Aeolis quadrangle

The Aeolis quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mar] used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Aeolis quadrangle is also referred to as MC-23 (Mars Chart-23).[1] The Aeolis quadrangle covers 180° to 225° W (135 E) and 0° to 30° south on Mars, and contains parts of the regions Elysium Planitia and Terra Cimmeria. A small part of the Medusae Fossae Formation lies in this quadrangle. The name refers to the name of a floating western island of Aiolos, the ruler of the winds. In Homer's account, Odysseus received the west wind Zephyr here and kept it in bags, but the wind got out.[2] It is famous as the site of two spacecraft landings: the Spirit Rover rover landing site (14.5718 S and 175.4785E {184.525 W ) in Gusev crater (January 4, 2004), and the Curiosity Rover rover in Gale Crater (4.591817 S and 137.440247 E {222.55973}) (August 6, 2012).[3]

Contents

Major Features

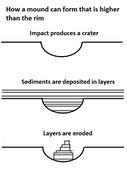

A large, ancient river valley, called Ma'adim Vallis, enters at the south rim of Gusev Crater, so Gusev Crater was believed to be an ancient lake bed. However, it seems that a volcanic flow covered up the lakebed sediments.[4] Apollinaris Patera, a large volcano, lies directly north of Gusev Crater.[5] Gale Crater, in the northwestern part of the Aeolis quadrangle, is of special interest to geologists because it contains a 2–4 km (1.2–2.5 mile) high mound of layered sedimentary rocks, named Aeolis Mons, but later changed to "Mount Sharp" by NASA in honor of Robert P. Sharp (1911–2004), a planetary scientist of early Mars missions.[6] [7] [8] More recently, on 16 May 2012, "Mount Sharp" was officially named Aeolis Mons by the USGS and IAU. [9]

Some regions in the Aeolis quadrangle show inverted relief.[10] In these locations, a stream bed may be a raised feature, instead of a valley. The inverted former stream channels may be caused by the deposition of large rocks or due to cementation. In either case erosion would erode the surrounding land but leave the old channel as a raised ridge because the ridge will be more resistant to erosion

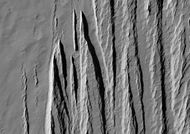

Yardangs are another feature found in this quadrangle They are generally visible as a series of parallel linear ridges, caused by the direction of the prevailing wind.

What we learned from the Spirit Rover

Many forms of evidence from Spirit’s instruments pointed to the past presence of water. Some minerals that were detected had to have water for their formation. Analysis of rock compositions supported the notion that the rocks have been slightly altered by tiny amounts of water. Outside coatings and cracks inside the rocks suggest water deposited minerals (maybe bromine compounds). [11] Spirit’s instruments found that rocks on the plains of Gusev are a type of basalt. They contain the minerals olivine, pyroxene, plagioclase, and magnetite. They look like volcanic basalt as they are fine-grained with irregular holes .[12] [13] Some soils showed fairly high levels of nickel; probably from meteorites.[14] Dust in Gusev Crater was determined to be the same as dust all around the planet. All the dust was magnetic. Since one of the magnets was able to completely divert all the dust, it was concluded that all Martian dust is magnetic.[15] Studies led scientists to conclude that magnetism was caused by the mineral magnetite-- especially magnetite that contained the element titanium. The spectra of the dust was similar to spectra of bright, low thermal inertia regions like Arabia and Tharsis that have been detected by orbiting satellites. Low thermal inertia means that the material does not hold its heat very long after the sun goes down. Generally, rocks have high thermal inertia, while sand has a low thermal inertia. A thin layer of dust, maybe less than one millimeter thick, covers all surfaces. Besides being magnetic, some part contains a small amount of chemically bound water.[16] [17] One type of soil, called Paso Robles, from the Columbia Hills, may be an evaporate deposit since it contains large amounts of sulfur, phosphorus, calcium, and iron.[18] Results from Spirits’ instruments of rocks on the plains show they contain the minerals pyroxene, olivine, plagioclase, and magnetite. The amounts and types of minerals found lead to a classification of primitive basalts—also called picritic basalts. They are comparable to ancient terrestrial rocks called basaltic komatiites. Rocks of the plains also resemble the basaltic shergottites, meteorites which came from Mars. [19] Plain’s rocks have been very slightly altered, probably by thin films of water that made them softer. Water also created veins of light colored material that may be bromine compounds, as well as coatings or rinds.[20] [21] It is commonly thought that Mars was first covered with the dark rock basalt. Over billions of years, the original rocks were broken down. By studying what minerals the beginning rocks turned into, we can tell how much water was involved and also the pH of the water. Coatings on the rocks may have taken place because they were buried and interacted with thin films of water and dust. One sign that they were altered was that it was easier to grind these rocks compared to the same types of rocks found on Earth. The first rock that Spirit studied was Adirondack. It turned out to be typical of the other rocks on the plains.

A variety of rocks were found and examined in the Columbia Hills.[22] All of the rocks in Columbia Hills show various degrees of alteration due to aqueous fluids.[23] They are enriched in the elements phosphorus, sulfur, chlorine, and bromine—all of which can be carried around in water solutions. The Columbia Hills’ rocks contain basaltic glass, along with varying amounts of olivine and sulfates.[24] [25] The olivine abundance varies indirectly with the sulfate abudance. This is exactly what is expected because water breaks down olivine but helps to produce sulfates.

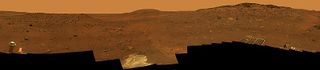

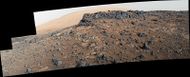

Wide view from Bonneville Crater Hills on right hills nicknamed the "Columbia Hills” where Spirit eventually drove to.

Clovis rock types are especially interesting because the Mössbauer spectrometer(MB) detected goethite in it.[26] Goethite forms only in the presence of water, so its discovery is the first direct evidence of past water in the Columbia Hills's rocks. In addition, the MB spectra of rocks and outcrops displayed a strong decline in olivine presence, [27] although the rocks probably once contained much olivine. Olivine breaks down in the presence of water; therefore, water must have been present to reduce the amount of Olivine.[28] Sulfate was found, and it needs water to be produced. The Independence class of rocks showed some signs of clay (perhaps montmorillonite a member of the smectite group). Anytime we find clay we know that water most have been around for a while. Towards the middle of the six-year mission (a mission that was supposed to last only 90 days), large amounts of pure silica were discovered in the soil. The silica could have come from the interaction of soil with acid vapors produced by volcanic activity in the presence of water or from water in a hot spring environment.[29]

A study of old data from the Miniature Thermal Emission Spectrometer, or Mini-TES and confirmed the presence of large amounts of carbonate-rich rocks, which means that regions of the planet may have once harbored water. As the Martian atmosphere contains mostly carbon dioxide, one would expect it to be changed into carbonates if water was available. Earth’s large limestone layers were made in this manner. The carbonates of Mars were discovered in an outcrop of rocks called "Comanche."[30] [31]

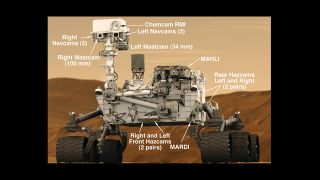

Discoveries from Curiosity

Just days into its mission, Curiosity discovered strong evidence of an ancient streambed where water once flowed knee-deep. As the mission progressed, more and more signs of water accumulated. Some of the signs of past water were the physical appearance of rocks. [32] [33] [34] [35] Many were rounded which means that they must have traveled in moving water to knocked off their original rough edges. .[36] [37] [38] Fine-grained rocks such as mudstone suggested deep water was present in the past. .[39] [40] [41] Clear proof of deltas was found. Deltas are formed when water carrying sediment enters a quiet body of water. As the water laden fluid hits the water it slows down and drops its sediment load, thereby causing a buildup of land. .[42] [43] [44] [45] Gale Crater contains a number of fans and deltas that provide information about lake levels in the past. These formations are: Pancake Delta, Western Delta, Farah Vallis delta and the Peace Vallis Fan.[46] In January, 2017, JPL scientists announced the discovery of mud cracks in Gale Crater. Such mud cracks form with the aid of water.[47] [48] [49] It was even determined that Gale Crater has liquid water at times according to measurements made by Curiosity. Since the humidity goes to 100% at night, salts, similar to calcium perchlorate, will absorb water from the air and make brine in the soil. Liquid water results even though the temperature is very low because salts lower the freezing point of water. We use this idea to melt snow/ice by spreading salt on roads. The liquid brine produced in the night at Gale Crater evaporates after sunrise. [50] [51] The amount of water was not enough to support life; however, it could allow salts to move around in the soil.[52] [53] Data from the rover’s Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) suggested subsurface water, amounting to as much as 4% water content, down to a depth of 2 feet (60cm), between the Bradbury Landing site to the Yellowknife Bay area in the Glenelg terrain.[54] On top of the physical evidence for water was data gathered by the sophisticated instruments on Curiosity. Many of the minerals identified were hydrated which required water. Some of these hydrated minerals are actinolite, montmorillonite, saponite, jarosite, halloysite, szomolnokite and magnesite. In some places 40 vol% of the minerals were hydrous minerals. [55]

Of great significance was the presence of clay which not only requires long periods of water, but the water had to be of neutral pH. A neutral pH is much more conducive to life. Great amounts of past water had been suggested by most scientists based upon decades of data from both orbiting satellites and lander/rovers. Mariner 9, Viking 1, Viking 2, Mars Odyssey, Mars Global Surveyor, Mars Express, and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter all have imaged features resembling river valleys.[56] [57] [58] [59] Many researchers believe there have been lakes on Mars. [60] [61] [62] Some have developed a argument for an ocean covering a full third of the planet.[63] [64] [65] [66] [67] [68] [69] [70] The Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity have found evidence for a watery past. However, the vast and varied amounts of data from Curiosity have sealed the case for a wet, early Mars. It is now accepted that a large, long-lived lake existed in Gale Crater. The presence of water is a prerequisite for life. Hence, the case for life on Mars at present or at least in the past has been greatly strengthened by Curiosity’s explorations, experiments, and measurements. More details about the many studies and observations that support a lake in Gale Crater can be found in the Marspedia article on Curiosity and the Wikipedia article on Aeolis quadrangle [[1]].

Ma'adim Vallis

A large, ancient river valley, called Ma'adim Vallis, enters at the south rim of Gusev Crater, so Gusev Crater was believed to be an ancient lake bed. However, it seems that a volcanic flow covered up the lakebed sediments. Apollinaris Patera, a large volcano, lies directly north of Gusev Crater.[71]> Recent studies lead scientists to believe that the water that formed Ma'adim Vallis originated in a complex of lakes.[72] [73] [74] The largest lake is located at the source of the Ma'adim Vallis outflow channel and extends into Eridania quadrangle and the Phaethontis quadrangle.[75] When this lake spilled over the low point in its boundary, a torrential flood would have moved north, carving the sinuous Ma'adim Vallis. At the north end of Ma'adim Vallis, the flood waters would have run into Gusev Crater.[76]

There is enormous evidence that water once flowed in river valleys on Mars. Images of curved channels have been seen in images from Mars spacecraft dating back to the early seventies with the Mariner 9 orbiter.

[77] [78] [79] [80]

Vallis (plural valles) is the Latin word for "valley". It is used in planetary geology for the naming of landform s what look like old river valleys . The Viking Orbiters caused a revolution in our ideas about water on Mars; huge river valleys were found in many areas. Space craft cameras showed that floods of water broke through dams, carved deep valleys, eroded grooves into bedrock, and traveled thousands of kilometers.[81] [82] Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag These layers are a complex record of the past. The rock layers probably took millions of years to be laid down within the crater, then more time to be eroded to make them visible.[83] The 5 km high mound is probably the thickest single succession of sedimentary rocks on Mars.[84] The lower formation may date from near the Noachian age, while the upper layer, separated by an erosional unconformity, may be as young as the Amazonian period.[85] The lower formation may have formed the same time as parts of Sinus Meridiani and Mawrth Vallis. The mound that lies in the center of Gale Crater was created by winds. Because the winds eroded the mound on one side more than another, the mound is skewed to one side, rather than being symmetrical.[86] [87] The upper layer may be similar to layers in Arabia Terra. Sulfates and Iron oxides have been detected in the lower formation and anhydrous phases in the upper layer.[88] There is evidence that the first phase of erosion was followed by more cratering and more rock formation.[89] Also of interest in Gale Crater is Peace Vallis, officially named by the IAU on September 26, 2012,[90] which 'flows' down out of the Gale Crater hills to the Aeolis Palus below, and which seems to have been carved by flowing water]].[91] [92]

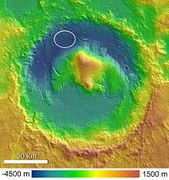

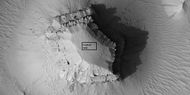

Gale Crater with Aeolis Mons rising from the center. The noted Curiosity rover landing area is near Peace Vallis in Aeolis Palus. > Curiosity landed in the northern part of the crater.

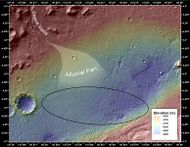

Peace Vallis and alluvial fan near the Curiosity rover landing ellipse and site (noted by +).

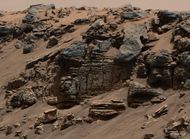

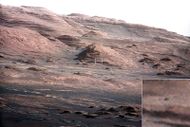

Aeolis Mons as viewed from the Curiosity rover (August 9, 2012) (white balanced image).

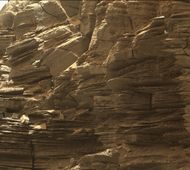

Layers at the base of Aeolis Mons - dark rock in inset is same size as the Curiosity rover (white balanced image).

Yardangs

Yardangs are common on Mars.[93] They are generally visible as a series of parallel linear ridges. Their parallel nature is thought to be caused by the direction of the prevailing wind.[94] Yardangs are common in the Medusae Fossae Formation on Mars.

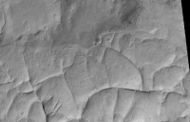

Inverted Relief

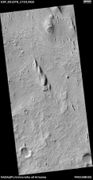

Some places on Mars show inverted relief. In these locations, a stream bed may be a raised feature, instead of a valley. The inverted former stream channels may be caused by the deposition of large rocks or due to cementation. In either case erosion would erode the surrounding land but leave the old channel as a raised ridge because the ridge will be more resistant to erosion. An image below, taken with HiRISE shows sinuous ridges that may be old channels that have become inverted. [94]

Fretted terrain

Parts of the Aeolis quadrangle contain fretted terrain which is characterized by cliffs, mesas, buttes, and straight-walled canyons. It contains scarps or cliffs that are 1 to 2 km in height.[95] [96]

Layered terrain

Researchers, writing in Icarus, have described layered units in the Aeolis quadrangle at Aeolis Dorsa. A deposit that contains yardang was formed after several other deposits. The yardangs contain a layered deposit called "rhythmite" which was thought to be formed with regular changes in the climate. Because the layers appear harden, a damp or wet environment probably existed at the time. The authors correlate these layered deposits to the upper layers of Gale crater’s mound (Mt. Sharp).[97] Many places on Mars show rocks arranged in layers. Sometimes the layers are of different colors. Light-toned rocks on Mars have been associated with hydrated minerals like sulfates. The Mars Rover Opportunity examined such layers close-up with several instruments. Some layers are probably made up of fine particles because they seem to break up into find dust. Other layers break up into large boulders so they are probably much harder. Basalt, a volcanic rock, is thought to in the layers that form boulders. Basalt has been identified on Mars in many places. Instruments on orbiting spacecraft have detected clay (also called phyllosilicate) in some layers. Recent research with an orbiting near-infrared spectrometer, which reveals the types of minerals present based on the wavelengths of light they absorb, found evidence of layers of both clay and sulfates in Columbus crater.[98] This is exactly what would appear if a large lake had slowly evaporated.[99] Moreover, because some layers contained gypsum, a sulfate which forms in relatively fresh water, life could have formed in the crater.[100] Scientists were excited about finding hydrated minerals such as sulfates and clays on Mars because they are usually formed in the presence of water.[101] Places that contain clays and/or other hydrated minerals would be good places to look for evidence of life.[102] Rock can form layers in a variety of ways. Volcanoes, wind, or water can produce layers.[103] Layers can be hardened by the action of groundwater. Martian ground water probably moved hundreds of kilometers, and in the process it dissolved many minerals from the rock it passed through. When ground water surfaces in low areas containing sediments, water evaporates in the thin atmosphere and leaves behind minerals as deposits and/or cementing agents. Consequently, layers of dust could not later easily erode away since they were cemented together. On Earth, mineral-rich waters often evaporate forming large deposits of various types of salts and other minerals. Sometimes water flows through Earth's aquifers, and then evaporates at the surface just as is hypothesed for Mars. One location this occurs on Earth is the Great Artesian Basin of Australia.[104] On Earth the hardness of many sedimentary rocks, like sandstone, is largely due to the cement that was put in place as water passed through. Silica cement is very hard, while calcite is not as hard.

Layered mesas, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Dark slope streaks are also visible.

Linear ridge networks

Linear ridge networks are found in various places on Mars in and around craters.[105] Ridges often appear as mostly straight segments. They are hundreds of meters long, tens of meters high, and several meters wide. It is thought that impacts created fractures in the surface, these fractures later acted as channels for fluids. Fluids cemented the structures. With the passage of time, surrounding material was eroded away, thereby leaving hard ridges behind. Since the ridges occur in locations with clay, these formations could serve as a marker for clay which requires water for its formation.[106][107][108]

Other features in Aeolis quadrangle

See also

Template:Div col Template:Div col end

References

- ↑ Davies, M.E.; Batson, R.M.; Wu, S.S.C. "Geodesy and Cartography" in Kieffer, H.H.; Jakosky, B.M.; Snyder, C.W.; Matthews, M.S., Eds. Mars. University of Arizona Press: Tucson, 1992.

- ↑ Blunck, J. 1982. Mars and its Satellites. Exposition Press. Smithtown, N.Y.

- ↑ Curiosity landed in the northern part of the crater; in some pictures it is hard to see where it landed. |author=NASA Staff |title=NASA Lands Car-Size Rover Beside Martian Mountain |url=http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.cfm?release=2012-230 |date=6 August 2012 |publisher=NASA/JPL

- ↑ http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/6785665%7Ctitle=Spirit rover follows up on scientific surprises|date=4 January 2005|

- ↑ U.S. department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey, Topographic Map of the Eastern Region of Mars M 15M 0/270 2AT, 1991

- ↑ http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/msl/multimedia/pia15292-Fig2.html%7Cdate=27 March 2012 |NASA

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Ori, G., I. Di Pietro, F. Salese. 2015. A WATERLOGGED MARTIAN ENVIRONMENT: CHANNEL PATTERNS AND SEDIMENTARY ENVIRONMENTS OF THE ZEPHYRIA ALLUVIAL PLAIN. 46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2015) 2527.pdf

- ↑ Christensen P (August 2004). "Initial Results from the Mini-TES Experiment in Gusev Crater from the Spirit Rover". Science. 305 (5685): 837–842.

- ↑ McSween, etal. 2004. "Basaltic Rocks Analyzed by the Spirit Rover in Gusev Crater". Science : 305. 842–845

- ↑ Arvidson R. E.; et al. (2004). "Localization and Physical Properties Experiments Conducted by Spirit at Gusev Crater". Science. 305 (5685): 821–824.

- ↑ Gelbert R.; et al. (2006). "The Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS): results from Gusev crater and calibration report". J. Geophys. Res. Planets. 111.

- ↑ Bertelsen, P., et al. 2004. "Magnetic Properties on the Mars Exploration Rover Spirit at Gusev Crater". Science: 305. 827–829

- ↑ Bell, J (ed.) The Martian Surface. 2008. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Gelbert, R. et al. "Chemistry of Rocks and Soils in Gusev Crater from the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer". Science: 305. 829-305

- ↑ Ming,D., et al. 2006 Geochemical and mineralogical indicators for aqueous processes in the Columbia Hills of Gusev crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res.111

- ↑ McSween, etal. 2004. "Basaltic Rocks Analyzed by the Spirit Rover in Gusev Crater". Science : 305. 842–845

- ↑ Arvidson R. E.; et al. (2004). "Localization and Physical Properties Experiments Conducted by Spirit at Gusev Crater". Science. 305 (5685): 821–824.

- ↑ McSween, etal. 2004. "Basaltic Rocks Analyzed by the Spirit Rover in Gusev Crater". Science : 305. 842–845

- ↑ Squyres, S., et al. 2006 Rocks of the Columbia Hills. J. Geophys. Res. Planets. 111

- ↑ Ming,D., et al. 2006 Geochemical and mineralogical indicators for aqueous processes in the Columbia Hills of Gusev crater, Mars. J. Geophys: Res.111

- ↑ Schroder, C., et al. 2005. European Geosciences Union, General Assembly, Geophysical Research abstr., Vol. 7, 10254, 2005

- ↑ Christensen, P. 2005. Mineral Composition and Abundance of the Rocks and Soils at Gusev and Meridiani from the Mars Exploration Rover Mini-TES Instruments AGU Joint Assembly, 23–27 May 2005 http://www.agu.org/meetings/sm05/waissm05.html

- ↑ Klingelhofer, G., et al. 2005. Lunar Planet. Sci. XXXVI abstr. 2349

- ↑ Schroder, C., et al. (2005) European Geosciences Union, General Assembly, Geophysical Research abstr., Vol. 7, 10254, 2005

- ↑ Morris,S., et al. Mossbauer mineralogy of rock, soil, and dust at Gusev crater, Mars: Spirit’s journal through weakly altered olivine basalt on the plains and pervasively altered basalt in the Columbia Hills. J. Geophys. Res.: 111

- ↑ https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/mer/mer-20070521.html

- ↑ https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/06/100603140959.htm

- ↑ Morris, Richard V.; Ruff, Steven W.; Gellert, Ralf; Ming, Douglas W.; Arvidson, Raymond E.; Clark, Benton C.; Golden, D. C.; Siebach, Kirsten; Klingelhöfer, Göstar; Schröder, Christian; Fleischer, Iris; Yen, Albert S.; Squyres, Steven W. (2010). "Identification of Carbonate-Rich Outcrops on Mars by the Spirit Rover". Science. 329 (5990): 421–4.

- ↑ https://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2012/sep/HQ_12-338_Mars_Water_Stream.html

- ↑ Chang, Alicia (September 27, 2012). "Mars rover Curiosity finds signs of ancient stream". Associated Press. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ↑ Williams, R. M. E.; Grotzinger, J. P.; Dietrich, W. E.; Gupta, S.; Sumner, D. Y.; Wiens, R. C.; Mangold, N.; Malin, M. C.; Edgett, K. S.; Maurice, S.; Forni, O.; Gasnault, O.; Ollila, A.; Newsom, H. E.; Dromart, G.; Palucis, M. C.; Yingst, R. A.; Anderson, R. B.; Herkenhoff, K. E.; Le Mouelic, S.; Goetz, W.; Madsen, M. B.; Koefoed, A.; Jensen, J. K.; Bridges, J. C.; Schwenzer, S. P.; Lewis, K. W.; Stack, K. M.; Rubin, D.; et al. (2013-07-25). "Martian fluvial conglomerates at Gale Crater". Science. 340 (6136): 1068–1072.

- ↑ Williams R.; et al. (2013). "Martian fluvial conglomerates at Gale Crater". Science. 340 (6136): 1068–1072.

- ↑ https://phys.org/news/2018-11-evidence-outburst-plentiful-early-mars.html

- ↑ Significance of Flood Deposits in Gale Crater, Mars. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. Vol. 50, No. 6 DOI: 10.1130/abs/2018AM-319960, https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2018AM/webprogram/Paper319960.html

- ↑ https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/11/181105132920.htm

- ↑ http://astrobiology.com/2015/10/wet-paleoclimate-of-mars-revealed-by-ancient-lakes-at-gale-crater.html

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=4734

- ↑ Grotzinger, J.P.; et al. (October 9, 2015). "Deposition, exhumation, and paleoclimate of an ancient lake deposit, Gale crater, Mars". Science: 350 (6257): aac7575.

- ↑ https://www.nasa.gov/press/2014/december/nasa-s-curiosity-rover-finds-clues-to-how-water-helped-shape-martian-landscape

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/09/science/-stronger-signs-of-life-on-mars.html

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/video/details.php?id=1346

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=4398

- ↑ Dietrich, W., M. Palucis, T. Parker, D. Rubin, K.Lewis, D. Sumner, R. Williams. 2014. Clues to the relative timing of lakes in Gale Crater. Eighth International Conference on Mars (2014) 1178.pdf.

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/spaceimages/details.php?id=pia21263

- ↑ http://spaceref.com/mars/desiccation-cracks-reveal-the-shape-of-water-on-mars.html

- ↑ Stein, N.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Schieber, J.; Mangold, N.; Hallet, B.; Newsom, H.; Stack, K.M.; Berger, J.A.; Thompson, L.; Siebach, K.L.; Cousin, A.; Le Mouélic, S.; Minitti, M.; Sumner, D.Y.; Fedo, C.; House, C.H.; Gupta, S.; Vasavada, A.R.; Gellert, R.; Wiens, R. C.; Frydenvang, J.; Forni, O.; Meslin, P. Y.; Payré, V.; Dehouck, E. (2018). "Desiccation cracks provide evidence of lake drying on Mars, Sutton Island member, Murray formation, Gale Crater". Geology. 46 (6): 515–518.

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=4549

- ↑ University of Copenhagen – Niels Bohr Institute. "Mars might have salty liquid water." ScienceDaily. 13 April 2015. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/04/150413130611.htm>.

- ↑ https://www.space.com/29072-mars-liquid-water-at-night.html

- ↑ Martin-Torre, F. et al. 2015. Transient liquid water and water activity at Gale crater on Mars. Nature geoscienceDOI:10.1038/NGEO2412

- ↑ https://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/msl/news/whatsnew/index.cfm?FuseAction=ShowNews&NewsID=1446

- ↑ Lin H.; et al. (2016). "Abundance retrieval of hydrous minerals around the Mars Science Laboratory landing site in Gale crater, Mars". Planetary and Space Science. 121: 76–82.

- ↑ https://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/PSP_007925_1990

- ↑ Goudge, T., et al. 2017. STRATIGRAPHY AND EVOLUTION OF DELTA CHANNEL DEPOSITS, JEZERO CRATER, MARS. Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017). 1195.pdf.

- ↑ Baker, V. 1982. The Channels of Mars. Univ. of Tex. Press, Austin, TX

- ↑ Baker, V., R. Strom, R., V. Gulick, J. Kargel, G. Komatsu, V. Kale. 1991. Ancient oceans, ice sheets and the hydrological cycle on Mars. Nature 352, 589–594.

- ↑ Goudge, T., K. Aureli, J. Head, C. Fassett, J. Mustard. 2015. Classification and analysis of candidate impact crater-hosted closed-basin lakes on Mars. Icarus: 260, 346-367.

- ↑ Fassett, C. J. Head. 2008. Valley network-fed, open-basin lakes on Mars: Distribution and implications for Noachian surface and subsurface hydrology. Icarus: 198, 37-56.

- ↑ Zhao, J., et al. 2018. PALEOLAKES IN THE NORTHWEST HELLAS REGION: IMPLICATIONS FOR PALEO-CLIMATE AND REGIONAL GEOLOGIC HISTORY. 49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2083).

- ↑ https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/06/100613181245.htm

- ↑ Gaetano Di Achille, Brian M. Hynek. Ancient ocean on Mars supported by global distribution of deltas and valleys. Nature, 2010; DOI: 10.1038/ngeo891

- ↑ Head et al. 1999. Possible Ancient oceans on Mars: Evidence from mars orbiter laser Altimeter Data. Science 286, 2134.

- ↑ Carr,M. 1996. Water on Mars. Oxford.

- ↑ Parker, T.J., Saunders, R.S., and Schneeberger, D.M., 1989, Transitional morphology in the west Deuteronilus Mensae region of Mars: Implications for modification of the lowland/upland boundary: Icarus , v. 82, 111–145, doi:10.1016/0019-1035(89)90027-4.

- ↑ Parker, T., et al. 1993. Coastal geomorphology of the Martian northern plains. Journal of Geophysical Research. 98. 11061.

- ↑ Carr, M. , J. Head. 2003. Oceans of Mars: An assessment of the observational evidence and possible fate. Journal of Geophysical Research. 108(E5). 5041. Doi:10.1029/2002JE001963, 2003.

- ↑ Carr, M. , J. Head. 2003. Oceans of Mars: An assessment of the observational evidence and possible fate. Journal of Geophysical Research. 108(E5). 5041. Doi:10.1029/2002JE001963, 2003.

- ↑ U.S. department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey, Topographic Map of the Eastern Region of Mars M 15M 0/270 2AT, 199

- ↑ Cabrol, N. and E. Grin (eds.). 2010. Lakes on Mars. Elsevier. NY.

- ↑ Rossman | first1 = R. | year = 2002 | title = A large paleolake basin at the head of Ma'adim Vallis, Mars | journal = Science | volume = 296 | issue = 5576 | pages = 2209–2212

- ↑ http://www.uahirise.org/ESP_037142_1430 |title=HiRISE | Chaos in Eridania Basin (ESP_037142_1430) |website=Uahirise.org |

- ↑ Science (journal)|Science]]|date=21 June 2002| volume=296| issue= 5576| pages= 2209–2212| doi=10.1126/science.1071143| title=A Large Paleolake Basin at the Head of Ma'adim Vallis, Mars| last=Rossman | first=P. Irwin III|author2=Ted A. Maxwell |author3=Alan D. Howard |author4=Robert A. Craddock |author5=David W. Leverington | url=http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/296/5576/2209%7C

- ↑ http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/ap020627.html%7Ctitle=APOD: 2002 June 27 – Carving Ma'adim Vallis|website=antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov|

- ↑ Baker, V. 1982. The Channels of Mars. Univ. of Tex. Press, Austin, TX

- ↑ last1 = Baker | first1 = V. | last2 = Strom | first2 = R. | last3 = Gulick | first3 = V. | last4 = Kargel | first4 = J. | last5 = Komatsu | first5 = G. | last6 = Kale | first6 = V. | date = 1991 | title = Ancient oceans, ice sheets and the hydrological cycle on Mars | journal = Nature | volume = 352 | issue = 6336 | pages = 589–594

- ↑ last1 = Carr | first1 = M | date = 1979 | title = Formation of Martian flood features by release of water from confined aquifers | journal = J. Geophys. Res. | volume = 84 | pages = 2995–300 |

- ↑ last1 = Komar | first1 = P | date = 1979 | title = Comparisons of the hydraulics of water flows in Martian outflow channels with flows of similar scale on Earth | journal = Icarus | volume = 37 | issue = 1 | pages = 156–181

- ↑ "Kieffer1992">author=Hugh H. Kieffer|title=Mars|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NoDvAAAAMAAJ%7C%7Cpublisher=University of Arizona Press|isbn=978-0-8165-1257-7

- ↑ Raeburn, P. 1998. Uncovering the Secrets of the Red Planet Mars. National Geographic Society. Washington D.C.

- ↑ http://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/mgs/msss/camera/images/dec00_seds/slides/265L/%7Ctitle=Mars Global Surveyor MOC2-265-L Release|website=mars.jpl.nasa.gov

- ↑ Milliken R. et al. | year = 2010 | title = Paleoclimate of Mars as captured by the stratigraphic record in Gale Crater | url = | journal = Geophysical Research Letters | volume = 37 | issue = 4| page = L04201

- ↑ Thompson | first1 = B. | date = 2011 | title = Constraints on the origin and evolution of the layered mound in Gale Crater, Mars using Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter data | journal = Icarus | volume = 214 | issue = 2 | pages = 413–432

- ↑ doi=10.1103/PhysRevE.96.043110| pmid=29347578|title = Turbulent flow over craters on Mars: Vorticity dynamics reveal aeolian excavation mechanism| journal=Physical Review E| volume=96| issue=4| pages=043110|year = 2017|last1 = Anderson|first1 = William| last2=Day| first2=Mackenzie

- ↑ Anderson | first1 = W. | last2 = Day | first2 = M. | year = 2017 | title = Turbulent flow over craters on Mars: Vorticity dynamics reveal aeolian excavation mechanism | url = | journal = Phys. Rev. E | volume = 96 | issue = 4| page = 043110 | doi=10.1103/physreve.96.043110| pmid = 29347578

- ↑ Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken. 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM.

- ↑ http://www.msss.com/mars_images/moc/dec00_seds/slides/265E%7Ctitle=Mars Global Surveyor MOC2-265-E Release|website=www.msss.com|accessdate=16 June 2017

- ↑ IAU Staff |title=Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature: Peace Vallis |url=http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Feature/15036?__fsk=-365499458 |date=September 26, 2012|publisher=IAU|

- ↑ Brown|first1=Dwayne |last2=Cole |first2=Steve |last3=Webster |first3=Guy |last4=Agle |first4=D.C.|title=NASA Rover Finds Old Streambed http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2012/sep/HQ_12-338_Mars_Water_Stream.html |date=September 27, 2012|publisher=NASA

- ↑ NASA |title=NASA's Curiosity Rover Finds Old Streambed on Mars – video (51:40)|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fYo31XjoXOk |date=September 27, 2012 |publisher=NASA Television|

- ↑ Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken (eds.) 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Sharp, R. 1973. Mars Fretted and chaotic terrains. J. Geophys. Res.: 78. 4073–4083

- ↑ Kieffer, Hugh H.; et al., eds. (1992). Mars. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. Template:ISBN.

- ↑ title=Stratigraphy of Aeolis Dorsa, Mars: Stratigraphic context of the great river deposits |journal=Icarus |volume=253 |pages=223–42 |year=2015 |last1=Kite |first1=Edwin S. |last2=Howard |first2=Alan D. |last3=Lucas |first3=Antoine S. |last4=Armstrong |first4=John C. |last5=Aharonson |first5=Oded |last6=Lamb |first6=Michael P. |

- ↑ Cabrol, N. and E. Grin (eds.). 2010. Lakes on Mars. Elsevier.NY.

- ↑ Wray, J. et al. 2009. Columbus Crater and other possible plaeolakes in Terra Sirenum, Mars. Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. 40: 1896.

- ↑ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2009/11/091125-mars-crater-lake-michigan-water_2.html |title=Martian "Lake Michigan" Filled Crater, Minerals Hint |publisher=News.nationalgeographic.com |

- ↑ http://themis.asu.edu/features/nilosyrtis |title=Target Zone: Nilosyrtis? | Mars Odyssey Mission THEMIS |publisher=Themis.asu.edu |

- ↑ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/PSP_004046_2080 |title=HiRISE | Craters and Valleys in the Elysium Fossae (PSP_004046_2080) |publisher=Hirise.lpl.arizona.edu

- ↑ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu?PSP_008437_1750 |title=HiRISE | High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment |publisher=Hirise.lpl.arizona.edu?psp_008437_1750 |

- ↑ Habermehl, M. A. (1980) The Great Artesian Basin, Australia. J. Austr. Geol. Geophys. 5, 9–38.

- ↑ Head, J., J. Mustard. 2006. Breccia dikes and crater-related faults in impact craters on Mars: Erosion and exposure on the floor of a crater 75 km in diameter at the dichotomy boundary, Meteorit. Planet Science: 41, 1675-1690.

- ↑ "Mineralogy of the Nili Fossae region with OMEGA/Mars Express data: 2. Aqueous alteration of the crust" (2007). J. Geophys. Res. 112 (E8): E08S04. doi:. Bibcode: 2007JGRE..112.8S04M.

- ↑ Mustard et al., 2007. Mineralogy of the Nili Fossae region with OMEGA/Mars Express data: 1. Ancient impact melt in the Isidis Basin and implications for the transition from the Noachian to Hesperian, J. Geophys. Res., 112.

- ↑ "Composition, Morphology, and Stratigraphy of Noachian Crust around the Isidis Basin" (2009). J. Geophys. Res. 114 (7): E00D12. doi:. Bibcode: 2009JGRE..114.0D12M.

Further reading

- Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken (eds.). 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM.

- Lakdawalla E | year = 2011 | title = Target: Gale Curiosity Will Soon Have a New Home | url = | journal = The Planetary Report | volume = 31 | issue = 4| pages = 15–21

- Lakdawalla, E. 2018. The Design and Engineering of Curiosity: How the Mars Rover Performs its job. Springer Praxis Publishing. Chichester, UK

External links

- Video (04:32) – Evidence: Water "Vigorously" Flowed On Mars – September, 2012

- Lakes, Fans, Deltas and Streams: Geomorphic Constraints ...

- Lakes on Mars – Nathalie Cabrol (SETI Talks)

- Boron Discovered in Ancient Habitable Mars Groundwater

- Steven Benner – Life originated on Mars? – 19th Annual International Mars Society Convention

- John Grotzinger - Project Scientist, Curiosity - 20th Annual International Mars Society Convention