Curiosity

| This article is a stub. You can help Marspedia by expanding it. |

Curiosity is the last and most advanced rover from NASA. It carries several instruments for scientific investigation. One of the goals is to find signs of life on the Martian surface or a few centimeters below.

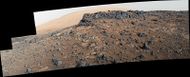

Curiosity took off on November 26, 2011 atop an Atlas V rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.[1] It landed on August 6, 2012 in Gale Crater in the Aeolis quadrangle at 4.5895 degrees S and 137.4417 degrees E.[2] [3] Curiosity nailed its landing—“so close to the target that the offset was almost equivalent to a rounding error.”[4] Its destination, Gale Crater, was chosen because it contained a large layered mountain. The mountain’s original name was Mt. Aeolis, but it has been changed to Mt. Sharp in honor of Robert P. Sharp (1911–2004), a field geologist and professor at Caltech. The original name Mt. Aeolis came from Greek mythology, it was a floating island where winds were held in a cave inside a mountain.[5] With a height of 18,000 feet (3.4 miles--5.5 Km), Mt. Sharp is higher than any mountain in the continental United States.[6] [7] “Bradbury,” after the famous science fiction writer Ray Bradbury was picked for the name of the touchdown spot.[8]

[File:PIA16158-Mars Curiosity Rover-Water-AlluvialFanlandingsite.jpg [|600pxr| Landing site for Curiosity in northern part of Gale Crater The black oval indicates the "landing ellipse," and the cross shows where the rover actually landed. Nearby a stream, called “Peace Vallis” built an alluvial fan from water and sediments.]] File:PIA16158-Mars Curiosity Rover-Water-AlluvialFanlandingsite.jpg|landing site for Curiosity in northern part of Gale Crater The black oval indicates the "landing ellipse," and the cross shows where the rover actually landed. Nearby a stream, called “Peace Vallis” built an alluvia fan from water and sediments.

Contents

Spacecraft

Curiosity has a mass of 1,982 pounds max (899 kilograms). It is 10 feet (3 meters) long, 9 feet (2.7 meters) wide, and 7 feet (2.2 meters) tall. Power is provided by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator that provides (about 2,700 watt hours per sol).[9] However, it does not generate much instant power. Instead it is slowing charging the batteries all the time. When the batteries have a good charge, they can supply Curiosity with all the power it requires. It uses two rechargeable lithium-ion batteries with each having a capacity of about 42 ampere-hours.[10]

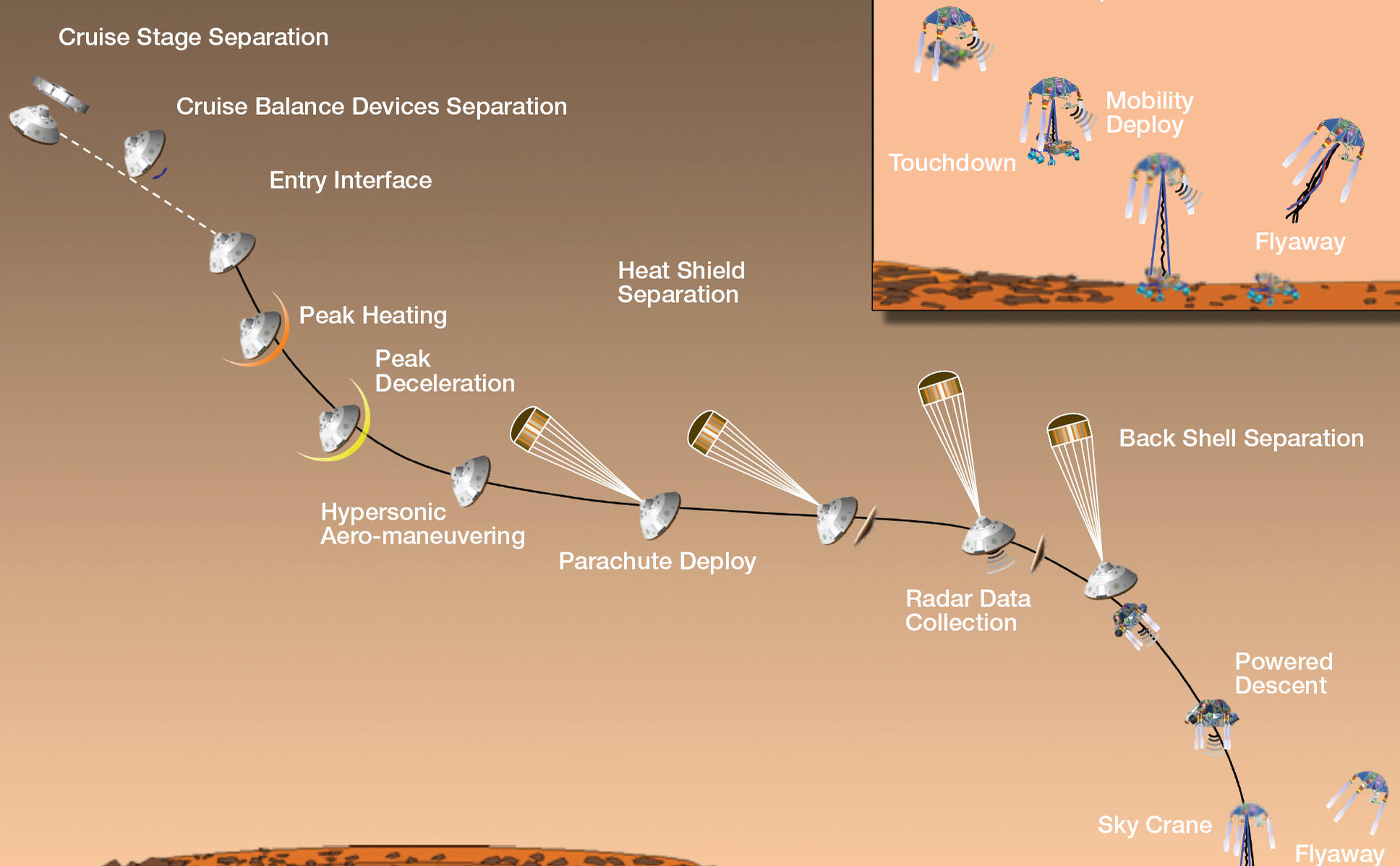

File:4392 edl20120809-full2landingsteps.jpg|Events for Curiosity’s landing It employed an interesting, though complex, method of landing. Because it had so many instruments and mass it could not use the bouncing air bags that other successful rovers had used. First parachutes slowed the craft, and then four engines fired to just about stop the descent. With the vehicle basically floating above the ground, it was lowered down a “umbilical cord.” Upon safely landing, the cord was cut and the descent stage flew away at full throttle. This new scheme of landing is called the Sky Crane maneuver. [11] Curiosity is a rover, but a very slow rover. Its top speed is 450 feet/hour—less than a quarter mile/hour. Many seem to believe that we should stick to an unmanned approach to exploration. However, remember the Apollo astronauts went 8-11 miles/hour on the far rougher terrain on the moon. .[12]

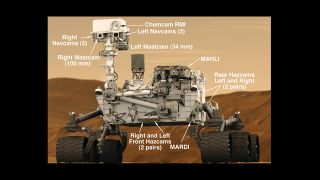

Instruments

File:4077 malin-4rovercam-full.jpg|Cameras on Curiosity Cameras: Mast Camera (Mastcam)

Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI)

Mars Descent Imager (MARDI)

Spectrometers: Alpha Particle X-Ray Spectrometer (APXS)

Chemistry & Camera (ChemCam)

Chemistry & Mineralogy X-Ray Diffraction/X-Ray Fluorescence Instrument (CheMin) Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) Instrument Suite

Radiation Detectors: Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD)

Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN)

Environmental Sensors: Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS)

Atmospheric Sensors

Mars Science Laboratory Entry Descent and Landing Instrument (MEDLI)[13]

Findings

Water

Just days into its mission, Curiosity discovered strong evidence of an ancient streambed where water once flowed knee-deep.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag [14] [15] [16] Many researchers believe there have been lakes on Mars. [17] [18]Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] The Phoenix Mars Mission actually found ice in the soil and there may have been drops of liquid water observed that formed with the heat of the descent engines.[26] [27] [28] [29] [30] The Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity have found evidence for a watery past. However, the vast and varied amounts of data from Curiosity have sealed the case for a wet, early Mars. It is now accepted that a large, long-lived lake existed in Gale Crater.

The presence of water is a prerequisite for life. Hence, the case for life on Mars at present or at least in the past has been greatly strengthened by Curiosity’s explorations, experiments, and measurements.

Following are some of the individual studies that have led to the conclusion that Gale Crater once harbored a lake.

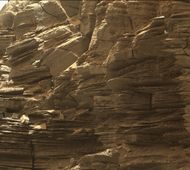

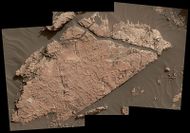

File:5316 pia17062 Hottah WB-full2conglomerate.jpg|Conglomerate rock called “Hottah" after Hottah Lake in Canada's Northwest Territories. Conglomerate is composed of rounded pebbles that had to be formed in running water. As early as September 27, 2012,NASA scientists announced that Curiosity (rover) found evidence for an ancient streambed suggesting a "vigorous flow" of water on Mars.[31] [32] [33] [34] Mars scientists, in a press conference on December 8, 2014, described observations by Curiosity rover that show Mars' Mount Sharp was made by sediments deposited in a large lake bed over tens of millions of years. This finding suggests the climate of ancient Mars could have been conducive to long-lasting lakes at many places on the Planet. Many scientists had suggested this long ago. There is a long list of where lakes may have existed in the distant past. Rock layers in Gale imply that a huge lake was filled and evaporated many times. Many deltas stacked upon each other support this contention.[35] [36] [37] [38]

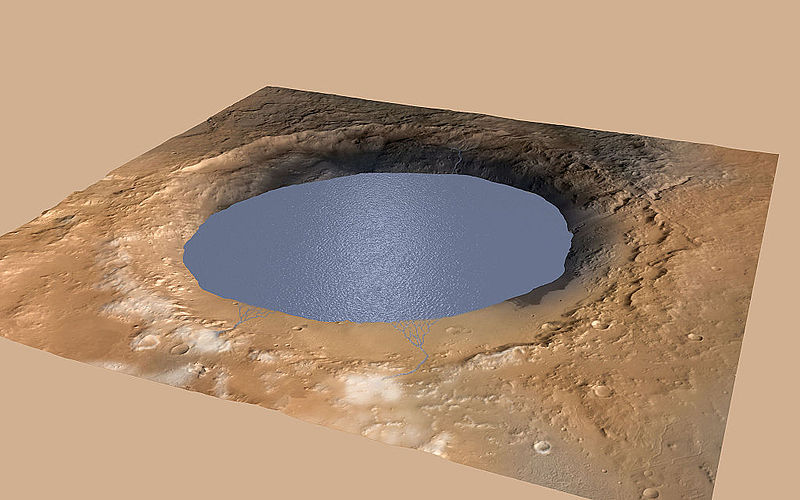

File:PIA19080-MarsRoverCuriosity-AncientGaleLake-Simulated-20141208.jpg|Simulated view of past lake in Gale Crater

After more observations, on October 8, 2015, a large team of scientists confirmed the existence of long-lasting lakes in Gale Crater. The team came to this conclusion based on evidence of old streams with coarser gravel in addition to places where streams appear to have emptied out into bodies of standing water. If lakes were once present, Curiosity would start seeing water-deposited, fine-grained rocks closer to Mount Sharp. That is exactly what was observed. Finely laminated mudstones were discovered by Curiosity; this lamination represents the settling of plumes of fine sediment through a standing body of water. Sediment deposited the Gale Crater lake formed the lower portion of Mount Sharp, the mountain in Gale crater.[39] [40] [41]

Research presented in 2018 at the Geological Society of America Annual Meeting in Indianapolis, Indiana explained evidence for huge floods in Gale Crater. Of great significance was a conglomerate rock unit with particles up to 20 centimeters across. To create such a type of rock water must have been 10 to 20 meters in depth. Between 2 million years to 12,000 years ago, Earth experienced these types of floods.[42] [43] [44] Conglomerate is a rock composed of rounded rocks of various sizes. Rounded rocks are produced by traveling down streams. In the streams they become rounded by hitting the steam bottom and each other.

Besides physical evidence of water, there was much more supporting signs of water that was detected by various instruments on Curiosity. Although some are subtle and complicated, they are consistent with a history of water. For instance, many minerals require water for their formation. Many of these types of minerals are in Gale Crater. Curiosity was able to even examine small veins and determine their composition which often turned out to be different than the surrounding rocks. Veins form when fluids move through cracks in rocks.[45]

File:PIA19080-MarsRoverCuriosity-AncientGaleLake-Simulated-20141208.jpg|Simulated view of past lake in Gale Crater

After more observations, on October 8, 2015, a large team of scientists confirmed the existence of long-lasting lakes in Gale Crater. The team came to this conclusion based on evidence of old streams with coarser gravel in addition to places where streams appear to have emptied out into bodies of standing water. If lakes were once present, Curiosity would start seeing water-deposited, fine-grained rocks closer to Mount Sharp. That is exactly what was observed. Finely laminated mudstones were discovered by Curiosity; this lamination represents the settling of plumes of fine sediment through a standing body of water. Sediment deposited the Gale Crater lake formed the lower portion of Mount Sharp, the mountain in Gale crater.[39] [40] [41]

Research presented in 2018 at the Geological Society of America Annual Meeting in Indianapolis, Indiana explained evidence for huge floods in Gale Crater. Of great significance was a conglomerate rock unit with particles up to 20 centimeters across. To create such a type of rock water must have been 10 to 20 meters in depth. Between 2 million years to 12,000 years ago, Earth experienced these types of floods.[42] [43] [44] Conglomerate is a rock composed of rounded rocks of various sizes. Rounded rocks are produced by traveling down streams. In the streams they become rounded by hitting the steam bottom and each other.

Besides physical evidence of water, there was much more supporting signs of water that was detected by various instruments on Curiosity. Although some are subtle and complicated, they are consistent with a history of water. For instance, many minerals require water for their formation. Many of these types of minerals are in Gale Crater. Curiosity was able to even examine small veins and determine their composition which often turned out to be different than the surrounding rocks. Veins form when fluids move through cracks in rocks.[45]

Some of the more indirect findings are mentioned below. Signs of mineral hydration, probably hydrated calcium sulfate, were reported by NASA on March 18, 2013, in several rock samples including the broken fragments of "Tintina" rock and "Sutton Inlier" rock plus in veins and nodules in other rocks like "Knorr" rock and "Wernicke" rock.[46] [47] Minerals that are hydrated needed water to become hydrated, so finding hydrated minerals means that water must have been present. By the start of 2016, Curiosity had detected seven hydrous minerals. The minerals are actinolite, montmorillonite, saponite, jarosite, halloysite, szomolnokite and magnesite. In some places 40 vol% of the minerals were hydrous minerals. Note that all of these minerals must have formed in water. [48]

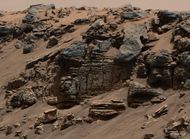

File:7505 mars-curiosity-rover-gale-crater-beauty-shot-pia19839-full2.jpg|Rocks layers from the “Kimberley” formation Layers like this are usually formed under water. Scientists found manganese oxides in mineral veins in the "Kimberley" region of Gale Crater by using Curiosity's laser-firing device (ChemCam). These minerals need lots of water and oxidizing conditions to form; therefore, this finding points to a water-rich, oxygen-rich past.[49] [50] [51] A study of types of minerals in veins found that evaporating lakes were extant in the past in Gale crater. The Sheepbed Member mudstones of Yellowknife Bay (YKB) were investigated in this research.[52] [53] In January, 2017, JPL scientists announced the discovery of mud cracks in Gale Crater. Such mud cracks form with the aid of water.[54] [55] [56] Analysis using data from the rover’s Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) scientists acquired evidence of subsurface water, amounting to as much as 4% water content, down to a depth of 2 feet (60cm), between the Bradbury Landing site to the Yellowknife Bay area in the Glenelg terrain.[57] Mars even has liquid water at times according to measurements made by Curiosity. Since the humidity goes to 100% at night, salts, similar to calcium perchlorate, will absorb water from the air and make brine in the soil. This manner in which a salt absorbs water from the air is called deliquescence. Liquid water results even though the temperature is very low because salts lower the freezing point of water. We use this idea to melt snow/ice by spreading salt on roads. The liquid brine produced in the night evaporates after sunrise. Higher amounts of liquid water are expected in higher latitudes where the colder temperature can result in higher levels of humidity more often.[58] [59] Researchers cautioned that the amount of water was not enough to support life’ however, it could allow salts to move around in the soil.[60] The brines would occur commonly in the upper 5 cm of the surface, but there is evidence that the effects of liquid water can be detected down to 15 cm. Chlorine-bearing brines are corrosive; therefore design changes may need to be made for future landers.[61]

Radiation levels

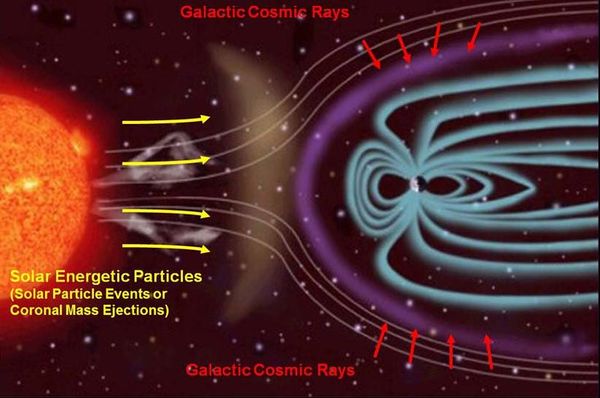

Measurements of radiation levels are necessary for human missions to the surface of Mars, to provide microbial survival times of any possible extant or past life, and to determine how long conceivable organic biosignatures can be preserved. Astronauts on Mars would need to spend most of their time underground for protection from radiation. Future colonies would probably be in lava tunnels; Mars has an abundance of volcanoes, so lava tunnels may be common. Also, perhaps in the future we may have developed robotic earth movers which could move dirt around for cover.

File:PIA16938-RadiationSources-InterplanetarySpace.jpg|Sources of dangerous radiation in space

Curiosity took accurate readings of radiation on the way to Mars as well as on the surface. The absorbed dose and dose equivalent from galactic cosmic rays and solar energetic particles on the Martian surface for ~300 days of observations during the current solar maximum was measured. This study estimates that a one-meter depth drill is necessary to access possible viable radioresistant microbe cells. The actual absorbed dose measured by the Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) is 76 mGy/yr at the surface. Based on these quantities, for a round trip Mars surface mission with 180 days (each way) cruise, and 500 days on the Martian surface for this current solar cycle, an astronaut would be exposed to a total mission dose equivalent of ~1.01 sievert. One Sievert exposure is associated with a five percent increase in risk for developing fatal cancer. NASA's current lifetime limit for increased risk for its astronauts operating in low-Earth orbit is three percent.Cite error: Closing

Curiosity took accurate readings of radiation on the way to Mars as well as on the surface. The absorbed dose and dose equivalent from galactic cosmic rays and solar energetic particles on the Martian surface for ~300 days of observations during the current solar maximum was measured. This study estimates that a one-meter depth drill is necessary to access possible viable radioresistant microbe cells. The actual absorbed dose measured by the Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) is 76 mGy/yr at the surface. Based on these quantities, for a round trip Mars surface mission with 180 days (each way) cruise, and 500 days on the Martian surface for this current solar cycle, an astronaut would be exposed to a total mission dose equivalent of ~1.01 sievert. One Sievert exposure is associated with a five percent increase in risk for developing fatal cancer. NASA's current lifetime limit for increased risk for its astronauts operating in low-Earth orbit is three percent.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

Measuring the radiation levels, Curiosity finds no stronger radiation on the Martian surface than in low Earth orbit, where the ISS is. This seems the result of Mars' atmosphere deflecting parts of the cosmic rays. This is very good news as it simplifies significantly the construction of living quarters for the settlers. However, the intensity of solar flares still needs to be measured.[62]

The origin of Cosmic rays are not greatly understood. Most are small atomic particles, but some are the nuclei of heavier atoms.[63]

They are a major concern in space because they can damage living cells and electronics. The Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field protect us from their effects. However, they are a potential problem on Mars which has only a very thin atmosphere and no magnetic field. A small number of cosmic rays can have about 40 million times the energy of particles accelerated by the largest particle accelerators.[64] The energy of the most powerful cosmic rays is equal to a baseball moving at 56 mph (90 km/hr.)Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

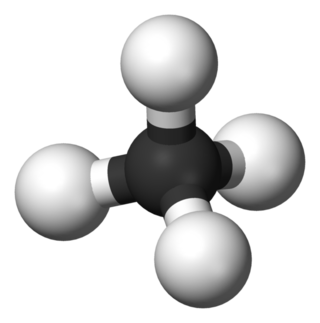

NASA announced in December 2014 that Curiosity had detected sharp increases in methane four times out of twelve during a 20-month period with the Tunable Laser Spectrometer (TLS) of the Sample Analysis at Mars instrument (SAM). Methane levels were ten times greater than usual. Because of the temporary nature of the methane spike, scientists think the source is localized. The source may be biological or non-biological.[65] [66] [67]

File:Methane-3D-balls.png|Methane contains 4 hydrogen atoms and 1 carbon atom covalently bonded to each other. Methane has been detected on Mars, and it could come from living organisms. After two full Martian years (five Earth years) of measurements, researchers found that the annual average concentration of methane in Mars’ atmosphere is 0.41 ppb. However, it must be noted that methane levels rise and fall with the seasons, going from 0.24 ppb in winter to 0.65 ppb in summer. They also observed some relatively large methane spikes, up to about 7 ppb, at random intervals.[68] [69] The existence of methane in the Martian atmosphere is exciting because on Earth, most methane is produced by living organisms. Methane on Mars does not prove that life exists there, but it is consistent with life. Ultraviolet radiation from the sun destroys methane; hence, methane doesn’t last long. To explain its presence something must have been creating or releasing it [70]

Organic Chemicals

Curiosity cannot find and was not designed to find alien life on Mars. But, it has the capacity to look for and identify some organic chemicals. Organic chemicals are associated with life. But one must be aware that a certain amount of organic chemicals are expected on the surface due to the arrival of meteorites over billions of years. Some types of meteorites are loaded with a variety of organic chemicals.

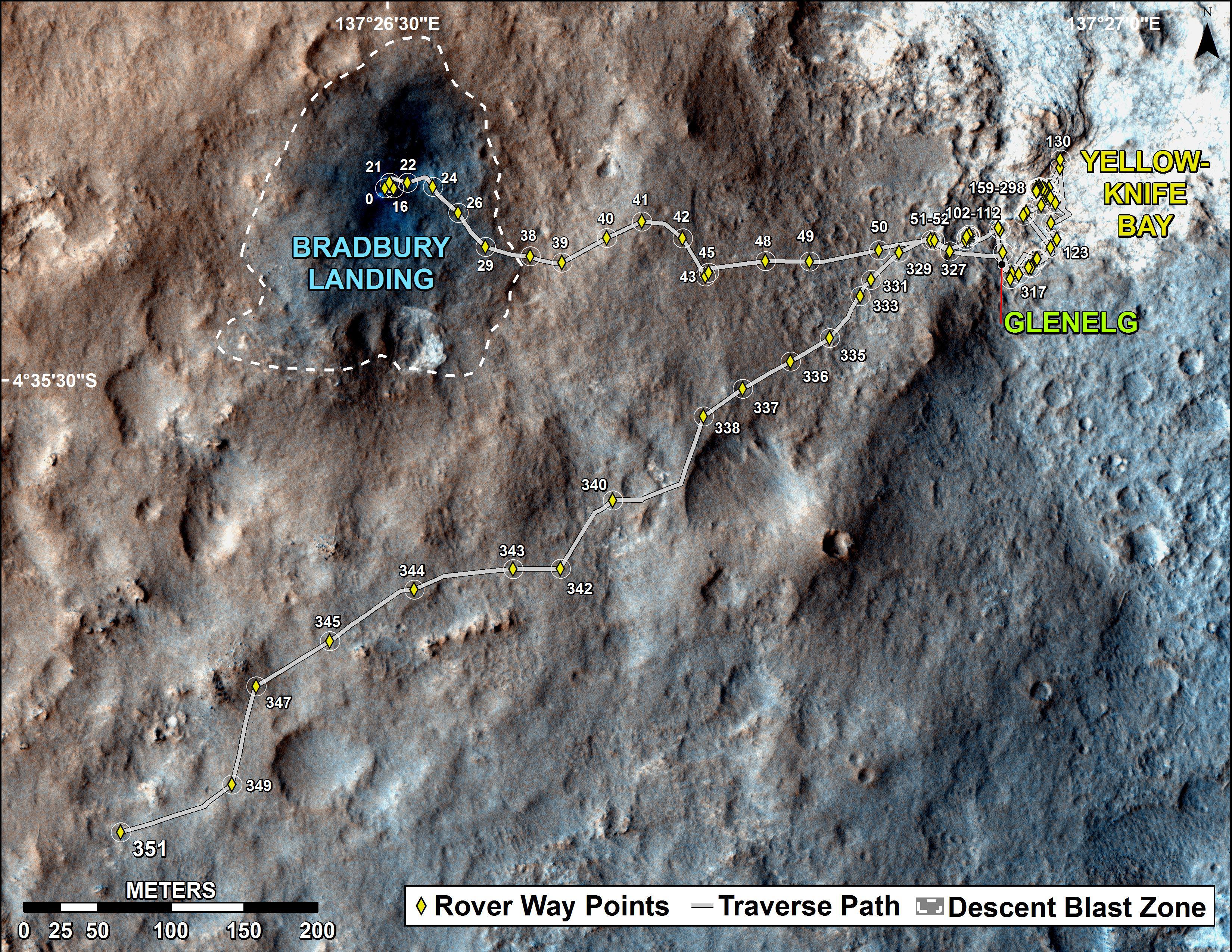

File:PIA17085-MarsCuriosityRover-TraverseMap-Sol351-20130801.jpg|Map showing where Curiosity went in the first year Organic chemicals were found in the Yellow-knife Bay region in Sheepbed mudstone.

The first major testing of the Martian soil yielded interesting results. On December 3, 2012, NASA reported that Curiosity performed its first extensive soil analysis, revealing the presence of water molecules, sulfur and chlorine in the Martian soil. The presence of perchlorates in the sample seems highly likely. The presence of sulfate and sulfide is also likely because sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide were detected. Small amounts of chloromethane, dichloromethane and trichloromethane were detected. The source of the carbon in these molecules is unclear. Possible sources include contamination of the instrument, organics in the sample and inorganic carbonates.[71] [72] Perchlorates, first discovered by the Phoenixmission can complicate the measurement of organic chemicals. Perchlorates may destroy organic chemicals.

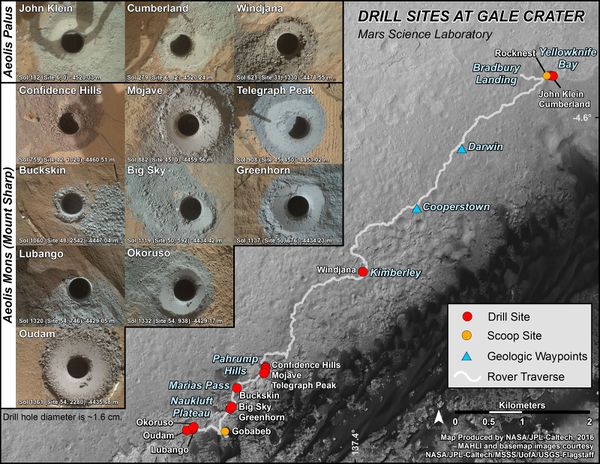

File:7858 mars-curiosity-rover-msl-drill-targets-samples-map-pia20748-full2.jpg|Map showing the first 14 drill sites Some important locations are labeled.

File:PIA17085-MarsCuriosityRover-TraverseMap-Sol351-20130801.jpg|Map showing where Curiosity went in the first year Organic chemicals were found in the Yellow-knife Bay region in Sheepbed mudstone.

The first major testing of the Martian soil yielded interesting results. On December 3, 2012, NASA reported that Curiosity performed its first extensive soil analysis, revealing the presence of water molecules, sulfur and chlorine in the Martian soil. The presence of perchlorates in the sample seems highly likely. The presence of sulfate and sulfide is also likely because sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide were detected. Small amounts of chloromethane, dichloromethane and trichloromethane were detected. The source of the carbon in these molecules is unclear. Possible sources include contamination of the instrument, organics in the sample and inorganic carbonates.[71] [72] Perchlorates, first discovered by the Phoenixmission can complicate the measurement of organic chemicals. Perchlorates may destroy organic chemicals.

File:7858 mars-curiosity-rover-msl-drill-targets-samples-map-pia20748-full2.jpg|Map showing the first 14 drill sites Some important locations are labeled.

In a series of six articles in the journal Science December 9, 2013, teams of NASA researchers described, many new discoveries from the Curiosity rover including possible organics that could not be explained by contamination.[73] [74]

Although the organic carbon was probably from Mars, it can all be explained by dust and meteorites that have landed on the planet.[75] [76]

In a series of six articles in the journal Science December 9, 2013, teams of NASA researchers described, many new discoveries from the Curiosity rover including possible organics that could not be explained by contamination.[73] [74]

Although the organic carbon was probably from Mars, it can all be explained by dust and meteorites that have landed on the planet.[75] [76]

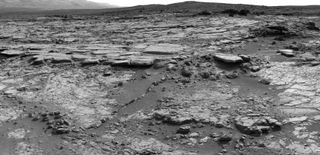

File:5001 pia16564 Sol-133 LNav SnakeRiver-full2yellowknife.jpg|Yellowknife Bay with "Snake River" Sheepbed mudstone which contains organic chemicals is found in this location. “Yellowknife” is a town in Canada. The oldest rocks in North America can be found there.[77]

Because much of the carbon was released at a relatively low temperature in Curiosity’s Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument package, it probably did not come from carbonates in the sample. Carbonates are expected when there is water and carbon dioxide present. Both were probably abundant in the past on Mars. The carbon could be from organisms, but this has not been proven. This organic-bearing matter was obtained by drilling 5 centimeters deep in a site called Yellowknife Bay into a rock called "Snake River." The samples were named”John Klein” and “Cumberland.” Microbes could be living on Mars by obtaining energy from chemical imbalances between minerals in a process called chemolithotrophy which means “eating rock.”Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag </ref>https://www.nasa.gov/content/goddard/mars-organic-matter</ref>

File:PIA17603 Erosion by Scarp Retreat in Gale Crater, Annotated Version.jpg|Location of Sheepbed mudstone where organic chemicals were found. White X is about 43 feet (13 meters) higher in elevation than the Sheepbed-Gillespie contact and at a distance of about 780 feet (240 meters).

At a June 2018 press conference it was announced the detection of more organic molecules in a drill sample analyzed by Curiosity.[78] Some of the organic molecules found were thiophenes, benzene, toluene, and small carbon chains, such as propane or butane.[79] The identity of all the chemicals were not all resolved. At least 50 nanomoles of organic carbon are still in the sample, but were not specifically determined. The remaining organic material probably exists as macromolecules organic sulfur molecules. Organic matter was from lacustrine mudstones at the base of the ~3.5-billion-year-old Murray formation at Pahrump Hills, by the Sample Analysis at Mars instrument suite. [80]

Minerals and Rocks of Mars

With a complex of instruments on Curiosity, we were able to determine a great deal more about the geological make -up and history of Mars. Many, may rocks and soil samples were analyzed by various devices. Basically, we understand Mars as being mostly made of volcanic materials, especially the dark rock basalt which comes out of volcanoes. Mars has many huge volcanoes so this is to be expected. We also found that many of the minerals that weather from basalt. By studying these minerals we can arrive at conclusions about the past conditions that produced them. Many of the minerals were hydrated. That means that water was around. Some of the minerals are clays minerals, clays minerals are significant because not only do they need lots of water to form, but they can’t develop in acid conditions. So, in summary the examinations of rocks/minerals show that Gale Crater contained a lake for a long time with a near neutral ph. It was not acid or basic. The lake had water that could support life. On Earth some organisms have evolved to live in an acid environment, but the vast majority of Earth organisms live in liquids with a near neutral ph. Our stomachs secrete strong hydrochloric acid—not just to digest our foods, but the acid kill things that found there was into our stomachs.[81] Besides basaltic minerals and their weathered products, Curiosity found what are called more evolved rocks. The minerals in these rocks were formed by various processes underground. These are significant because many of our useful mineral ores we use on Earth are from these more evolved minerals. We will understand much more of the history and deep structure of Mars when we receive data from instruments on the InSight mission. It will use a seismometer and a heat probe. It landed in late November 2018 in the Elysium quadrangle. What follows are some of the studies that came from Curiosity’s probes of rocks. On October 17, 2012, at Rocknest (Mars), the first X-ray crystallography and of Martian soil was performed. The outcomes of this test revealed the presence of feldspar, pyroxenes and olivine. Martian soil was like the weathered basaltic soils of Hawaii Volcanoes. The sample was composed of dust distributed from Martian dust storms and local fine sand. So far, the materials Curiosity has analyzed are consistent with the initial ideas of deposits in Gale Crater recording a transition through time from a wet to dry environment.[82]

File:4792 wiens-1pia16192annotated-full2jake.jpg|”Jake Matijevic rock, the first rock analyzed by the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer instrument on Curiosity It is alkaline and relatively fractionated; hence, it is different than most other rocks on Mars. On Earth we get many valuable minerals from fractionated rocks. Marks show where instruments analyzed it. In the journal Science from September 2013, researchers explained a different type of rock called "Jake M (rock)" or "Jake Matijevic (rock),” It was the first rock analyzed by the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer instrument on the Curiosity rover, and was different from other known Martian igneous rocks as it is alkaline (>15% normative nepheline) and relatively fractionated. Jake M is similar to terrestrial mugearites, a rock type typically found at ocean islands and continental rifts. Jake M's discovery may mean that alkaline magmas may be more common on Mars than on Earth and that Curiosity could encounter even more fractionated alkaline rocks (for example, phonolites and trachytes).[83] French and U.S. scientists found a type of granite after studying images and chemical results of 22 rock fragments. The composition of the rocks was resolved with the ChemCam instrument. These pale rocks are rich in feldspar and may contain some quartz. The rocks are similar to Earth's granitic continental crust. On Earth these kinds of rocks form deep underground and are later exposed by erosion. By landing in Gale crater, Curiosity was able to sample a variety of rocks because the crater dug deep into the crust, thus exposing old rocks, some of which may be about 3.6 billion years old. For many years, Mars was thought to be composed of only the dark, igneous rock basalt, so this is a significant discovery.[84] [85] [86] As of 2018, Curiosity's CheMin has discovered discovered olivine, pyroxene, feldspar, quartz, magnetite, iron sulfides (pyrite)and pyrrhotite), akaganeite, jarosite, and calcium sulfates (gypsum, anhydrite, basanite) [87]

Life was possible in Gale Crater

The aim of the Curiosity Rover was not to find alien life, but it was able to find things that could lead us to believe that life may have been possible in Gale Crater [88] Of course, a major case for life would have been to find evidence of past water. Finding out that the water could have a suitable pH is another big plus. Our rover did indeed find evidence for the right kind of water in the past. Various chemicals we think our necessary for life and for the development of life. Curiosity has found many of these as well. Many theories about the origin involve clay minerals. Clay particles are thin and flat; hence, they have a high surface area. Chemicals can attach to clay particles and react with other chemicals that are also stuck on the surface of the clay. Curiosity has found clay. In March 2013, NASA reported Curiosity found evidence that geochemical conditions in Gale Crater were once suitable for microbial life after analyzing the first drilled sample of Martian rock, "John Klein" rock at Yellowknife Bay. The rover detected water, carbon dioxide, oxygen, sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide.[89] [90]

File:5073 pia16726-full2john.jpg|Drill hole that went into rock called “John Klein.” Chemicals detected in this sample showed that this spot was suitable for microbial life.

Chloromethane and dichloromethane were also detected. Related tests found results consistent with the presence of smectite clay minerals.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag [91]

Some samples were probably once mud that for millions to tens of millions of years could have hosted living organisms. This wet environment had neutral pH, low salinity, and variable redox states of both iron and sulfur species.[92] [93] [94] [95]These types of iron and sulfur could have been used by living organisms.[96]

Some clays presented a relative young age (Late Noachian/Early Hesperian or younger age); consequently, in this location neutral pH lasted longer than previously thought. Finding clay minerals is significant because to be created they need a near neutral pH and the water needs to be around for a good length of time.[97]

CheMin found feldspar, mafic igneous minerals, iron oxides, crystalline silica, phyllosilicates, sulfate minerals in mudstone of Gale Crater. Some of the trends in these minerals at different levels suggested that at least part of the time the lake had near-neutral pH.[98] [99] This finding of more evidence that the lake in Gale Crater probably had a neutral pH gives much support to life thriving there.

On March 24, 2015, a paper was released describing the discovery of nitrates in three samples analyzed by Curiosity. The nitrates are believed to have been created from diatomic nitrogen in the atmosphere during meteorite impacts.[100] [101] Nitrogen is necessary for all forms of life because it is used in the building blocks of larger molecules like proteins, DNA, and RNA. Nitrates contain nitrogen in a manner that can be used by living organisms; nitrogen in the air cannot be used by organisms. This discovery of nitrates adds to the evidence that Mars once could have had life.[102] [103]

Researchers in December 2016 announced the discovery of the element boron by Curiosity in mineral veins. For boron to be present there must have been a temperature between 0–60 degrees Celsius and a neutral-to-alkaline pH. The temperature, pH, and dissolved minerals of the groundwater support a habitable environment. So, boron is a marker for an environment conducive for life[104]

Of great significance is that boron has been suggested to be necessary for life to form. Its presence stabilizes the sugar ribose which is an ingredient in RNA.[105] [106] [107] Specifics of the discovery of Boron on Mars were described in a paper written by a large number of researchers and published in Geophysical Research Letters.[108] [109] [110] [111]

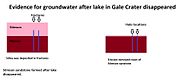

By 2018, researchers had concluded that Gale Crater has experienced many episodes of groundwater. As this was going on the chemistry of the groundwater changed. These chemical changes were the kind that would support life.[112] [113] [114] [115]

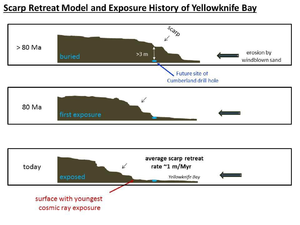

Fractures that went through both Murray mudstone and Stimson sandstone layers had silica deposited in them (shown in left drawing). After erosion removed most of Stimson layer, halos were found around the fractures by the Curiosity Rover. Because the Stimson was formed after the lake disappeared, water must have been in the ground for a long time after the lake dried up.

Meteorites

Using date gathered with Mastcam, a team of researchers found what they believe to be iron meteorites. These meteorites stand out in multispectral observations as not having the usual ferrous or ferric absorption features as the surrounding surface.[118] One would expect to find many meteorites on the Martian surface because of billions of years of bombardment by asteroids of various sizes. Both the Spirit and Opportunity rovers on Mars found meteorites.[119] [120] [121] [122] [123] [124] Meteoritic material may be very important for future colonists on the Red Planet. We may invent robotic machines to go out and collect and process iron meteorites.

Astronomy Observations

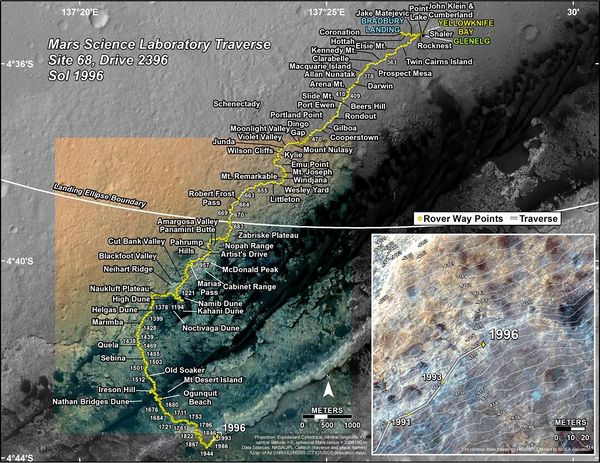

File:MSL TraverseMap Sol1996-br2.jpg|Journey of Curiosity through March 22, 2018 Numbering of the dots along the line indicate the sol number of each drive. A sol is a Martian day—a little longer than an Earth day.

File:MSL TraverseMap Sol1996-br2.jpg|Journey of Curiosity through March 22, 2018 Numbering of the dots along the line indicate the sol number of each drive. A sol is a Martian day—a little longer than an Earth day.

Regolith for greenhouses

The Martian regolith resembles basaltic soil from Hawaii.[125]

Conclusion: The regolith is a good base for making soil for greenhouses in the Martian colony.

Future

Since Curiosity is powered by radioactive isotopes, rather than solar panels, it may be exploring Mars for many, many years. About the only major potential problem in sight are the wheels. Fairly early on in the mission, it was noticed that the wheels had been punctured by sharp rocks. When driving over certain surfaces, Curiosity’s wheels were being pierced by sharp rocks sticking up. These rocks from hell were probably part of the underlying rock formation; as such they did not give when the one ton rover passed over them. [126] The wheels have parts that are very thin—those are the ones being affected by sharp rocks. Stills, the people in charge of driving the rover are being very careful.

References

- ↑ https://mars.nasa.gov/msl/mission/timeline/launch/

- ↑ https://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/watch-curiosity-descend-onto-mars/

- ↑ https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/missions/curiosity-msl/in-depth/

- ↑ Pyle, R. 2014. Curiosity. Prometheus Books. Amherst, N.Y.

- ↑ https://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/mount-sharp-or-aeolis-mons/

- ↑ Pyle, R. 2014. Curiosity. Prometheus Books. Amherst, N.Y.

- ↑ https://mars.nasa.gov/resources/4494/the-heights-of-mount-sharp/

- ↑ Pyle, R. 2014. Curiosity. Prometheus Books. Amherst, N.Y.

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/press_kits/MSLLaunch.pdf

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curiosity_%28rover%29

- ↑ https://mars.nasa.gov/msl/mission/technology/insituexploration/edl/skycrane/

- ↑ Pyle, R. 2014. Curiosity. Prometheus Books. Amherst, N.Y.

- ↑ https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/missions/curiosity-msl/in-depth/

- ↑ Goudge, T., et al. 2017. STRATIGRAPHY AND EVOLUTION OF DELTA CHANNEL DEPOSITS, JEZERO CRATER, MARS. Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017). 1195.pdf.

- ↑ Baker, V. 1982. The Channels of Mars. Univ. of Tex. Press, Austin, TX

- ↑ Baker, V., R. Strom, R., V. Gulick, J. Kargel, G. Komatsu, V. Kale. 1991. Ancient oceans, ice sheets and the hydrological cycle on Mars. Nature 352, 589–594.

- ↑ Goudge, T., K. Aureli, J. Head, C. Fassett, J. Mustard. 2015. Classification and analysis of candidate impact crater-hosted closed-basin lakes on Mars. Icarus: 260, 346-367.

- ↑ Fassett, C. J. Head. 2008. Valley network-fed, open-basin lakes on Mars: Distribution and implications for Noachian surface and subsurface hydrology. Icarus: 198, 37-56.

- ↑ Gaetano Di Achille, Brian M. Hynek. Ancient ocean on Mars supported by global distribution of deltas and valleys. Nature, 2010; DOI: 10.1038/ngeo891

- ↑ Head et al. 1999. Possible Ancient oceans on Mars: Evidence from mars orbiter laser Altimeter Data. Science 286, 2134.

- ↑ Carr,M. 1996. Water on Mars. Oxford.

- ↑ Parker, T.J., Saunders, R.S., and Schneeberger, D.M., 1989, Transitional morphology in the west Deuteronilus Mensae region of Mars: Implications for modification of the lowland/upland boundary: Icarus , v. 82, 111–145, doi:10.1016/0019-1035(89)90027-4.

- ↑ Parker, T., et al. 1993. Coastal geomorphology of the Martian northern plains. Journal of Geophysical Research. 98. 11061.

- ↑ Carr, M. , J. Head. 2003. Oceans of Mars: An assessment of the observational evidence and possible fate. Journal of Geophysical Research. 108(E5). 5041. Doi:10.1029/2002JE001963, 2003.

- ↑ Carr, M. , J. Head. 2003. Oceans of Mars: An assessment of the observational evidence and possible fate. Journal of Geophysical Research. 108(E5). 5041. Doi:10.1029/2002JE001963, 2003.

- ↑ https://www.space.com/6394-phoenix-mars-lander-liquid-water-scientists.html

- ↑ https://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/drops-of-water-on-mars/

- ↑ https://www.astrobio.net/mars/liquid-water-ice-salt-mars/

- ↑ Smith, P., et al. 2009. H2O at the Phoenix Landing Site. Science: 325, 58-61.

- ↑ https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/phoenix/news/phoenix-20080530.html

- ↑ https://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2012/sep/HQ_12-338_Mars_Water_Stream.html

- ↑ Chang, Alicia (September 27, 2012). "Mars rover Curiosity finds signs of ancient stream". Associated Press. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ↑ Williams, R. M. E.; Grotzinger, J. P.; Dietrich, W. E.; Gupta, S.; Sumner, D. Y.; Wiens, R. C.; Mangold, N.; Malin, M. C.; Edgett, K. S.; Maurice, S.; Forni, O.; Gasnault, O.; Ollila, A.; Newsom, H. E.; Dromart, G.; Palucis, M. C.; Yingst, R. A.; Anderson, R. B.; Herkenhoff, K. E.; Le Mouelic, S.; Goetz, W.; Madsen, M. B.; Koefoed, A.; Jensen, J. K.; Bridges, J. C.; Schwenzer, S. P.; Lewis, K. W.; Stack, K. M.; Rubin, D.; et al. (2013-07-25). "Martian fluvial conglomerates at Gale Crater". Science. 340 (6136): 1068–1072.

- ↑ Williams R.; et al. (2013). "Martian fluvial conglomerates at Gale Crater". Science. 340 (6136): 1068–1072.

- ↑ https://www.nasa.gov/press/2014/december/nasa-s-curiosity-rover-finds-clues-to-how-water-helped-shape-martian-landscape

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/09/science/-stronger-signs-of-life-on-mars.html

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/video/details.php?id=1346

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=4398

- ↑ http://astrobiology.com/2015/10/wet-paleoclimate-of-mars-revealed-by-ancient-lakes-at-gale-crater.html

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=4734

- ↑ Grotzinger, J.P.; et al. (October 9, 2015). "Deposition, exhumation, and paleoclimate of an ancient lake deposit, Gale crater, Mars". Science: 350 (6257): aac7575.

- ↑ https://phys.org/news/2018-11-evidence-outburst-plentiful-early-mars.html

- ↑ Significance of Flood Deposits in Gale Crater, Mars. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. Vol. 50, No. 6 DOI: 10.1130/abs/2018AM-319960, https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2018AM/webprogram/Paper319960.html

- ↑ https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/11/181105132920.htm

- ↑ https://mars.nasa.gov/resources/7056/prominent-veins-at-garden-city-on-mount-sharp-mars/

- ↑ https://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/msl/news/whatsnew/index.cfm?FuseAction=ShowNews&NewsID=1446

- ↑ https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-21340279

- ↑ Lin H.; et al. (2016). "Abundance retrieval of hydrous minerals around the Mars Science Laboratory landing site in Gale crater, Mars". Planetary and Space Science. 121: 76–82.

- ↑ NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "NASA rover findings point to a more Earth-like Martian past." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 27 June 2016. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/06/160627125731.htm>.

- ↑ Lanza, Nina L.; Wiens, Roger C.; Arvidson, Raymond E.; Clark, Benton C.; Fischer, Woodward W.; Gellert, Ralf; Grotzinger, John P.; Hurowitz, Joel A.; McLennan, Scott M.; Morris, Richard V.; Rice, Melissa S.; Bell, James F.; Berger, Jeffrey A.; Blaney, Diana L.; Bridges, Nathan T.; Calef, Fred; Campbell, John L.; Clegg, Samuel M.; Cousin, Agnes; Edgett, Kenneth S.; Fabre, Cécile; Fisk, Martin R.; Forni, Olivier; Frydenvang, Jens; Hardy, Keian R.; Hardgrove, Craig; Johnson, Jeffrey R.; Lasue, Jeremie; Le Mouélic, Stéphane; Malin, Michael C.; Mangold, Nicolas; Martìn-Torres, Javier; Maurice, Sylvestre; McBride, Marie J.; Ming, Douglas W.; Newsom, Horton E.; Ollila, Ann M.; Sautter, Violaine; Schröder, Susanne; Thompson, Lucy M.; Treiman, Allan H.; VanBommel, Scott; Vaniman, David T.; Zorzano, Marìa-Paz (2016). "Oxidation of manganese in an ancient aquifer, Kimberley formation, Gale crater, Mars". Geophysical Research Letters. 43 (14): 7398–7407.

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=6544

- ↑ Schwenzer, S. P.; Bridges, J. C.; Wiens, R. C.; Conrad, P. G.; Kelley, S. P.; Leveille, R.; Mangold, N.; Martín-Torres, J.; McAdam, A.; Newsom, H.; Zorzano, M. P.; Rapin, W.; Spray, J.; Treiman, A. H.; Westall, F.; Fairén, A. G.; Meslin, P.-Y. (2016). "Fluids during diagenesis and sulfate vein formation in sediments at Gale crater, Mars". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 51 (11): 2175–202.

- ↑ https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/08/160805085749.htm

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/spaceimages/details.php?id=pia21263

- ↑ http://spaceref.com/mars/desiccation-cracks-reveal-the-shape-of-water-on-mars.html

- ↑ Stein, N.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Schieber, J.; Mangold, N.; Hallet, B.; Newsom, H.; Stack, K.M.; Berger, J.A.; Thompson, L.; Siebach, K.L.; Cousin, A.; Le Mouélic, S.; Minitti, M.; Sumner, D.Y.; Fedo, C.; House, C.H.; Gupta, S.; Vasavada, A.R.; Gellert, R.; Wiens, R. C.; Frydenvang, J.; Forni, O.; Meslin, P. Y.; Payré, V.; Dehouck, E. (2018). "Desiccation cracks provide evidence of lake drying on Mars, Sutton Island member, Murray formation, Gale Crater". Geology. 46 (6): 515–518.

- ↑ https://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/msl/news/whatsnew/index.cfm?FuseAction=ShowNews&NewsID=1446

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=4549

- ↑ University of Copenhagen – Niels Bohr Institute. "Mars might have salty liquid water." ScienceDaily. 13 April 2015. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/04/150413130611.htm>.

- ↑ https://www.space.com/29072-mars-liquid-water-at-night.html

- ↑ Martin-Torre, F. et al. 2015. Transient liquid water and water activity at Gale crater on Mars. Nature geoscienceDOI:10.1038/NGEO2412

- ↑ Mars is safe from radiation – but the trip there isn't

- ↑ http://certificate.ulo.ucl.ac.uk/modules/year_one/NASA_GSFC/goddard/imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/science/know_l2/cosmic_rays.html

- ↑ https://home.cern/science/accelerators/large-hadron-collider

- ↑ https://www.nasa.gov/press/2014/december/nasa-rover-finds-active-ancient-organic-chemistry-on-mars

- ↑ Webster1, C. et al. 2014. Mars methane detection and variability at Gale crate. Science. 1261713

- ↑ https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/Mars-Rover-Curiosity-Methane-285996081.html

- ↑ https://www.sciencenews.org/article/curiosity-finds-mars-methane-changes-seasons

- ↑ Webster, C., et al. Background levels of methane in Mars’ atmosphere show strong seasonal variations. Science: 360, June 8, 2018, p. 1093. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0131.

- ↑ Webster, C., et al. Background levels of methane in Mars’ atmosphere show strong seasonal variations. Science: 360, June 8, 2018, p. 1093. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0131.

- ↑ https://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/msl/news/whatsnew/index.cfm?FuseAction=ShowNews&NewsID=1399

- ↑ https://thelede.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/03/mars-rover-discovery-revealed

- ↑ Blake, D.; et al. (2013). "Curiosity at Gale crater, Mars: characterization and analysis of the Rocknest sand shadow – Medline" (PDF). Science (Submitted manuscript). 341 (6153): 1239505.

- ↑ Leshin, L.; et al. (2013). "Volatile, isotope, and organic analysis of martian fines with the Mars Curiosity rover - Medline". Science. 341 (6153): 1238937.

- ↑ McLennan, M.; et al. (2013). "Elemental geochemistry of sedimentary rocks at Yellowknife Bay, Gale Crater, Mars" (PDF). Science (Submitted manuscript). 343 (6169): 1244734.

- ↑ Flynn, G. (1996). "The delivery of organic matter from asteroids and comets to the early surface of Mars". Earth Moon Planets. 72 (1–3): 469–474.

- ↑ Pyle, R. 2014. Curiosity. Prometheus Books. Amherst, N.Y.

- ↑ Eigenbrode, J., et al. Organic matter preserved in 3-billion-year-old mudstones at Gale crater, Mars. Science: 360, June 8, 2018, p. 1096. doi:10.1126/science.aas9185.

- ↑ http://astrobiology.com/2018/06/curiosity-finds-ancient-organic-compounds-that-match-meteoritic-samples.html

- ↑ Eigenbrode, Jennifer L.; Summons, Roger E.; Steele, Andrew; Freissinet, Caroline; Millan, Maëva; Navarro-González, Rafael; Sutter, Brad; McAdam, Amy C.; Franz, Heather B.; Glavin, Daniel P.; Archer, Paul D.; Mahaffy, Paul R.; Conrad, Pamela G.; Hurowitz, Joel A.; Grotzinger, John P.; Gupta, Sanjeev; Ming, Doug W.; Sumner, Dawn Y.; Szopa, Cyril; Malespin, Charles; Buch, Arnaud; Coll, Patrice (2018). "Organic matter preserved in 3-billion-year-old mudstones at Gale crater, Mars". Science: (6393): 1096–1101.

- ↑ https://www.livestrong.com/article/419261-role-of-hydrochloric-acid-in-the-stomach/

- ↑ https://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2012/oct/HQ_12-383_Curiosity_CheMin.html

- ↑ Stolper, E.; et al. (2013). "The Petrochemistry of Jake M: A Martian Mugearite" (PDF). Science (Submitted manuscript). 341 (6153): 6153. https://authors.library.caltech.edu/41547/

- ↑ http://spaceref.com/mars/evidence-of-mars-primitive-continental-crust.html

- ↑ https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/07/150714142051.htm

- ↑ Sautter, V.; Toplis, M.; Wiens, R.; Cousin, A.; Fabre, C.; Gasnault, O.; Maurice, S.; Forni, O.; Lasue, J.; Ollila, A.; Bridges, J.; Mangold, N.; Le Mouélic, S.; Fisk, M.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Beck, P.; Pinet, P.; Le Deit, L.; Rapin, W.; Stolper, E.; Newsom, H.; Dyar, D.; Lanza, N.; Vaniman, D.; Clegg, S.; Wray, J. (2015). "In situ evidence for continental crust on early Mars" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 8 (8): 605–609.

- ↑ Lakdawalla, E. 2018. The Design and Engineering of Curiosity: How the Mars Rover Performs its job. Springer Praxis Publishing. Chichester, UK

- ↑ https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/missions/curiosity-msl/in-depth/

- ↑ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2013-092

- ↑ https://www.space.com/20187-ancient-mars-life-curiosity-faq.html

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/13/science/space/mars-could-have-supported-life-nasa-says.html

- ↑ McLennan, M.; et al. (2013). "Elemental geochemistry of sedimentary rocks at Yellowknife Bay, Gale Crater, Mars" (PDF). Science (Submitted manuscript). 343 (6169): 1244734.

- ↑ Vaniman, D.; et al. (2013). "Mineralogy of a mudstone at Yellowknife Bay, Gale crater, Mars" (PDF). Science. 343 (6169): 1243480.

- ↑ Bibring, J.; et al. (2006). "Global mineralogical and aqueous mars history derived from OMEGA/Mars Express data". Science. 312 (5772): 400–404.

- ↑ Squyres, S.; A. Knoll. (2005). "Sedimentary rocks and Meridiani Planum: Origin, diagenesis, and implications for life of Mars". Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 240 (1): 1–10.

- ↑ Nealson, K.; P. Conrad. (1999). "Life: past, present and future". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 354: 1923–1939.

- ↑ Vaniman, D.; et al. (2013). "Mineralogy of a mudstone at Yellowknife Bay, Gale crater, Mars" (PDF). Science. 343 (6169): 1243480.

- ↑ Bristow T. F. et al. 2015 Am. Min., 100.

- ↑ Rampe, E., et al. 2017. MINERAL TRENDS IN EARLY HESPERIAN LACUSTRINE MUDSTONE AT GALE CRATER, MARS. Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017). 2821pdf

- ↑ https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/03/150325082341.htm

- ↑ Stern, J.; Sutter, B.; Freissinet, C.; Navarro-González, R.; McKay, C.; Archer, P.; Buch, A.; Brunner, A.; Coll, P.; Eigenbrode, J.; Fairen, A.; Franz, H.; Glavin, D.; Kashyap, S.; McAdam, A.; Ming, D.; Steele, A.; Szopa, C.; Wray, J.; Martín-Torres, F.; Zorzano, Maria-Paz; Conrad, P.; Mahaffy, P. (2015). "Evidence for indigenous nitrogen in sedimentary and aeolian deposits from the Curiosity rover investigations at Gale crater, Mars". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (14): 4245–4250.

- ↑ http://astrobiology.com/2015/03/curiosity-rover-finds-biologically-useful-nitrogen-on-mars.html

- ↑ https://www.space.com/28899-mars-life-nitrogen-carbon-monoxide.html?adbid=10152715032851466&adbpl=fb&adbpr=17610706465

- ↑ http://spaceref.com/mars/first-detection-of-boron-on-the-surface-of-mars.html

- ↑ http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2013PLoSO...864624S

- ↑ Kim HJ, Benner SA (2010). ""Comment on "The silicate-mediated formose reaction: bottom-up synthesis of sugar silicates". Science. 20 (329): 5994.

- ↑ Ricardo, A.; Carrigan, M.A.; Olcott, A.N.; Benner, S.A. (2004). "Borate minerals stabilize ribose". Science. 303 (5655): 196.

- ↑ Gasda, P., et al. 2017. In situ detection of boron by ChemCam on Mars. Geophysical Research Letters. DOI: 10.1002/2017GL074480

- ↑ https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-4855658/Breakthrough-hunt-life-Mars.html

- ↑ https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/09/170905123226.htm

- ↑ Gasda, Patrick J.; Haldeman, Ethan B.; Wiens, Roger C.; Rapin, William; Bristow, Thomas F.; Bridges, John C.; Schwenzer, Susanne P.; Clark, Benton; Herkenhoff, Kenneth; Frydenvang, Jens; Lanza, Nina L.; Maurice, Sylvestre; Clegg, Samuel; Delapp, Dorothea M.; Sanford, Veronica L.; Bodine, Madeleine R.; McInroy, Rhonda (2017). "In situ detection of boron by ChemCam on Mars". Geophysical Research Letters. 44 (17): 8739–8748.

- ↑ Schwenzer, S. P.; et al. (2016). "Fluids during diagenesis and sulfate vein formation in sediments at Gale Crater, Mars". Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 51 (11): 2175–2202.

- ↑ L'Haridon, J., N. Mangold, W. Rapin, O. Forni, P.-Y. Meslin, E. Dehouck, M. Nachon, L. Le Deit, O. Gasnault, S. Maurice, R. Wiens. 2017. Identification and implications of iron detection within calcium sulfate mineralized veins by ChemCam at Gale crater, Mars, paper presented at 48th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, The Woodlands, Tex., Abstract 1328.

- ↑ Lanza, N. L.; et al. (2016). "Oxidation of manganese in an ancient aquifer, Kimberley formation, Gale crater". Geophys. Res. Lett. 43 (14): 7398–7407.

- ↑ Yen, A. S.; et al. (2017). "Multiple stages of aqueous alteration along fractures in mudstone and sandstone strata in Gale Crater, Mars". Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 471: 186–198.

- ↑ https://www.lanl.gov/discover/news-release-archive/2017/May/0530-halos-discovered-on-mars.php?source=newsroom

- ↑ https://mars.nasa.gov/news/high-silica-halos-shed-light-on-wet-ancient-mars/

- ↑ Wellington, D., et al. 2018. IRON METEORITE CANDIDATES WITHIN GALE CRATER, MARS, FROM MSL/MASTCAM MULTISPECTRAL OBSERVATIONS. 49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2083). 1832.pdf

- ↑ Schröder C. et al. 2008. JGR, 113, E06S22, 10.1029/2007JE002990

- ↑ Ashley J. W. 2009. LPS XL, Abstract #2468.

- ↑ Ashley J. W. 2011. JGR, 116, E00F20, 10.1029/2010JE003672

- ↑ Arvidson R. E. et al. 2011. JGR, 116, E00F15, 10.1029/2010JE003746.

- ↑ Meslin P.-Y. et al. 2017. LPS XLVII, Abstract #2258

- ↑ Ashley J. W. and Herkenhoff K. E. 2017. LPS XLVII, Abstract #2656

- ↑ NASA Rover's First Soil Studies Help Fingerprint Martian Minerals

- ↑ Pyle, R. 2014. Curiosity. Prometheus Books. Amherst, N.Y.

See Also

Recommended reading

Grotzinger, J., R. Milliken (eds.). 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. Tulsa: Society for Sedimentary Geology. Lakdawalla, E. 2018. The Design and Engineering of Curiosity: How the Mars Rover Performs its job. Springer Praxis Publishing. Chichester, UK </ref> Pyle, R. 2014. Curiosity. Prometheus Books. Amherst, N.Y.

External links

- [ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LAL4F6IWC-Y Full Video of Curiosity Landing on Mars]

- [ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zqhK8dA7iO8 Five Years of Curiosity on Mars (public talk)]

- [ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Z9zgMOjdPE The Curiosity Rover's Most Amazing Discoveries]

- [ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/press_kits/MSLLanding.pdf Press kit for Curiosity]

- [ https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/press_kits/MSLLaunch.pdf Press Kit for Mars Science Laboratory launch]