2009 | title = Composition, Morphology, and Stratigraphy of Noachian Crust around the Isidis Basin | journal = J. Geophys. Res. | volume = 114| issue = 7|pages=E00D12 | doi = 10.1029/2009JE003349 |