Medusae Fossae

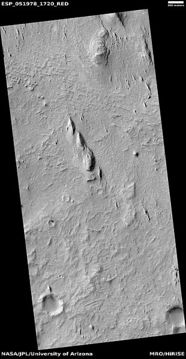

The Medusae Fossae Formation is a large geological formation of probable volcanic origin on the planet Mars.[1]

It is named for the Medusa of Greek mythology. "Fossae" is Latin for "trenches". The formation is a collection of soft, easily eroded deposits that extends off and on for more than 5,000 km along the equator.

Its roughly-shaped regions extend from just south of Olympus Mons to Apollinaris Patera, with a smaller additional region closer to Gale Crater.[2]

It has been determined that the Medusae Fossae Formation as the single largest source of dust on Mars.[3]

The total area of the Medusae Fossae Formation is equal to 20% the size of the continental United States.[4]

The formation straddles what is called the martian dichotomy|highland - lowland boundary near the Tharsis and Elysium volcanic areas, and extends across five quadrangles: Amazonis, Tharsis, Memnonia, Elysium, and Aeolis.

Origin and age

The origin of the formation is unknown, but many theories have been presented over the years.

The Medussae Fossae Formation is part of an area called "stealth terrain" that produces little to no radar return, making it appear "stealthy" to radar signals. It is believed to be covered by a thick mantle of fine-grained, unconsolidated material, likely volcanic ash or dust.[5]

In 2020, a group of researchers headed by Peter Mouginis-Mark has hypothesized that the formation could have been formed from pumice rafts from the volcano Olympus Mons.[6] In 2012, a group headed by Laura Kerber hypothesized that it could have been formed from ash from the volcanoes Apollinaris Mons, Arsia Mons, and possibly Pavonis Mons.[7]

Its density and high content of sulfur and chlorine, suggests an explosive volcanic origin. It may have been deposited in periodic eruptions over an interval of 500 million years.[8]

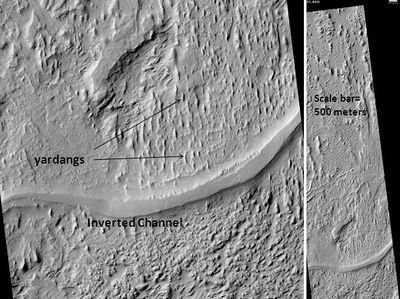

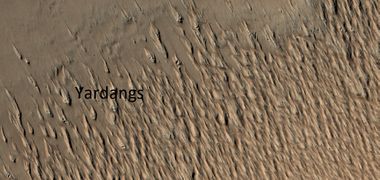

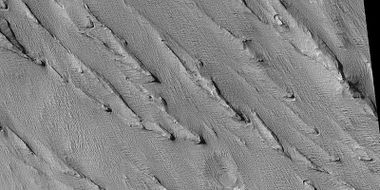

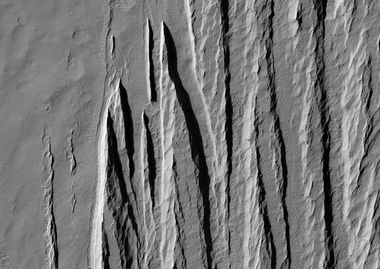

The surface of the formation has been eroded by the wind into a series of linear ridges called yardangs. The wind shapes things by bouncing sand particles.[9] Layers are seen in parts of the formation. [10] These ridges generally point in direction of the prevailing winds that carved them, and demonstrate the erosive power of Martian winds. The easily eroded nature of the Medusae Fossae Formation suggests that it is composed of weakly cemented particles, and was most likely formed by the deposition of wind-blown dust or volcanic ash. Layers are seen in parts of the formation.

Yardangs are common on Mars.[11] They are generally visible as a series of parallel linear ridges. Their parallel nature is thought to be caused by the direction of the prevailing wind.[12]

Evidence of water

Evidence of water in the Medusae Fossae Formation (MFF) has been found by researchers. It is a vast, ancient deposit of layered water ice buried beneath a thick layer of dry dust. The water may have been deposited during periods of higher axial tilt, when the Martian equator was colder. Scientists have identified this ice using radar, and if melted, it would contain enough water to cover the entire planet in 1.5 to 2.7 meters of water. The ice was discovered with the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionospheric Sounding (MARSIS) instrument detected subsurface layers of ice. These ice-rich deposits are estimated to be up to 3.7 kilometers thick in some areas. Calculations suggest a total volume of water nearly as great as our Red Sea.[13]

Scientists are excited about a possible “oasis” of bulk ice in the equatorial region. Having a source of ice near the equator could make it easier for future human exploration. Landings near the equator are more efficient at the equator. We know that Mars has much frozen ground, but at some distance from the equator. Explosive volcanic eruptions can propel large pulses of water vapor from the volcano to higher levels of the atmosphere. These eruptions could deposit an ash-ice mixture, or a layer of ice covered in ash. Under certain conditions the ice may be preserved for long periods.[14]

Instruments on Mars orbiters have detected excess hydrogen in the upper meter of the surface in equatorial regions (That’s between ±30°). The hydrogen is assumed to come from water molecules. Water contains the elements hydrogen and oxygen. These measurements came from the Mars Odyssey Neutron Spectrometer (MONS),[15] [16] [17] the Mars Odyssey High Energy Neutron Detector (HEND),[18] and the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter’s Fine Resolution Epithermal Neutron Detector (FREND).[19]

The Medusae Fossae Formation is surrounded by possible volcanic sources, including Olympus Mons and the Tharsis Montes to the east, the Elysium volcanoes and Cerberus Fissures to the north, and Apollinaris Mons, an isolated volcano situated in the center of the deposit. These eruptions may have caused meteorological events that influenced the surface of Mars. Terrestrial explosive volcanic eruptions are often likened to “dirty thunderstorms” due to their electrical activity, convective updrafts, and elevated water contents (from magmatic volatiles, interactions with water).[20] This water can encase volcanic ash, leading to phenomena like volcanic hail, graupel, snow, and rain.[21] Examples include the volcanic hail in the 2009 eruption of Redoubt Volcano in Alaska,[22] and volcanically induced thunderstorms and rain showers following the 1991 Mount Pinatubo, Philippines eruption.[23] Since most ash particles are effective ice-forming nuclei, volcanic clouds and subsequent precipitation could have played a key role in shaping Mars’ surface by delivering ash-ice mixtures or ice layers covered in ash. This ash can insulate and preserve underlying ice.[24]

The water detected by orbiting instruments could be found in many different materials. Some are (1) adsorbed water onto regolith particles.[25] [26], (2) water incorporated into the mineral’s crystal structure (i.e., hydrated minerals),[27],(3) OH and H2O located in the structure of salt hydrates, [28] (4) small amounts of water ice in the pores between regolith particles,[29], (5) hydrous alteration in an aqueous environment,[30] (6) sulfate hydration in the shallow subsurface,[31]. (7) OH that is part of the structure of clays and trapped water between clay layers[32] and/or (8) water interacting with cations located in the pores of zeolite mineral structure. [33] [34]

See also

- Amazonis quadrangle

- Geography of Mars

- High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE)

- HiWish program

- Layers on Mars

- Mars Global Surveyor

External links

References

- ↑ "The Medusa Fossae formation on Mars". European Space Agency. 29 March 2005.

- ↑ Lujendra Ojha; Kevin Lewis; Suniti Karunatillake; Mariek Schmidt July 20, 2018 The Medusae Fossae Formation as the single largest source of dust on Mars". Nature Communications. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ↑ |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-05291-5/figures/1%7Cjournal=Nature Communications|language=en|

- ↑ |pmid=30030425 |pmc=6054634 |title=The Medusae Fossae Formation as the single largest source of dust on Mars |journal=Nature Communications |volume=9 |issue=1 |pages=2867 |year=2018 |last1=Ojha |first1=Lujendra |last2=Lewis |first2=Kevin |last3=Karunatillake |first3=Suniti |last4=Schmidt |first4=Mariek |

- ↑ Geologic context of the Mars radar “Stealth” region in southwestern Tharsis Kenneth S. Edgett, Bryan J. Butler, James R. Zimbelman, Victoria E. Hamilton. 1997 JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 102, NO. E9, PAGES 21,545-21,567. https://doi.org/10.1029/97JE01685

- ↑ Scientists Float a New Theory on the Medusae Fossae Formation". Eos. 19 May 2020.

- ↑ "The dispersal of pyroclasts from ancient explosive volcanoes on Mars: Implications for the friable layered deposits" (2012). Icarus 219 (1): 358–381. doi:.

- ↑ "Sedimentary Geology of Mars" (2012). Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 123 (6): 169–182. doi:.

- ↑ Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken (eds.) 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM

- ↑ name="hiroc.lpl.arizona.edu"

- ↑ Thomas Watters et al, Evidence of Ice-Rich Layered Deposits in the Medusae Fossae Formation of Mars, Geophysical Research Letters (2024).

- ↑ Ayris, P. M. & Delmelle, P. The immediate environmental effects of tephra emission. Bull. Volcanol. 74, 1905–1936 (2012).

- ↑ Feldman, W. C. et al. Global distribution of near-surface hydrogen on Mars. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 109, E09006 (2004).

- ↑ Wilson, J. T. et al. Equatorial locations of water on Mars: improved resolution maps based on Mars Odyssey Neutron Spectrometer data. Icarus 299, 148–160 (2018).

- ↑ Evans, L. G., Reedy, R. C., Starr, R. D., Kerry, K. E. & Boynton, W. V. Analysis of gamma ray spectra measured by Mars Odyssey. J. Geophys. Res. 111, E03S04 (2006).

- ↑ Mitrofanov, I. G. et al. Soil water content on Mars as estimated from neutron measurements by the HEND instrument onboard the 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft. Sol. Syst. Res. 38, 253–257 (2004).

- ↑ Rossbacher, L. A. & Judson, S. Ground ice on Mars: inventory, distribution, and resulting landforms. Icarus 45, 39–59 (1981).

- ↑ Brown, R. J., Bonadonna, C. & Durant, A. J. A review of volcanic ash aggregation. Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C. 45, 65–78 (2012).

- ↑ Van Eaton, A. R. et al. Hail formation triggers rapid ash aggregation in volcanic plumes. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–7 (2015).

- ↑ Van Eaton, A. R. et al. Hail formation triggers rapid ash aggregation in volcanic plumes. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–7 (2015).

- ↑ .Oswalt, J. S., Nichols, W. & O’Hara, J. F. Meteorological observations of the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption. In Fire and Mud: Eruptions of Pinatubo, Philippines (eds Newhall, C. G. & Punongbayan, S.) 545–570 (University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1996).

- ↑ Durant, A. J., Shaw, R. A., Rose, W. I., Mi, Y. & Ernst, G. G. J. Ice nucleation and overseeding of ice in volcanic clouds. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 113, 1–13 (2008).

- ↑ Feldman, W. C. et al. Global distribution of near-surface hydrogen on Mars. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 109, E09006 (2004)

- ↑ Malakhov, A. V. et al. Ice permafrost ‘“oases”’ close to Martian equator: planet neutron mapping based on data of FREND instrument onboard TGO orbiter of Russian-European ExoMars mission. Astron. Lett. 46, 407–421 (2020)

- ↑ Malakhov, A. V. et al. Ice permafrost ‘“oases”’ close to Martian equator: planet neutron mapping based on data of FREND instrument onboard TGO orbiter of Russian-European ExoMars mission. Astron. Lett. 46, 407–421 (2020)

- ↑ Basilevsky, A. T. et al. Search for traces of chemically bound water in the martian surface layer based on HEND measurements onboard the 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft. Sol. Syst. Res. 37, 387–396 (2003).

- ↑ Malakhov, A. V. et al. Ice permafrost ‘“oases”’ close to Martian equator: planet neutron mapping based on data of FREND instrument onboard TGO orbiter of Russian-European ExoMars mission. Astron. Lett. 46, 407–421 (2020)

- ↑ Hood, D. R. et al. Contrasting regional soil alteration across the topographic dichotomy of Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 13,668–13,677 (2019).

- ↑ Karunatillake, S. et al. Sulfates hydrating bulk soil in the Martian low and middle latitudes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 7987–7996 (2014)

- ↑ Feldman, W. C. et al. Global distribution of near-surface hydrogen on Mars. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 109, E09006 (2004)

- ↑ Feldman, W. C. et al. Global distribution of near-surface hydrogen on Mars. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 109, E09006 (2 004).

- ↑ Hamid, S.S., Kerber, L. & Clarke, A.B. Precipitation induced by explosive volcanism on Mars and its implications for unexpected equatorial ice. Nat Commun 16, 8923 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63518-8