Difference between revisions of "Radiation shielding"

(Example, and reworded sentence to make it clearer.) |

(Many changes. Main emphasis is that for shot trips, we will accept the dose, but for long term settlements, elaborate protection makes more sense.) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

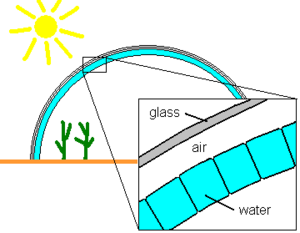

[[Image:WaterShieldGreenhouse.png|thumb|right|300px|Water-shield Greenhouse Concept]] | [[Image:WaterShieldGreenhouse.png|thumb|right|300px|Water-shield Greenhouse Concept]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Early explorers will simply accept the radiation dose for the 3.5 year round trip (which should give approximately a 1% increase of a fatal cancer, from 20 to 21%). (See "The Case for Mars, chapter 5.) However, radiation protection becomes much more of a concern for long durations habitats where people will live on Mars for years or decades. In such cases, thick shielding (of soil or ice), exotic modern materials, or electro-static or magnetic shields become more sensible. Radiation from the natural radioactive elements in the soil should be approximately equal to Earth doses. Radiation from Solar and Cosmic rays will be stronger, with the latter being much more difficult to shield against. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==General== | ||

Shielding against [[radiation]] is considered a very difficult task. For example, a proton or alpha particle cosmic ray of "medium" energy can pass through more than a meter of aluminium, not counting the effects of [[secondary radiation]]<ref name="Logan">''Operational medicine and health care delivery'' - J.S. Logan, in S.E. Churchill ed. ''Fundamentals of space life sciences, Volume 1'' - 1997, ISBN 0-89464-051-8 pp. 154-156.</ref>. With this in mind, it is clear that any Martian colonists would have to take a holistic approach, reducing their radiation exposure at every possible opportunity through shielding and risk-mitigating behaviour. | Shielding against [[radiation]] is considered a very difficult task. For example, a proton or alpha particle cosmic ray of "medium" energy can pass through more than a meter of aluminium, not counting the effects of [[secondary radiation]]<ref name="Logan">''Operational medicine and health care delivery'' - J.S. Logan, in S.E. Churchill ed. ''Fundamentals of space life sciences, Volume 1'' - 1997, ISBN 0-89464-051-8 pp. 154-156.</ref>. With this in mind, it is clear that any Martian colonists would have to take a holistic approach, reducing their radiation exposure at every possible opportunity through shielding and risk-mitigating behaviour. | ||

| Line 178: | Line 182: | ||

==Active shielding== | ==Active shielding== | ||

| − | Active shielding against radiation involves a man-made electromagnetic field which deflects ionized particles in a similar manner to the Earth's magnetic field. Several different types of active shield have been proposed, including electric field, magnetic field, and plasma shield designs. Such fields might require infeasible amounts of energy to generate | + | For a Martian stay of 18 months, elaborate precautions are not needed. If people are going to spend many years on Mars, active shielding becomes more important. Active shielding against radiation involves a man-made electromagnetic field which deflects ionized particles in a similar manner to the Earth's magnetic field. Several different types of active shield have been proposed, including electric field, magnetic field, and plasma shield designs. Such fields might require infeasible amounts of energy to generate (a Mars temperature superconductor would be useful here). Such a magnetic shield could also pose a risk to anyone approaching the craft or base, as it would create bands of trapped particles similar to the Van Allen belts.<ref name="Logan" /> However, the radiation exposure might be low, as traversing the magnetic shield should be a very brief event. (If these 'van Allen belts' cross into the ground, charged particles would be absorbed and the issue won't arise. For a fixed base, one pole could be in the air, and one underground.) |

It might be possible to situate a base in such a location that one of the residual Martian magnetic fields offers a net benefit. Care should certainly be taken not to situate it where the fields concentrate radiation. | It might be possible to situate a base in such a location that one of the residual Martian magnetic fields offers a net benefit. Care should certainly be taken not to situate it where the fields concentrate radiation. | ||

| Line 187: | Line 191: | ||

====Protection during transit to Mars==== | ====Protection during transit to Mars==== | ||

| − | A straightforward approach to designing an active shield would be to surround the protected space with a spherical enclosure made of a conducting metal that is held at a positive electric charge. | + | A straightforward approach to designing an active shield would be to surround the protected space with a spherical enclosure made of a conducting metal that is held at a positive electric charge. Solar radiation both consist of positively charged particles, which would be repelled by the positively charged shield. Positively charged cosmic rays have too much energy to be deflected by such a shield. To protect science experiments from cosmic rays on Earth, scientists go deep underground. They do not make a small metal charged dome. |

One drawback to this concept is that the shield would attract free electrons and accelerate them, creating secondary radiation when they impact the shield. These electrons would also drain the shield's positive charge, increasing the power needed to maintain it. | One drawback to this concept is that the shield would attract free electrons and accelerate them, creating secondary radiation when they impact the shield. These electrons would also drain the shield's positive charge, increasing the power needed to maintain it. | ||

| Line 198: | Line 202: | ||

A 2012 paper by Westover et al. described a design that used a magnetic field. The field could be generated by multiple layers of superconducting material wrapped around a cylindrical spacecraft in double-helix-shaped coils. Their simulations of this design found that a large, weak field was easier to generate than a small, intense field of equivalent shielding effectiveness. They also examined another design, a cylindrical spaceship surrounded by six exterior solenoids, each centered on a separate central axis (unlike the double helix design, in which the magnetic coil and the spacecraft are co-axial). To reduce the magnetic field inside the spacecraft, a compensation coil, with a current moving in the opposite direction, would surround it. Overall this design was judged to be preferable to the double helix design. Shortcomings of the latter design include the fact that the multiple layers of coils make it difficult to design a shield that can be compacted for launch and later expanded in space. In addition, it would be more difficult to block the magnetic field intruding into the spacecraft because the field strength varies more at different points within the spacecraft; problems might also arise from forces created by the magnetic field acting on the shield or spacecraft.<ref>Westover SC, Meinke RB, BurgerWJ, Van Sciver S, Washburn S, et al. 2012. Magnet Architectures and Active Radiation Shielding Study. <nowiki>https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20190002579</nowiki></ref> | A 2012 paper by Westover et al. described a design that used a magnetic field. The field could be generated by multiple layers of superconducting material wrapped around a cylindrical spacecraft in double-helix-shaped coils. Their simulations of this design found that a large, weak field was easier to generate than a small, intense field of equivalent shielding effectiveness. They also examined another design, a cylindrical spaceship surrounded by six exterior solenoids, each centered on a separate central axis (unlike the double helix design, in which the magnetic coil and the spacecraft are co-axial). To reduce the magnetic field inside the spacecraft, a compensation coil, with a current moving in the opposite direction, would surround it. Overall this design was judged to be preferable to the double helix design. Shortcomings of the latter design include the fact that the multiple layers of coils make it difficult to design a shield that can be compacted for launch and later expanded in space. In addition, it would be more difficult to block the magnetic field intruding into the spacecraft because the field strength varies more at different points within the spacecraft; problems might also arise from forces created by the magnetic field acting on the shield or spacecraft.<ref>Westover SC, Meinke RB, BurgerWJ, Van Sciver S, Washburn S, et al. 2012. Magnet Architectures and Active Radiation Shielding Study. <nowiki>https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20190002579</nowiki></ref> | ||

| + | |||

==== Minimagnetosphere ==== | ==== Minimagnetosphere ==== | ||

| − | A minimagnetosphere<ref>https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325285302_Can_artificial_miniature_magnetospheres_be_used_to_protect_spacecraft</ref> may be a viable alternative to the strong local magnetic fields described above. Minimagnetospheres have been detected on the Moon<ref>https://www.universetoday.com/79781/moons-mini-magnetosphere/</ref>, and indications show that they have modified the interactions of the solar wind with the surface. The concept uses an electric field rather than the magnetic field. An plasma cloud is created around the vehicle by injecting charged particles and kept in place using a small superconducting magnet at the vehicle. The electrical charge can deflect particles due to the large size on the minimagnetosphere, that can reach a number of km in diameter. This solution might be particularly applicable to a cycler type vehicle. | + | A minimagnetosphere<ref>https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325285302_Can_artificial_miniature_magnetospheres_be_used_to_protect_spacecraft</ref> may be a viable alternative to the strong local magnetic fields described above for spacecraft. Minimagnetospheres have been detected on the Moon<ref>https://www.universetoday.com/79781/moons-mini-magnetosphere/</ref>, and indications show that they have modified the interactions of the solar wind with the surface. The concept uses an electric field rather than the magnetic field. An plasma cloud is created around the vehicle by injecting charged particles and kept in place using a small superconducting magnet at the vehicle. The electrical charge can deflect particles due to the large size on the minimagnetosphere, that can reach a number of km in diameter. This solution might be particularly applicable to a cycler type vehicle. |

| + | |||

| + | The mass required to generate such a mini-magnetosphere must be low, or people will do without and accept the modest radiation exposure for such a trip. | ||

==Risk-mitigating behavior== | ==Risk-mitigating behavior== | ||

| − | The possible sources of radiation on Mars are man-made sources, such as nuclear reactors or medical equipment, [[solar radiation]], [[galactic cosmic radiation]] and naturally occurring [[radioactive elements]] on Mars. | + | The possible sources of radiation on Mars are man-made sources, (such as nuclear reactors or medical equipment), [[solar radiation]], [[galactic cosmic radiation]] and naturally occurring [[radioactive elements]] on Mars. |

Possible behavioral choices which minimize the risk from these include: | Possible behavioral choices which minimize the risk from these include: | ||

| Line 210: | Line 217: | ||

*Working preferentially close to natural or man-made objects, such as habitats, rovers or cliffs which provide additional (if not omni-directional) shielding. For example, if a base was at the base of a tall cliff, then half of the surface cosmic rays, and half the high energy solar radiation would be shielded from. | *Working preferentially close to natural or man-made objects, such as habitats, rovers or cliffs which provide additional (if not omni-directional) shielding. For example, if a base was at the base of a tall cliff, then half of the surface cosmic rays, and half the high energy solar radiation would be shielded from. | ||

*Entering a [[storm shelter]] when there is a high-radiation risk from [[solar particle event|solar particle events]]. | *Entering a [[storm shelter]] when there is a high-radiation risk from [[solar particle event|solar particle events]]. | ||

| + | *Placing blocks of ice around the outer walls of the base is an excellent radiation shield. Sandbags on the roof of the habitat provide excellent solar protection, and very minor protection verses cosmic rays. | ||

==Example of using shielding and behavior to reduce radiation dosage== | ==Example of using shielding and behavior to reduce radiation dosage== | ||

| Line 226: | Line 234: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | "The Case For Mars", by Robert Zubrin, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-1-4516-0811-3. Chapter 5 has a very nice breakdown of radiation exposure from Conjunction and Opposition class missions. | ||

| + | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Radiation Protection]] | [[Category:Radiation Protection]] | ||

Revision as of 13:11, 24 May 2022

Early explorers will simply accept the radiation dose for the 3.5 year round trip (which should give approximately a 1% increase of a fatal cancer, from 20 to 21%). (See "The Case for Mars, chapter 5.) However, radiation protection becomes much more of a concern for long durations habitats where people will live on Mars for years or decades. In such cases, thick shielding (of soil or ice), exotic modern materials, or electro-static or magnetic shields become more sensible. Radiation from the natural radioactive elements in the soil should be approximately equal to Earth doses. Radiation from Solar and Cosmic rays will be stronger, with the latter being much more difficult to shield against.

Contents

General

Shielding against radiation is considered a very difficult task. For example, a proton or alpha particle cosmic ray of "medium" energy can pass through more than a meter of aluminium, not counting the effects of secondary radiation[1]. With this in mind, it is clear that any Martian colonists would have to take a holistic approach, reducing their radiation exposure at every possible opportunity through shielding and risk-mitigating behaviour.

Passive shielding

In most cases, matter placed between a person (or radiation-sensitive equipment) and radiation source reduces the amount of radiation they absorb.

Mars One's solution is a thick layer of regolith on top of the settlement modules. An effective shield will require at least several hundred grams of regolith per square centimeter, according to one study.[2] Using a regolith density estimate of 1.4 g/cm3[3], this means the regolith layer would need to be over 2 meters deep. For concrete with an average density of 2.4 g/cm3 the required thickness might be less.

Protection from Electromagnetic Radiation

The attenuation of radiation follows the Beer Lamberth law.[4]

Ix=Io*e-ux

| Where: | Ix | = | the intensity of photons transmitted across some distance x |

| I0 | = | the initial intensity of photons (or radiation in general) | |

| s | = | a proportionality constant that reflects the total probability of a photon being scattered or absorbed (TBC) | |

| µ | = | the linear attenuation coefficient | |

| x | = | distance traveled (thickness of material) |

| Absorber | 100 keV | 200 keV | 500 keV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air | 0.000195 | 0.000159 | 0.000112 |

| Water | 0.167 | 0.136 | 0.097 |

| Carbon | 0.335 | 0.274 | 0.196 |

| Aluminium | 0.435 | 0.324 | 0.227 |

| Iron | 2.72 | 1.09 | 0.655 |

| Copper | 3.8 | 1.309 | 0.73 |

| Lead | 59.7 | 10.15 | 1.64 |

the linear attenuation coefficient µ is not commonly found in the literature, the mass attenuation coefficient µm is usually used instead. The coefficient is also dependent on the type of radiation, so a complete solution for radiation protection requires multiple analysis of the type of radiation to be protected against.

Conversion is quite simple as:

µ=µm*density of the material

List of mass attenuation coefficients[6] can be found at the NIST website. https://physics.nist.gov/PhysRefData/XrayMassCoef/tab3.html

Another common way of evaluating radiation shielding is to use the half value, that expresses the thickness of absorbing material which is needed to reduce the incident radiation intensity by a factor of two, or Ix=Io / 2.

The Half Value Layer for a range of absorbers is listed in the following table for three gamma-ray energies:

| Absorber | 100 keV | 200 keV | 500 keV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air | 3555 | 4359 | 6189 |

| Water | 4.15 | 5.1 | 7.15 |

| Carbon | 2.07 | 2.53 | 3.54 |

| Aluminium | 1.59 | 2.14 | 3.05 |

| Iron | 0.26 | 0.64 | 1.06 |

| Copper | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.95 |

| Lead | 0.012 | 0.068 | 0.42 |

The first point to note is that the Half Value Layer decreases as the atomic number increases. For example, the value for air at 100 keV is about 35 meters and it decreases to just 0.12 mm for lead at this energy. In other words 35 m of air is needed to reduce the intensity of a 100 keV gamma-ray beam by a factor of two whereas just 0.12 mm of lead can do the same thing. The Half Value Layer increases with increasing gamma-ray energy. For example, from 0.18 cm for copper at 100 keV to about 1 cm at 500 keV.

Protection from Particulate Radiation

On Earth, particulate radiation is often easily addressed because the particles have low enough energies that they can be stopped by a thin shield. In space and on the surface of Mars, shielding needs to account for high-energy particles. When it comes to particulate radiation, the effectiveness of shielding increases with the mass of the shielding and decreases with the atomic mass of the elements used for the shielding. The reason that low-atomic-mass elements are advantageous is that they generate less secondary radiation when impacted by particles.[7] For example, 1kg of hydrogen offers more protection then 1kg of aluminium, 2kg of aluminium offers more protection than 1kg of aluminium and 1kg of hydrogen offers more protection than 2kg of aluminium.[8] Also, particles interact with atomic nuclei, while electromagnetic radiation interacts with electrons. So while for electromagnetic radiations the effectiveness of shielding increases with the number of electrons, and therefore with heavier atoms that have more electrons, for particles the effectiveness of radiation protection increases with the number of nuclei per volume, and lighter materials such as hydrogen have more nuclei per volume.

Possible Shielding Materials

| Material | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Metal | Efficiency of using structural material for incidental shielding benefit; some metals block EM radiation very well | Secondary radiation[9] |

| Plastic | High hydrogen content[9] | Less structural utility than metal |

| Water | High hydrogen content[9] | Liquid |

| Liquid hydrogen | Pure hydrogen | Cryogenic liquid |

| Regolith | Obtainable through ISRU | Large thickness required for thorough shielding[10] |

| Regolith plus epoxy | Mostly obtainable through ISRU; greater hydrogen content than regolith alone; more durable and easier to shape than regolith alone[3] | More complex to implement than regolith alone |

| Boron nitride nanotubes | Low atomic numbers; boron absorbs secondary neutrons well compared to other elements; possible use as both shielding and structural material[11]; hydrogen could be stored in or bonded to nanotubes to improve shielding[12] | Difficult to manufacture |

Active shielding

For a Martian stay of 18 months, elaborate precautions are not needed. If people are going to spend many years on Mars, active shielding becomes more important. Active shielding against radiation involves a man-made electromagnetic field which deflects ionized particles in a similar manner to the Earth's magnetic field. Several different types of active shield have been proposed, including electric field, magnetic field, and plasma shield designs. Such fields might require infeasible amounts of energy to generate (a Mars temperature superconductor would be useful here). Such a magnetic shield could also pose a risk to anyone approaching the craft or base, as it would create bands of trapped particles similar to the Van Allen belts.[1] However, the radiation exposure might be low, as traversing the magnetic shield should be a very brief event. (If these 'van Allen belts' cross into the ground, charged particles would be absorbed and the issue won't arise. For a fixed base, one pole could be in the air, and one underground.)

It might be possible to situate a base in such a location that one of the residual Martian magnetic fields offers a net benefit. Care should certainly be taken not to situate it where the fields concentrate radiation.

Also, it might be possible (assuming one could generate the required magnetic field in some way) to have the radiation belts of the habitat pass through some sort of physical barrier, which scrubs them of particles.

Design concepts

Protection during transit to Mars

A straightforward approach to designing an active shield would be to surround the protected space with a spherical enclosure made of a conducting metal that is held at a positive electric charge. Solar radiation both consist of positively charged particles, which would be repelled by the positively charged shield. Positively charged cosmic rays have too much energy to be deflected by such a shield. To protect science experiments from cosmic rays on Earth, scientists go deep underground. They do not make a small metal charged dome.

One drawback to this concept is that the shield would attract free electrons and accelerate them, creating secondary radiation when they impact the shield. These electrons would also drain the shield's positive charge, increasing the power needed to maintain it.

This led to the idea of adding a negatively-charged outer shield to keep electrons away from the positively-charged inner shield. However, this introduces its own problems: the mass requirement increases substantially, and the two shields must be tightly fixed in precise concentric positions, because any asymmetry would result in a strong attractive force that would pull the two shields together.

More recent concepts have moved away from the idea of enclosing the protected space in a charged shell. A 2006 paper described a design in which trusses extended out from a spacecraft in the x, y, and z directions. The trusses are used to suspend individual sphere-shaped charge centers: positive charges are held 50 m from the spacecraft, and negative charges are 160 m out. These charges are meant to generate an electric field sufficient to deflect incoming ions approaching from any direction. Despite the elimination of the enclosing shells, the authors concluded that the mass requirement was still too high for this design to be practical.[13]

In 2011, a concept using toroidal (doughnut-shaped) rings as charge centers was studied. Three conductive rings, each with a 45 m radius, are positioned with their axes of symmetry along the x, y, and z axes, and held at a positive voltage. In addition, six negatively-charged spheres are suspended from trusses, 160 m out. For comparison, the researchers ran simulations of this design and a similar design that used only spherical charge centers. Both designs offered good protection from SPE. The toroid design was more effective against GCR. Ring thicknesses of 1, 5, and 10 m were simulated, showing effectiveness against GCR increasing as a function of thickness. To minimize the mass of the shield, the use of an electrostatically inflated membrane structure was proposed for the charge centers: instead of using a rigid metal, the charge center surfaces would be made of a flexible membrane with a conductive coating. Unlike a balloon that is inflated by filling it with a gas, this type of structure would inflate to its intended shape when electrically charged because of repulsion between like charges distributed across the membrane.[14]

A 2012 paper by Westover et al. described a design that used a magnetic field. The field could be generated by multiple layers of superconducting material wrapped around a cylindrical spacecraft in double-helix-shaped coils. Their simulations of this design found that a large, weak field was easier to generate than a small, intense field of equivalent shielding effectiveness. They also examined another design, a cylindrical spaceship surrounded by six exterior solenoids, each centered on a separate central axis (unlike the double helix design, in which the magnetic coil and the spacecraft are co-axial). To reduce the magnetic field inside the spacecraft, a compensation coil, with a current moving in the opposite direction, would surround it. Overall this design was judged to be preferable to the double helix design. Shortcomings of the latter design include the fact that the multiple layers of coils make it difficult to design a shield that can be compacted for launch and later expanded in space. In addition, it would be more difficult to block the magnetic field intruding into the spacecraft because the field strength varies more at different points within the spacecraft; problems might also arise from forces created by the magnetic field acting on the shield or spacecraft.[15]

Minimagnetosphere

A minimagnetosphere[16] may be a viable alternative to the strong local magnetic fields described above for spacecraft. Minimagnetospheres have been detected on the Moon[17], and indications show that they have modified the interactions of the solar wind with the surface. The concept uses an electric field rather than the magnetic field. An plasma cloud is created around the vehicle by injecting charged particles and kept in place using a small superconducting magnet at the vehicle. The electrical charge can deflect particles due to the large size on the minimagnetosphere, that can reach a number of km in diameter. This solution might be particularly applicable to a cycler type vehicle.

The mass required to generate such a mini-magnetosphere must be low, or people will do without and accept the modest radiation exposure for such a trip.

Risk-mitigating behavior

The possible sources of radiation on Mars are man-made sources, (such as nuclear reactors or medical equipment), solar radiation, galactic cosmic radiation and naturally occurring radioactive elements on Mars.

Possible behavioral choices which minimize the risk from these include:

- Avoiding daytime EVA during solar storms.

- Working preferentially close to natural or man-made objects, such as habitats, rovers or cliffs which provide additional (if not omni-directional) shielding. For example, if a base was at the base of a tall cliff, then half of the surface cosmic rays, and half the high energy solar radiation would be shielded from.

- Entering a storm shelter when there is a high-radiation risk from solar particle events.

- Placing blocks of ice around the outer walls of the base is an excellent radiation shield. Sandbags on the roof of the habitat provide excellent solar protection, and very minor protection verses cosmic rays.

Example of using shielding and behavior to reduce radiation dosage

We can combine passive shielding with risk mitigating behavior to achieve low radiation exposure but still allow for some views of the exterior through windows. For example:

- Martian background average radiation is 240-300 mSv per year[18].

- If you sleep in a radiation shielded space such as underground rooms with a thick regolith cover, 8/24 hours, then the dose would go down by 1/3, to 160-200 mSv per year.

- If you spend most of your living (work, study) time in a radiation shielded space, then your dose becomes another 1/3 less, or 80 to 100 mSv.

- With overhangs and a radiation proof roof, 70% of the incident radiation to a space close to windows can be stopped by geometries, then the dose is down to 20 to 25 mSv. this is about the 20 mSv per year for a 5 year period that is recommended for radiation workers.

- Part of the surface dose on Mars is solar proton events (SPE). These are predictable and detectable, and a large settlement will mostly be built of shielded areas. So during Solar Proton Events you should stay away from the windows. This behavior might reduce the yearly radiation load another 25%, down to 15-18 mSv per year.

- What is the portion of the dosage from SPE? I have a weak reference that puts this at 30%. If correct, then the radiation load from large windows under a radiation proof ceiling is acceptable.

- Mars should be low in radon because it seems to be low in Thorium and, by analogy, Uranium as well. However, the habitats are totally enclosed spaces and radon generated by radioactive decay of naturally occurring uranium in the soil might accumulate. As 1 to 3 mSv on Earth comes from atmospheric radon[19], this part of the yearly load might go away, just as it might need to be mitigated if radon accumulates in the enclosed habitats.

- Even just 1/2 to 1 inches of glass reduces radiation dosage significantly.

If the above is correct, then large windows are not really an issue. Geodesic glass domes over public spaces might be a poor choice, unless there is an understanding that you don't spend more than 2 to 4 hours per day under them.

References

"The Case For Mars", by Robert Zubrin, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-1-4516-0811-3. Chapter 5 has a very nice breakdown of radiation exposure from Conjunction and Opposition class missions.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Operational medicine and health care delivery - J.S. Logan, in S.E. Churchill ed. Fundamentals of space life sciences, Volume 1 - 1997, ISBN 0-89464-051-8 pp. 154-156.

- ↑ Slaba, T. C., Mertens, C. J., & Blattnig, S. R. (2013). Radiation Shielding Optimization on Mars. NASA/TP–2013-217983. Retrieved from https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20130012456.pdf

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kim, M. Y., Thibeault, S. A., Simonsen, L. C., & Wilson, J. W. Comparison of Martian Meteorites and Martian Regolith as Shield Materials for Galactic Cosmic Rays. NASA TP-1998-208724. Retrieved from https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19980237030.pdf.

- ↑ https://www.nde-ed.org/EducationResources/CommunityCollege/Radiography/Physics/attenuationCoef.htm

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Basic_Physics_of_Nuclear_Medicine/Attenuation_of_Gamma-Rays

- ↑ https://www.nde-ed.org/EducationResources/CommunityCollege/Radiography/Physics/attenuationCoef.htm

- ↑ Wilson JW, Cucinotta FA, Thibeault SA, Kim M, Shinn JL, Badavi FF. Radiation Shielding Design Issues. In *Shielding Strategies for Human Space Exploration* (Chapter 7). http://hdl.handle.net/2060/19980137598

- ↑ Radiation biology - J.R. Letaw, in S.E. Churchill ed. Fundamentals of space life sciences, Volume 1 - 1997, ISBN 0-89464-051-8 pp. 16-17.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Parker LJ. (2016). Human radiation exposure tolerance and expected exposure during colonization of the Moon and Mars. http://www.marspapers.org/paper/Parker_2016_1.pdf

- ↑ James G, Chamitoff G, and Barker D. Resource Utilization and Site Selection for a Self-Sufficient Martian Outpost. NASA/TM-98-206538. http://hdl.handle.net/2060/19980147990

- ↑ Tiano, Amanda L, et al. “Boron Nitride Nanotube: Synthesis and Applications.” NTRS Document ID 20140004051, 2014. http://hdl.handle.net/2060/20140004051

- ↑ Thibeault SA, Fay CC, Lowther SE, Earle KD, Sauti G, Kang JH, Park C, McMullen AM. (2012). Radiation Shielding Materials Containing Hydrogen, Boron, and Nitrogen: Systematic Computational and Experimental Study. Phase I. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20160010096

- ↑ Smith JG, Smith T, Williams M, Youngquist R, and Mendell W. Potential Polymeric Sphere Construction Materials for a Spacecraft Electrostatic Shield. NASA/TM—2006–214302. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20060013423

- ↑ Tripathi RK. 2016. Meeting the Grand Challenge of Protecting Astronauts Health: Electrostatic Active Space Radiation Shielding for Deep Space Missions. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20160010094

- ↑ Westover SC, Meinke RB, BurgerWJ, Van Sciver S, Washburn S, et al. 2012. Magnet Architectures and Active Radiation Shielding Study. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20190002579

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325285302_Can_artificial_miniature_magnetospheres_be_used_to_protect_spacecraft

- ↑ https://www.universetoday.com/79781/moons-mini-magnetosphere/

- ↑ NASA, Tony C. Slaba, Christopher J. Mertens, and Steve R. Blattnig Radiation Shielding Optimization on Mars , https://spaceradiation.larc.nasa.gov/nasapapers/NASA-TP-2013-217983.pdf, Apr 2013.

- ↑ http://nuclearsafety.gc.ca/eng/resources/radiation/introduction-to-radiation/radiation-doses.cfm